Then and Now: Masonic Landmarks of San Francisco

Four San Francisco Masonic landmarks of yesteryear get a new lease on life.

By Ian A. Stewart

Masons have met in San Francisco since at least 1848, when the first formal meeting of what would become San Francisco № 1 gathered together to launch their group. Since then, Masonry spread throughout the city, reaching its zenith in the middle of the 20th century, when 42 lodges met in practically every corner of the seven-mile by seven-mile city. And while the Grand Lodge temple (first at Post and Montgomery, later at 25 Van Ness, and now at 1111 California Street) has always been the fraternity’s headquarters, Masonic San Francisco stretched from the bay to the ocean, from the Richmond to the Mission, from FiDi to the Avenues.

Here, we’re charting some of the most interesting, notable, or overlooked Masonic meeting places in San Francisco history.

Visit freemason.org for an interactive map of these Masonic landmarks.

The Genella Building was the site of the first official meeting of California № 13 (later to become California № 1) under master Levi Stowell, who carried the charter from Washington, D.C. to California. The lodge held its first meeting there Nov. 15, 1848 with eight members present and 37 visitors, but it didn’t stay long: By 1850, it had moved into a new hall on Kearny Street, the second of six meeting places in its first century, and then in 1852 to another location on Washington Street (see below, No. 2). A plaque commemorating the site was once affixed to the brick building on Montgomery, but was removed in recent years.

The third meeting place of California № 1, this was another short-lived home, a two-story brick building on the south side of Washington that also served as a theater, in the shadow of where the Transamerica Pyramid is today. By 1853, the lodge was meeting at the “New” Masonic Temple on Montgomery Street (see below). San Francisco № 7, Occidental № 22, and La Parfaite Union № 17 also met on Washington Street in 1852–53, along with San Francisco Chapter № 1 of the Royal Arch, and the Annual Communication was held there in 1852 and 1855.

Completed in July 1853, this four-story hall was owned by Samuel Brannan, one of the most colorful characters in San Francisco history. Brannan originally landed in California on a mission to launch a Mormon colony but soon broke with the church, founded a newspaper, opened a mining store, and, through several real estate deals, became the richest man in San Francisco. Ironically, Brannan petitioned Occidental № 22 for membership in 1855 but was denied. He later received his degrees in New York and was only accepted into the lodge that he’d once been landlord of in 1858. The hall, which also housed Golden Gate № 30 and Mt. Moriah № 44, was largely abandoned in the 1860s, when the Grand Lodge temple at Post and Montgomery was opened.

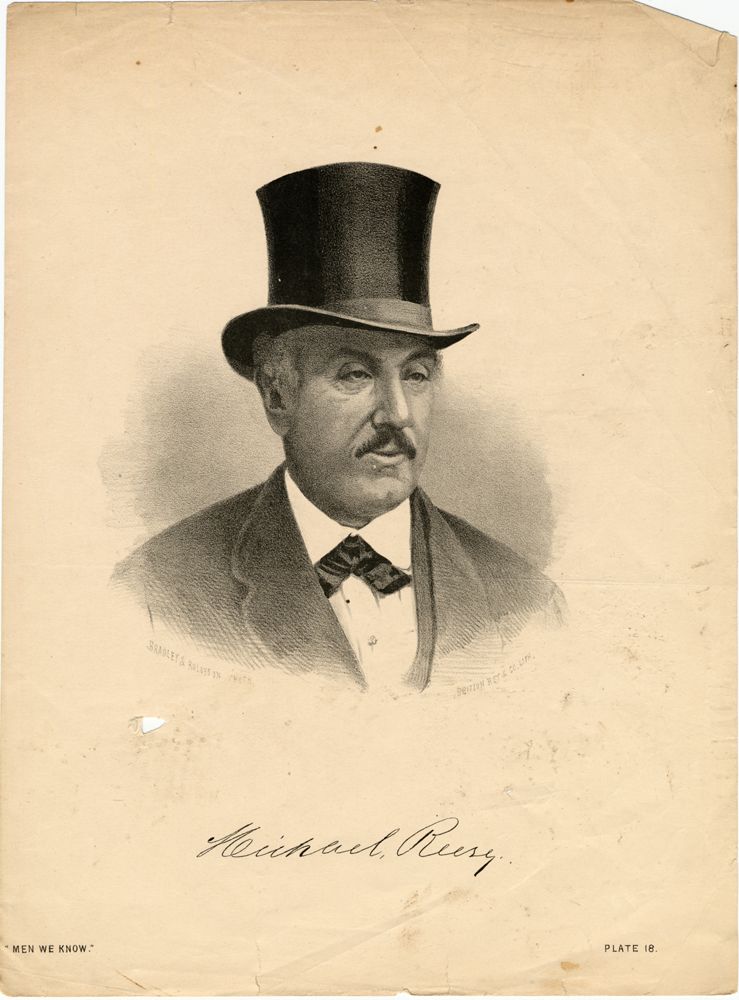

The Masonic hall on the third floor of the brick structure known as Reese’s Building (owned by the millionaire mining magnate and real estate tycoon Michael Reese), at the corner of Portsmouth Square, was in 1861 home to several lodges including La Parfaite Union № 17, Golden Gate № 30, Mt. Moriah № 49, Fidelity № 120, and Oriental № 144—the latter of which split from Occidental № 22 in 1860 at the dawn of the Civil War, the result of an intralodge dispute pitting northerners (who affiliated with Oriental) against their Southern lodge brothers.

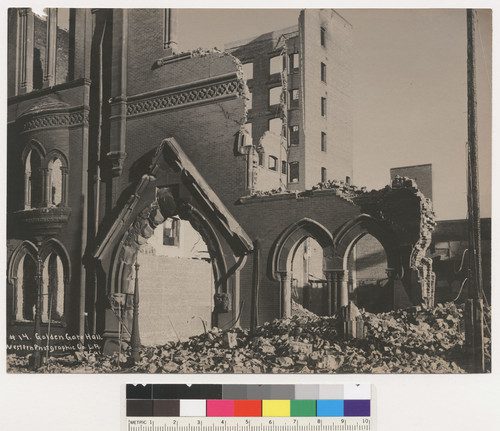

Construction on the first permanent home for the Grand Lodge, at Post and Montgomery, began in 1860 and was finished in 1870 for about $250,000 (approximately $6 million today). More than 1,000 Masons gathered for its ceremonial cornerstone-laying, marching from Portsmouth Square to the site of the new temple, designed by architects Reuben Clark (of Mount Moriah № 44) and Henry Kenitzer (of Fidelity № 120). The three-story Italian-Gothic structure, which served 10 blue lodges and virtually all the other Masonic bodies in the city, was crowned by a 128-foot tower above Montgomery Street. Grand Master William Belcher in 1863 declared: “This is the finest and most perfect building upon the Pacific coast.” However, by the time it was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, both the city and fraternity had outgrown it: During its lifespan, the fraternity had grown from 6,000 members in San Francisco to more than 33,000.

Another early and relatively short-lived meeting place, this belonged to Golden Gate Commandery № 16 of the Knights Templar, one of two early commanderies in the city (along with California № 1; a third, San Francisco № 41, came later). The group first met in 1881 at the Grand Lodge temple at Post and Montgomery streets, and later moved into the “Golden Gate Block” building at 131 Post Street. In 1891, Golden Gate № 16 raised $130,000 to construct the new temple, and the San Francisco City Directory first lists it meeting there in 1896. However, by 1904, the group was once again on the move, eventually relocating to 2135 Sutter (see below, No. 14), where it remained until the 1970s. The Golden Gate Hall, which was also used as a theater, hosted several blue lodges, including California № 1, Mt. Moriah № 44, Doric № 216, and Jewel № 374. It was destroyed in 1906.

When in 1888 the members of South San Francisco № 212 dedicated the cornerstone for their new lodge on Third Street (then Railroad Avenue), in what’s now called the Bayview, the neighborhood was known as Butchertown—an apt name for what was then a motley assortment of farms and slaughterhouses. So it might have registered as curious the decision to erect, immediately adjacent to the new hall, an elaborate Italianate-style opera hall designed by Henry Geilfuss, one of the most prolific architects of the era. During the late 19th century, the remote opera hall became a major cultural institution, with barnstorming theater companies often bringing touring shows to the Bayview in advance of dates downtown. Following the 1906 earthquake, however, the theater’s fortunes began to fade, and the structure fell into disrepair. The lodge eventually sold the building in 1965 and consolidated into Francis Drake-South San Francisco № 212. In recent years, the opera house has undergone a significant renovation and today hosts several community groups and theater companies, though the old lodge room no longer remains.

The 38-acre gravesite on Lone Mountain—one of the “Big Four” cemeteries at what’s now the University of San Francisco—once served 20,000 souls. The entrance to the 1880s park was marked by a large castellated tomb; other decorations included a white marble obelisk topped by a statue of Grief and other monuments. “The broad, serpentine walks, the fountain playing in the center, the profusion of flowers, and the large number of handsome monuments make it well worth a visit,” according to an 1887 guidebook. Among its notable headstones were prominent San Francisco Masons including the sugar king Adolph B. Spreckles and Munroe Ashbury, an early champion of Golden Gate Park. In the wake of the 1906 earthquake, the cemetery was shuttered, part of a citywide effort to re-inter San Francisco’s dead elsewhere. However, its legacy remains: It’s estimated that only a quarter of its dead were ever moved.

For several years before and after the 1906 earthquake and fire, a number of Masonic lodges shared space with the Jewish fraternal organization B’nai B’rith in their lodge hall in the Tenderloin. Among those groups were Pacific № 136, Crockett № 139, and Doric № 216, and, in the 1920s and beyond, Military Service № 570, Bethlehem № 453, Lincoln № 470, Roosevelt № 500, and Fairmont № 435.

The Palace Hotel is one of the most august institutions in downtown San Francisco, tracing its history to 1875, when it was considered not just the greatest hotel in San Francisco, but in the West. It also has a close connection to Freemasonry: In 1916, the fraternity opened the Masonic Club of San Francisco inside the hotel, taking over the entire west wing of the second floor of the building. Inside were eight rooms practically dripping in luxury, plus a dining room, billiards room, and card room, all in addition to the main clubhouse. The hotel also reserved several hotel rooms for Masonic Club members and their guests. Its initial membership numbered 1,700, including bold-faced names like William H. Crocker, son of the Southern Pacific Railroad fortune. The club was born out of Bethlehem № 453, and during World War I, it helped organize the Masonic Ambulance Corps, a volunteer company that deployed to the Argonne.

In the late 19th century, as Masonry was taking off in San Francisco, business unsurprisingly followed. Beginning in the 1860s, several Masonic goods retailers popped up downtown offering lodge furnishings, Masonic regalia, costumes, and more. One of the largest of these was Daniel Norcross Masonic Goods, relocated from Sacramento Street to the Grand Lodge temple at 6 Post Street. Norcross was a member of Oriental № 144. He certainly wasn’t the only one in the business: The Johnson T. Rogers Masonic Goods Co. set up stakes in the 1860s, while AJ Plate and Co. Masonic Goods hawked its wares from 325 Montgomery. CF Weber and Co. came in the 1910s, while a West Coast outpost of the Henderson-Ames Lodge Paraphernalia Co. formed in 1920 at 833 Market Street. In the 1940s, ABC Emblem & Pennant Co. at 1251 Market Street was similarly advertising Masonic regalia.

Though he lived in San Francisco for just four years, Rev. Thomas Starr King left an indelible mark on the state and is remembered as the man who “saved California for the Union” during the Civil War. A preacher at First Unitarian Church, he earned fame for his speeches against slavery. He helped raise massive sums for the predecessor of today’s Red Cross, and upon his death at age 39, thousands came to his funeral. Fittingly, Starr King, who joined Oriental № 144 in 1861, served as Grand Orator for the Grand Lodge of California in 1864, the year he died. In 1892, a memorial fund was raised to erect a statue of him by Daniel Chester French (designer of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.) in Golden Gate Park. More than 2,000 people attended the opening, including King’s grandsons. Across town, his grave is marked by a marble sarcophagus outside the church he served, which is now on a small street named Starr King Place near Franklin Street.

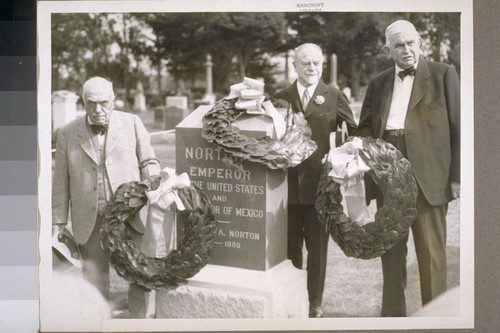

San Francisco’s most celebrated 19th century eccentric, Joshua Norton was a failed businessman turned beloved prophet. He roamed the streets in a faded military costume and proclaimed himself Emperor Norton I, penning missives proposing, among other things, a bridge connecting San Francisco to Oakland and an underwater streetcar tube traversing the bay—a century before those came into being. A member of Occidental № 22, Norton died penniless, but today is remembered as a hero. In 2023, the 600 block of Commercial Street (between Montgomery and Kearny) was renamed in his honor. Norton lived at the Eureka Lodgings at 624 Commercial Street from 1864 or 1865 until his death in 1880. That building was destroyed in 1906; a four-story building constructed on the same site in 1910 remains there at 650-654 Commercial Street.

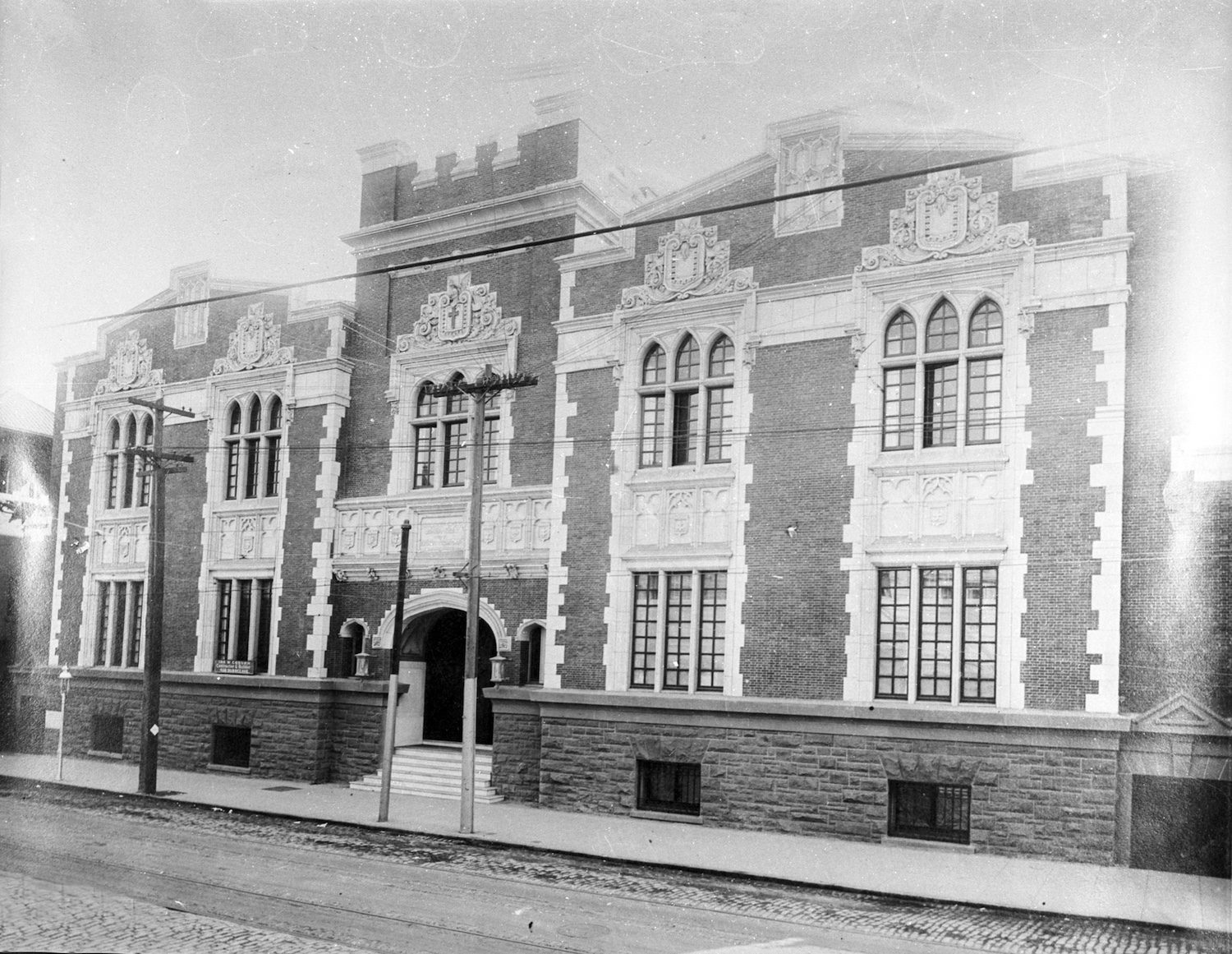

After decamping from Golden Gate Hall, Golden Gate Commandery № 16 met from 1905–1949 in this Matthew O’Brien and Carl Werner-designed temple in the Western Addition, before eventually relocating to San Mateo. The imposing building, built in the so-called “Jacobean phase of the Medieval Revival” style, also hosted several blue lodges, including Occidental № 22, Argonaut № 461, Bethlehem № 453, Educator № 554, and Military Service № 570. That was only the beginning of the building’s history, though: In 1950, it was taken over by Macedonia Baptist Church, an influential Civil Rights-era institution where Martin Luther King twice gave speeches.

The meeting place of King Solomon’s № 260 had only just opened on Fillmore in 1906 when the massive earthquake and fire damaged nearly 80 percent of the city but spared the newly built hall. At that point, the lodge became the de-facto headquarters from which Grand Master Motley Hewes Flint and San Francisco Masonic Relief Board President William Frank Pierce met and organized the disaster response. From there, they and dozens of Masonic volunteers gathered food and goods and raised money for the more-than-50 percent of the city that had been displaced. In all, California Masons distributed more than $300,000 (more than $10 million today), and handed out 74,200 food rations over 43 days.

The number of Scandinavian people doubled in San Francisco between 1900 and 1910, with much of that community centered around the area near Market Street and Dolores. Smack dab in the middle of it was the Swedish-American Hall, built in 1908 and home to several social and fraternal groups including, from 1908 until 1987, Balder № 393, named for the Norse god of light. Initially the lodge aimed to work in Swedish (as similar French, Italian, and German-speaking lodges did at the time in San Francisco), but ultimately settled on English, keeping alive a particular Masonic heritage for nearly 80 years.

On Sept. 25, 1957, Masonic dignitaries and city officials gathered in Portsmouth Square (in what’s now the heart of Chinatown) to dedicate a plaque recognizing the location of the city’s first public school, a one-room schoolhouse opened in 1848 on what was then called the Plaza de Yerba Buena. The school was built on land donated by the Afro-Cuban businessman William Leidesdorff, one of the first leaders of early San Francisco and the first president of the school board. The school itself didn’t last long—it was demolished by 1850—but its legacy as the cultural center of Old San Francisco was long-lasting. “Here churches held their first meetings, and here the first public amusements were given,” read Grand Master Harold Anderson in 1957, quoting the writer Frank Soule. “Not a vestige of the old relic now remains and its site is only recognized by a thousand cherished associations that hover like spirits around its unmarked grave.” In recent years, the plaque has come under scrutiny for its seeming disconnect with the Chinatown neighborhood around it—especially since, for many years, Chinese children were barred from San Francisco schools.

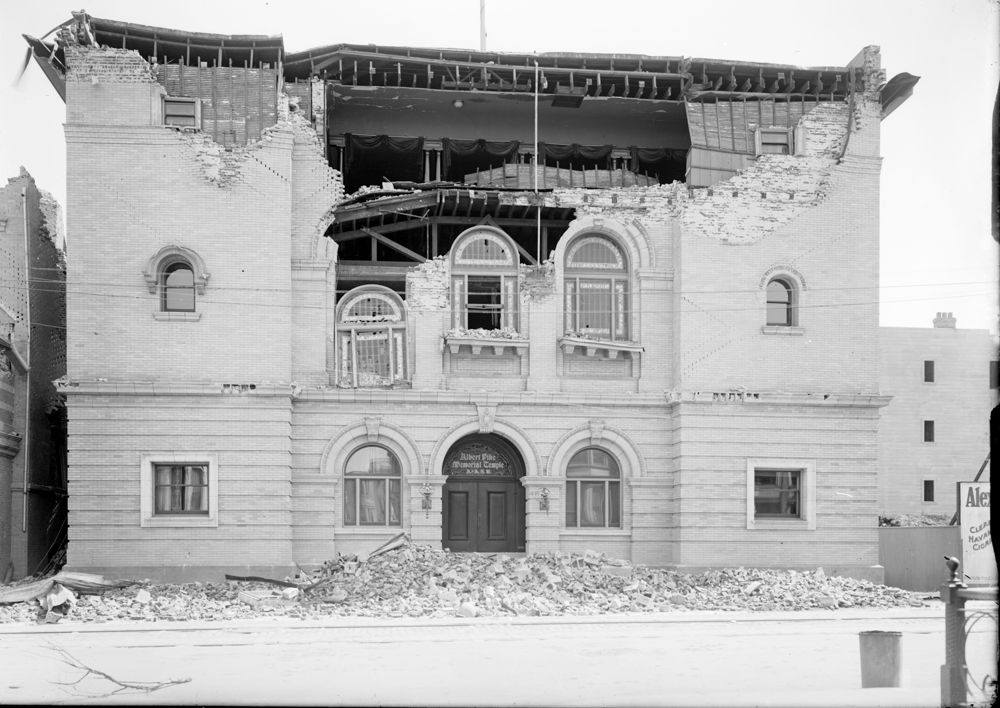

Originally built in 1905 by the Scottish Rite, the temple at Geary near Fillmore had scarcely been opened in time for the 1906 quake. The building, along with its neighbor, the venerable Temple Beth Israel synagogue, were both badly damaged, but were rebuilt and thrived for many years. In the 1960s, when the new Scottish Rite temple on 19th Avenue was opened, the Pike Memorial was left vacant, and in 1971 it was taken over by the infamous Rev. Jim Jones for his People’s Temple—just seven years prior to the Jonestown Massacre. Today, the building is long gone, and the site is occupied by a branch of the post office.

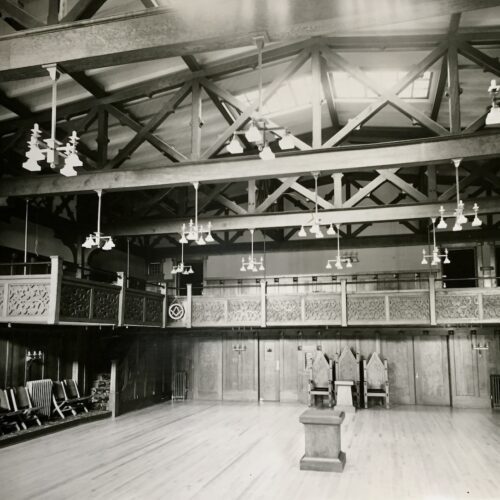

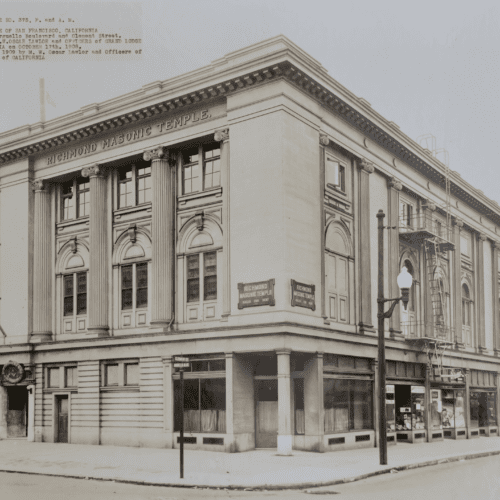

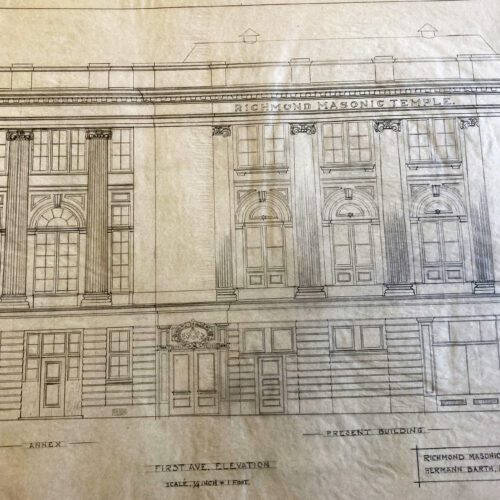

Many of the fraternal flourishes remain inside the 1908 Richmond Masonic Temple on Arguello Boulevard (originally called First Avenue), designed by Hermann Barth, architect of the city’s German Hospital. Engraved Masonic symbols, Corinthian column paneling, and the vaulted ceiling still give a sense of grandeur to what is now a fitness gym. However, the most striking details of the massive building, which was the first major construction project in the Richmond District after the 1906 earthquake, is not part of the original design at all: In 1936, Bernard J. Joseph (who also designed the old Orpheum Theater, on O’Farrell) renovated the building’s exterior in a Mayan Deco theme, with engraved paneling along the parapet at the building’s roofline. The temple was once home to Richmond № 375 and later Lebanon № 495 and Seal Rock № 536.

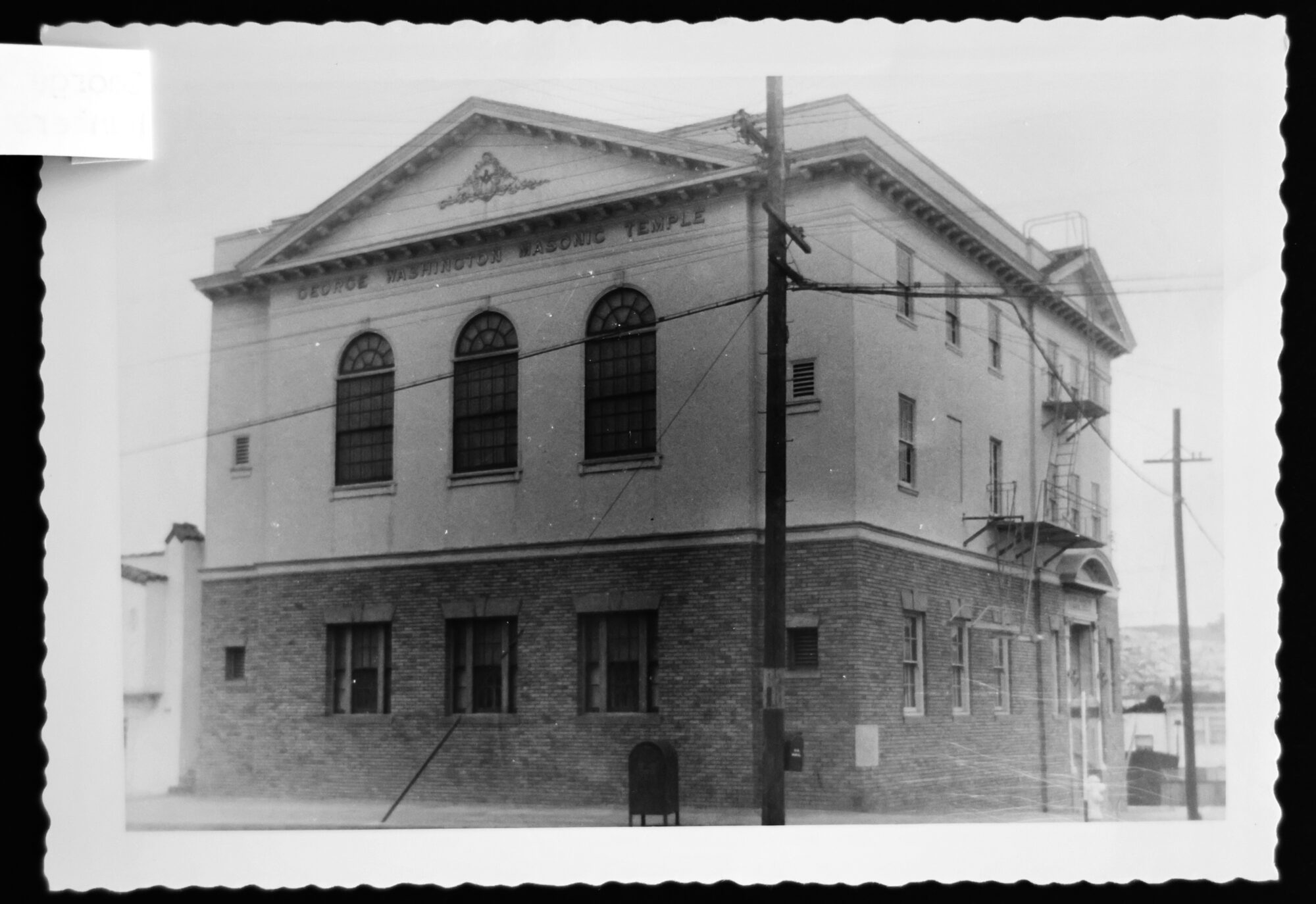

The cornerstone for the future home of George Washington № 525 was laid on Feb. 22, 1923, the birthday of the nation’s first president and just a few months before the dedication of the George Washington Masonic National Monument in Virginia. The San Francisco lodge was somewhat more modest; a three-story edifice in Mission Terrace, near the current City College of San Francisco. In 1974, the lodge began a series of consolations, eventually folding into Brotherhood № 370. The old temple is now a Korean Evangelical church.

Still used by Golden Gate Speranza № 30 and Phoenix № 144, the temple, variously known as the Golden Gate Masonic Temple and Taraval Temple, was first built in 1928, possibly as a Knights of Columbus hall. By 1929, however, it was being used by the Parkside Masonic Association, a group of Masons living in the Sunset/Parkside neighborhood. That group eventually formed Far West № 673 and by the 1940s was sharing space with Mt. Moriah № 44, Paul Revere № 462, and Seaport № 550—lodges that, over the years, have variously consolidated into the two extant bodies.

Right in the heart of the Haight-Ashbury district that birthed the hippie movement, the Park Masonic Hall was opened in 1915 to serve Park № 449. Over the years, it also hosted Victory № 474, Bethlehem № 453, and others. But by the early ’60s, the Masons had left the building, which was later taken over as the I-Beam, the legendary gay dance club, until the 1990s.

The first meeting spot for Mt. Davidson № 481 opened in 1925 just off Ocean Avenue to serve as a “West of Twin Peaks” community lodge. As the city spread outward, the hall began hosting other lodges, too, including Mt. Vernon № 517, Educator № 554, Ingleside № 630, and, for a time, Solomon Chapter № 95 of the Royal Arch. Today the building remains intact and is occupied by a yoga studio.

Prince Hall Masonry has been a fixture in San Francisco since 1852 with the formation of Hannibal № 1, followed shortly after by Victoria № 3 and Olive Branch № 5. Originally, the three Prince Hall lodges met on the corner of Mason and Broadway, in North Beach, which served as the Grand Lodge headquarters. By 1873, Hannibal had moved to the corner of Jackson and Powell, and after the earthquake, relocated to the Western Addition, which became the center of the city’s Black population, first setting up at 1547 Steiner and finally, in the 1940s, relocating to its current, unassuming spot on Bush Street.

The San Francisco Shriner’s Hospital was built in 1922 as the order’s third-ever medical center. Designed by the firm of Weeks and Day (of the Mark Hopkins Hotel), the Italian Renaissance-style hospital accepted young patients for a range of surgeries and physical therapy. North and south wings were added in 1929, and in the 1960s an extension was built to its west. In 1997, with the opening of the new Shriner’s Hospital in Sacramento, the San Francisco branch was sold. Today, following an extensive retrofit, it’s in use as an assisted living facility.

The current home of the Masons of California, the CMMT plays host to more than 250,000 visitors each year, thanks largely to its 3,300-seat auditorium, which has hosted performances from the likes of Bob Dylan and Ella Fitzgerald. Opened in 1958, the 50,000-square-foot temple, clad in Vermont marble, was designed by Albert F. Roller, of Excelsior № 166, who also built the Scottish Rite Temple on 19th Avenue. A “Modernist marvel,” the CMMT was designed to evince “no stylized tradition or cliché.” The most notable ornamentation is the artist Emile Norman’s massive “endomosaic” window made of crushed glass and other material, pressed between panels of acrylic. In 2019, the CMMT opened Freemasons’ Hall, the first-ever lodge room inside the temple, where today eight different lodges meet.

Opened in 1963, the current home of the Scottish Rite was also designed by Albert Roller. Many of the striking artworks at the building, including the exterior mosaic, double-headed eagle, and interior murals, were executed by Millard Sheets, the influential artist and architect. In addition to its use by the Scottish Rite bodies, the auditorium is one of the city’s best-known venues for weddings, graduations, and other large celebrations.

Still standing today, the Gran Oriente Filipino Masonic Temple traces its beginnings to 1921, when a group of merchant marines organized the first California chapter of that Masonic organization. The group served as a community anchor for the first great wave of Filipino workers in California. In the 1930s, they purchased a residential hotel on South Park and eventually built a temple, home to Rizal № 12. That group continues to meet there, and though it has just a few remaining members, it stands as a testament to Filipino and Masonic history in the city.

Photo Credits

1. Birthplace of California Masonry: Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library

4. Michael Reese: Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library

5. Grand Lodge Temple: Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library

6. Golden Gate Hall: Courtesy of California Historical Society Collection at Stanford, Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries

7. Bayview Opera House: Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library

8. Masonic Cemetery: Courtesy of Western Neighborhood Project/OpenSFHistory

9. B’Nai B’rith: Courtesy of the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California, Berkeley

11. D. Norcross: Courtesy of Ian A. Stewart

12. Thomas Starr King: Courtesy of Western Neighborhood Project/OpenSFHistory

13. Emperor Norton: Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library, California Faces: Selections from the Bancroft Library Portrait Collection

14. Golden Gate Commandery No. 16: Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library

15. King Solomon’s Temple: Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library

16. Swedish American: Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry; Courtesy of the Swedish American Hall Library and Archives (2).

17. First Public Schools Monument: Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

18. Albert Pike Memorial Temple: Courtesy of the San Francisco Public Library History Room

19. Richmond Masonic Temple: Via Flickr user eric; via Ian A. Stewart, courtesy of UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives; courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

20. George Washington Masonic Temple: Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

21. Taraval Temple: Via Flickr user Anomalous_A.

22. Park Masonic Temple: OpenSFHistory / wnp28.073

23. Mt. Davidson Temple: Screenshot via GoogleMaps

24. Hannibal No. 1 Prince Hall: Courtesy of OpenSFHistory/WNP

25. Shriner’s Hospital: Photo courtesy of Shriners Children’s Northern California

26. California Masonic Memorial Temple: Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

27. Scottish Rite Masonic Center: Courtesy of Flickr user Heather David

28. Gran Oriente: Photo by Winni Wintermeyer

Four San Francisco Masonic landmarks of yesteryear get a new lease on life.

The influential artists Arthur and Lucia Mathews once designed the interior of the Grand Lodge Temple. So where’s all their artwork gone?

At the French-speaking La Parfaite Union No. 17 Masonic lodge, in San Francisco, a Francophone legacy lives on.