At Downey United, a Mason Leaves an Artistic Legacy

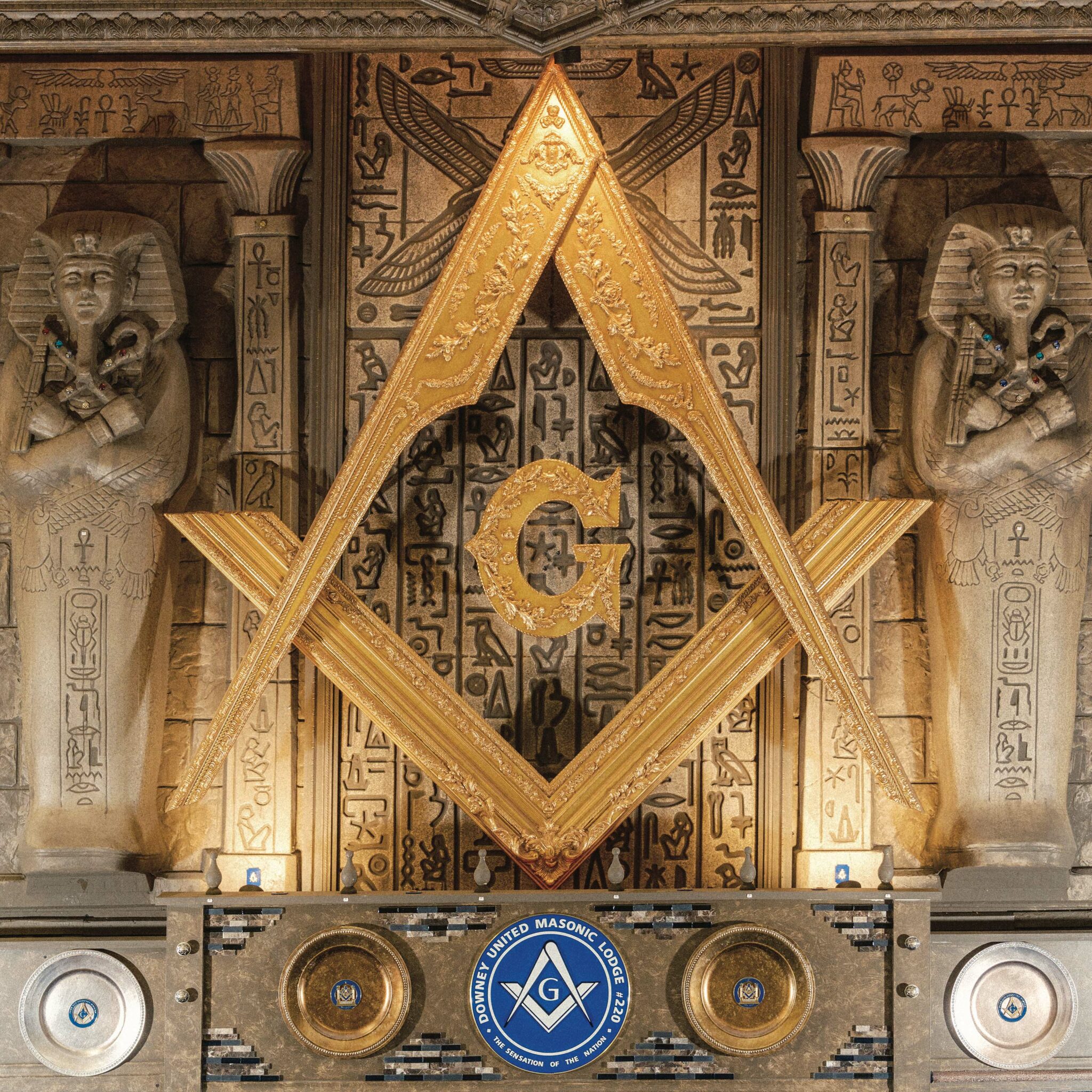

There’s no missing the massive, Egyptian-inspired wall art known as the Raj Mahal, executed by Mason artist Raj Champieri, at Downey United No. 220.

When architect Kevin Hackett was approached about creating the new Freemasons’ Hall, to be housed inside the California Masonic Memorial Temple in San Francisco, his design inspiration came from another age and place. In Britain and Europe, lodges for centuries met in small, cramped spaces either inside, above, or sometimes beneath neighborhood bars and taverns—a practice that lasted until the middle of the 20th century, in many cases.

It therefore seemed appropriate that the only space available for the new lodge room in San Francisco was a corner of the windowless exhibition hall directly beneath the Masonic auditorium, a thundering Live Nation music venue. “Once you choose an esoteric route in life, you end up in some really interesting spaces,” jokes Hackett, the co-founder and principal of the San Francisco design firm Síol Studios and a member of Logos № 861 and Mission № 169.

Five years later, the new Freemasons’ Hall is the meeting place of no fewer than eight Masonic lodges, including Hackett’s Logos № 861. And far from being some dank bar basement, the lodge room is a triumphant blend of rich midcentury aesthetics (clean lines, brass detailing, organic materials) and timeless classicism (marble columns, stepped wooden moldings). But even amid such elevated trappings, the spirit of those bygone gatherings in humble watering holes prevails. To Hackett and others, the result points to the next step for lodges in California: small, special, and endlessly meaningful. “When bigger lodges splinter into more intimate groups, that will be the evolution of Freemasonry,” Hackett says. Here, the architect gives a tour of California’s first “urban microlodge.”

Inherently cozy owing to its interior location in the building, Freemasons’ Hall has a maximum capacity of just 50 people. Accessing the lodge hall requires passing through an adjacent lounge, library, and gathering space, well-appointed with marble columns, channel-tufted velvet sofas, and framed portraits of past grand masters. The handsome library is stacked with Masonic texts, and a central hearth is marked by a mounted sculpture of the Masonic handshake.

Above:

The library and lounge area of Freemasons’ Hall, outside the lodge room, invite members to stay a while.

Hackett’s entrée into Masonry came through the fraternity’s historic connection to builders like himself. “They talk about [building] symbolically all the time,” he says. His lodge design pays homage to that tradition. A pentagon-shaped altar, cut from Italian Carrara marble, represents the spiral creation from the golden ratio. Custom brass screens contain concentric shapes—a circle, triangle, and square— exemplifying oneness among the soul, spirit, and body. French oak stepped molding, also installed throughout the lodge, references the philosophy “as above, so below,” and suggests the duality in engineering between tension and polarity—key in the construction of the pyramids. Even the temple’s barrel-vaulted ceiling is a nod to ancient crypts like the Parisian catacombs and Rome’s Mithraic temple ruins.

The theatrically illuminated sculpture on the temple’s east wall may bring to mind a glowing white moon but in fact reflects the rising sun. Meanwhile, the textural gradient of the marble is a nod to Masons’ lifelong work perfecting the rough ashlar to polished stone. Achieving the effect required a range of tools and techniques from Los Angeles stonemason Nathan Hunt, including a hand-point chisel, bush hammer, and sandblaster.

Above:

The Freemasons’ Hall lounge area and hearth features a mounted sculpture of shaking hands, recovered from the Grand Lodge temple that burned in the 1906 fire.

The lodge room’s location under one of San Francisco’s major concert venues posed a challenge to the quiet and contemplative nature of Masonic rituals. Acoustical engineer Charles Salter masterfully decreased the decibels using a combination of strategies, from 24-inch-thick walls with sound-absorbing air gaps to double-layered acoustic Sheetrock. Even the full-height tufted-leather banquettes built along the perimeter of the temple contribute to soundproofing. The result is that a person speaking in hushed tones can be clearly heard by others around the space, their faint echo lending a reverential air to the proceedings. “In rituals, you’re repeating words that were said centuries ago and never written down,” Hackett explains. “There’s a lot of power in the oral tradition of the Freemasons.”

Above:

The textual gradient of the wall recalls the transition from rough to smooth stone.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY:

Joe Fletcher/Courtesy of Siól Studios

Jose Camello

There’s no missing the massive, Egyptian-inspired wall art known as the Raj Mahal, executed by Mason artist Raj Champieri, at Downey United No. 220.

A skateboarding Mason and installation artist at Yucca Valley No. 802 is shredding perceptions about Freemasonry.

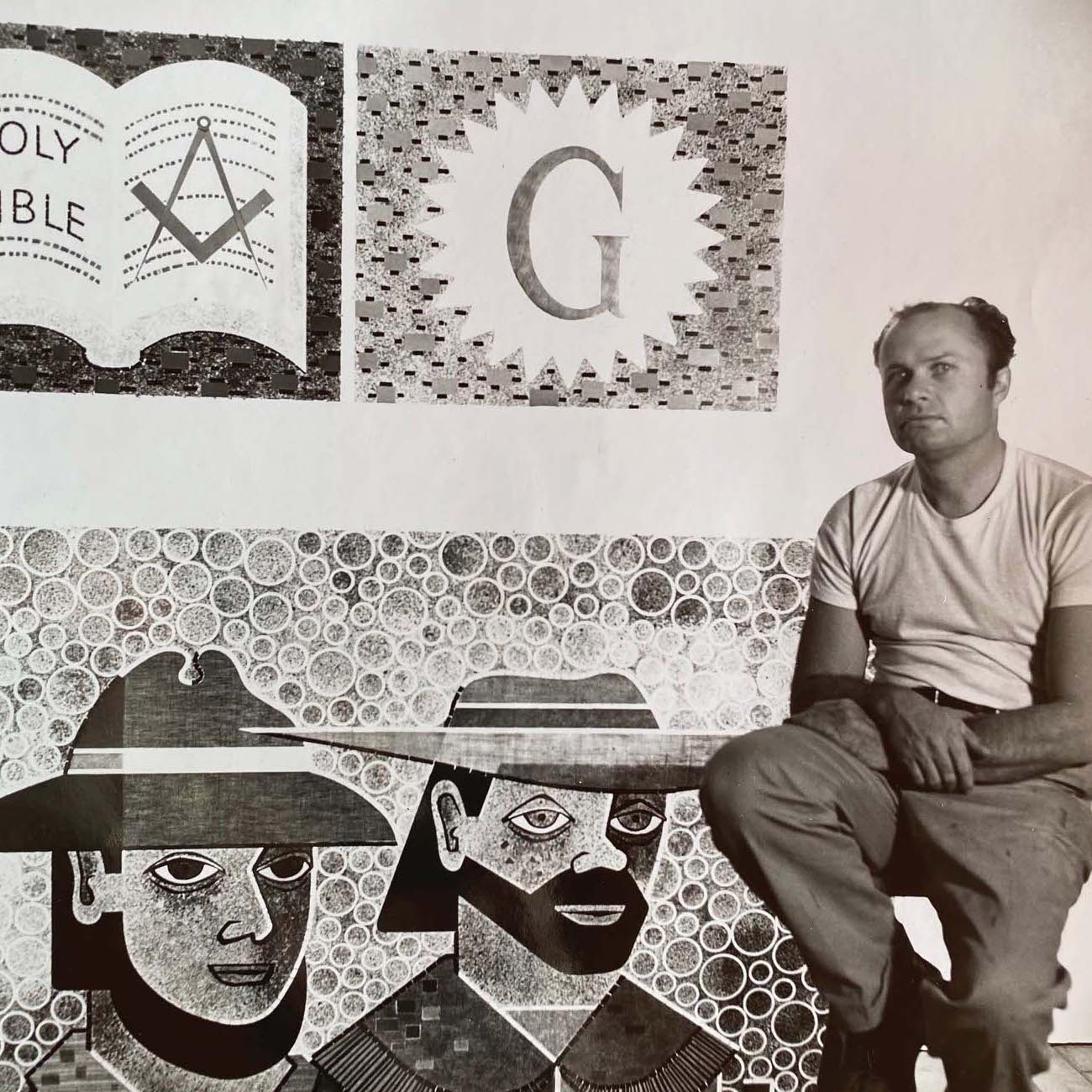

Artist Emile Norman never became a household name. But his massive artwork remains a treasure of California Freemasonry in San Francisco.