Grand Master Wilkins: The Importance of Crossing Borders

Grand Master Jeffery Wilkins on how Freemasonry can help members form bonds with members from other countries, particularly in Latin America.

By Ian A. Stewart

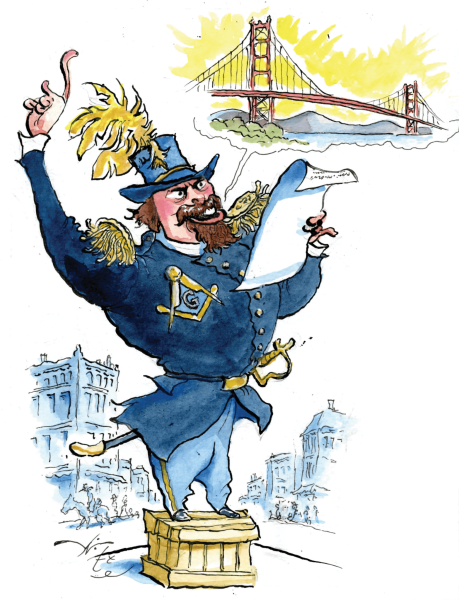

It was an audacious plan, coming from a suitably audacious source. The year was 1872. Joshua Norton, the beloved San Francisco eccentric, Freemason, and self-proclaimed Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico—better known as Emperor Norton—had issued yet another of his frequent “proclamations” to be published in the local press. This time his dispatch outlined his vision for a massive new infrastructure scheme. “We, Norton I, Dei gratia Emperor … order that the bridge be built from Oakland Point to Telegraph Hill, via Goat Island,” he wrote, using the earlier name for Yerba Buena Island.

What Emperor Norton was describing is today called the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. One hundred and fifty years later, John Lumea is on a mission to give credit where it’s due.

Norton’s proclamation, issued more than 60 years before the completion of the bridge, was one of hundreds he’d pen over 20 years. Today, it stands either as an amazing bit of foresight or the ravings of an unhinged dreamer. As is often the case when it comes to Emperor Norton, the truth is entirely in the eye of the beholder.

Lumea knows where he stands on the matter. As head of the Emperor Norton Trust, he’s on a years-long mission to formally recognize the Emperor’s legend by having Norton’s name affixed to the Bay Bridge. Norton, a failed businessman turned oddball-about-town, was a cultural fixture in 1860s and ’70s San Francisco who rubbed shoulders with artists and writers including Mark Twain and Frank Soulé, who along with Norton was a member of Occidental № 22. Today, he’s celebrated as a sort of patron saint of the fraternal order E Clampus Vitus.

“Even though Norton was known as this bombastic character, his concerns were always about the people of San Francisco and figuring out how to help,” Lumea says. “He was able to navigate that in a way that really endeared him to people.”

This year, the sesquicentennial of Norton’s three bridge proclamations, Lumea feels that the time has finally come to recognize him by adding his name to the bridge.

It wouldn’t be nearly as unusual as it sounds, he says: More than 30 bridges in California have ceremonial names—including the Bay Bridge, whose western span is named for former mayor Willie Brown. For all of Norton’s well-chronicled peculiarities—he was often pictured in a military costume, epaulettes, and a beaver-fur hat—he was ahead of his time on matters of immigration, race, and urban development. (He also proposed a subway tube beneath the bay, 100 years before BART made it a reality.)

For that reason, Lumea says, Norton stands as a sort of 19th-century forerunner to the city’s famous countercultural tribes—the bohemians, beatniks, and hippies. “In all these proclamations, he’s talking about things like equality and tolerance and the common good,” Lumea says. “These things became adopted as values of the Bay Area, and the Emperor is talking about them in the 1860s.”

Whether or not that thinking was influenced by Freemasonry is an open question. Regardless, the fraternity was clearly an important part of his life. Norton joined Occidental № 22 (now California № 1) in 1854, and by 1855 was listed in the Proceedings of the Grand Lodge as a Master Mason (suggesting he either progressed quickly through the degrees or affiliated after receiving them elsewhere). He remained connected to the lodge until being suspended in 1859, likely for nonpayment of dues. That’s not surprising: Despite his immense popularity, following a disastrous business caper that left him bankrupt in 1854, Norton lived in a constant state of near-destitution.

Though he died without rejoining the lodge, it was a fellow Mason, Joseph Eastlund, later the head of Pacific Gas and Electric and a member of California № 1, who donated the funds to have Norton buried at the old San Francisco Masonic Cemetery. A century and a half later, his fellow members’ embrace of Norton at both his heights and depths remains endearing, Lumea says. “It certainly says good things about the Masons.”

Above:

Joshua Norton, the so-called Emperor Norton I of San Francisco, was often pictured in a pseudo-military costume. Photo by Bradley/Rulofsen-Wikimedia.

ILLUSTRATION/PHOTOGRAPH BY

Michael Witte

Emperor Norton Trust Fund

Grand Master Jeffery Wilkins on how Freemasonry can help members form bonds with members from other countries, particularly in Latin America.

A road trip through Cuba reveals a thriving—and colorful—Masonic community full of eye-catching Masonic lodges.

In the revolutionary movements of Latin America, Central America, and South America, Freemasons were front and center.