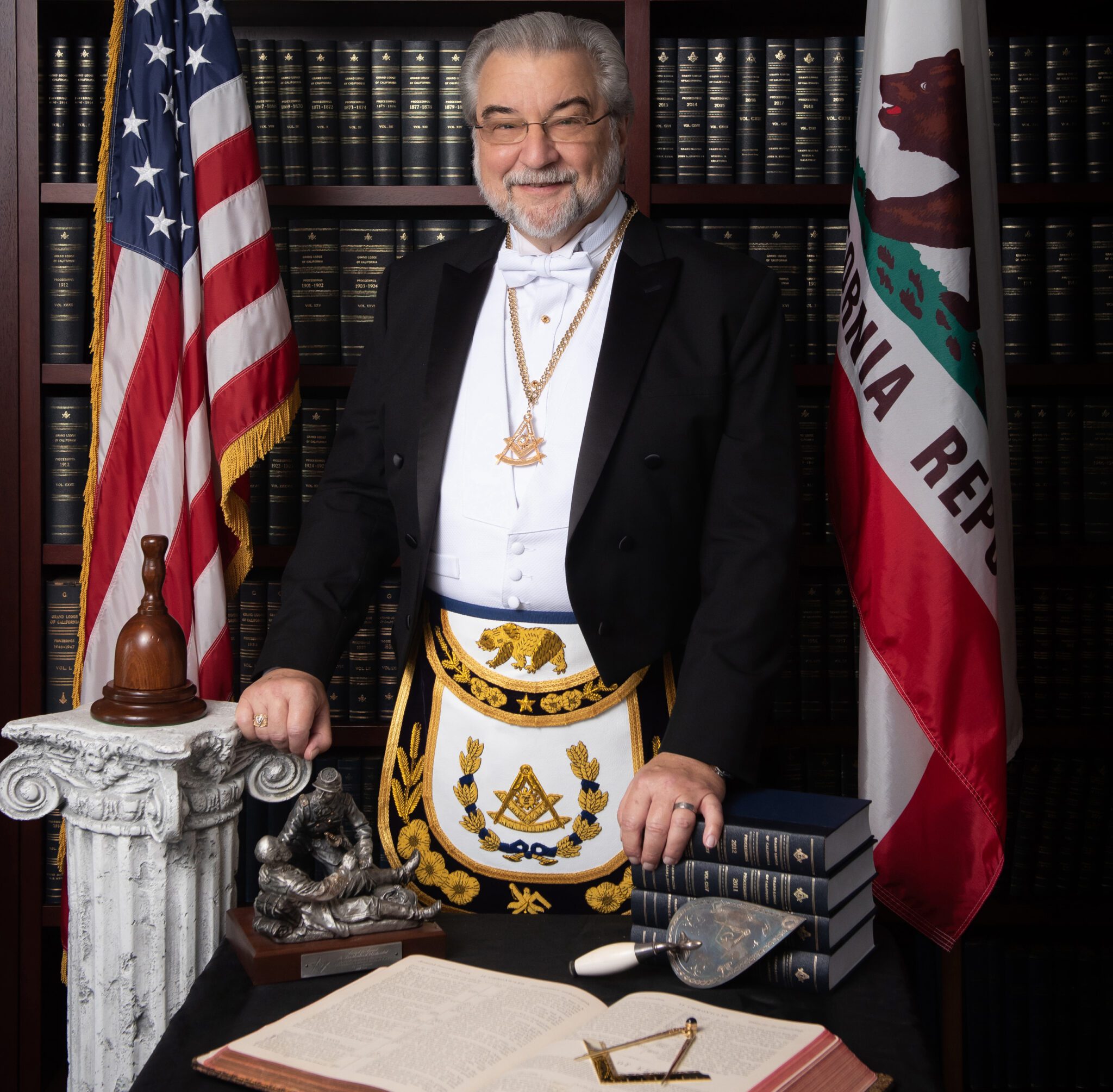

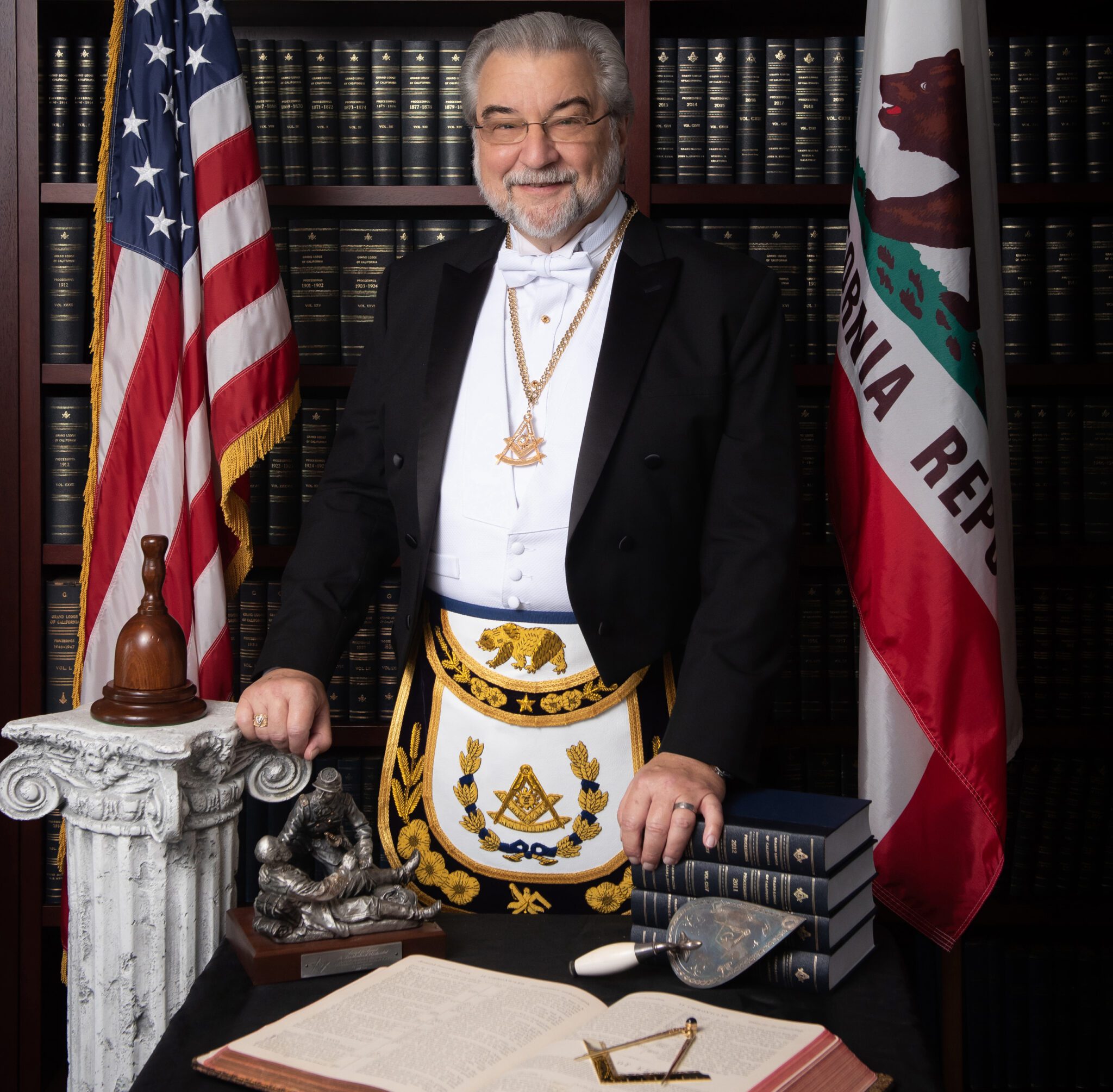

Grand Master Randy Brill: In Small Towns, A Lodge Is a Civic Center

Grand Master Randy Brill explains what small-town Masonry can teach us all.

There are many Masonic temples around the world that, in and of themselves, are works of art, from Zedekiah’s Cave in Israel to St. Peter’s Spiritual Temple—also known as the Voodoo Village—in Memphis. But only one has hosted artworks by the likes of Cindy Sherman, Takashi Murakami, and Glenn Ligon. That honor goes to the former Los Angeles Scottish Rite temple on Wilshire Boulevard—one of the most distinctive and artistically important Masonic landmarks in the country. Built in 1961, the temple has commanded significant attention from the art world since the Scottish Rite moved out in 1994. Most recently, Paul and Maurice Marciano, founders of the Guess jeans empire, transformed the complex into the Marciano Art Foundation, a privately-owned museum housing their 1,500-work contemporary art collection. Following a splashy opening in 2017, the museum abruptly closed in 2019.

The international art dealer Larry Gagosian recently set up shop in the space. Despite that spotlight, there’s one artist associated with the building who has largely been overlooked: Millard Sheets, the real-life Renaissance man who designed it and executed much of its artwork.

Though relatively few people know Sheets’s name today, many know his work. A prolific painter, muralist, and mosaicist of the early 1930s, Sheets was also an important—though never licensed—architectural designer. He is credited with more than 100 buildings, including 42 Home Savings Banks in California, many of which can still be seen. Bank founder Howard Ahmanson offered him the commission in 1953 with this challenge: “I want buildings that will be exciting 75 years from now.” For the Hollywood branch at Sunset and Vine, Sheets combined a 500-name mosaic Roll of Stars, an elaborate stained-glass window depicting the Marx Brothers and Keystone Kops, and a mural honoring the site as the filming location of the of the 1914 film The Squaw Man, the first Hollywood movie.

Possibly Sheets’s most famous mosaic is the University of Notre Dame’s Touchdown Jesus, a 324-panel piece on the school library’s facade depicting Jesus with upraised arms above a collection of Christian saints, thinkers, and writers, all visible from the football stadium.

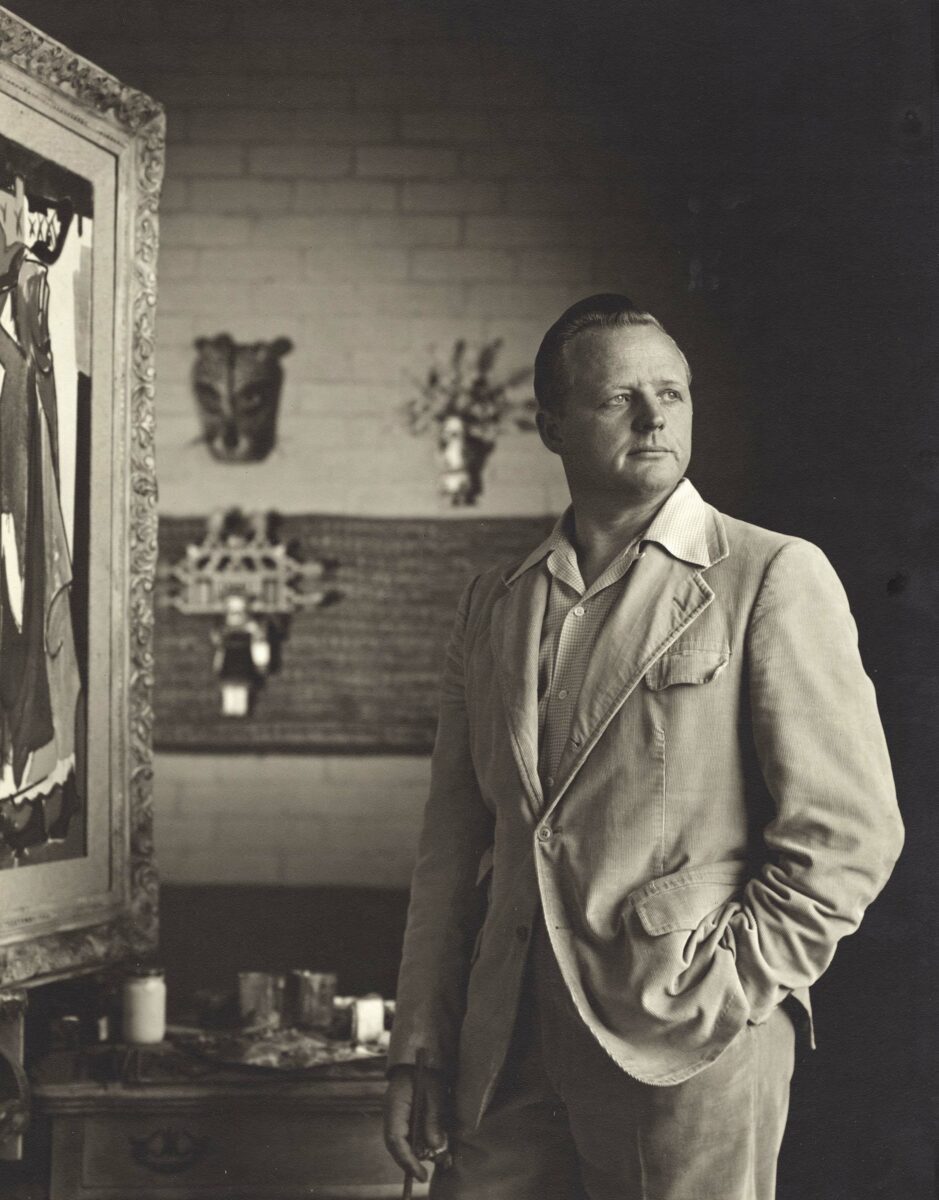

Millard Sheets, artist, architectural designer, and professor, in 1947. Photo courtesy of Claremont Colleges Photo Archive.

That artistic versatility seems to have been an innate gift. Born in Pomona in 1907, Sheets was something of a prodigy. He began teaching art at the Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts) even before he graduated. Prizes and scholarships enabled him to travel to Europe, South America, and Central America. In the 1930s, his oil paintings and watercolors helped define the California Regionalist style, combining a slightly abstract approach with a muted palette in subtle, evocative landscape scenes. Sheets completed a controversial, WPA-sponsored mural series called The Negro’s Contribution in the Social and Cultural Development of America for the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C., and worked with David Siquieros, one of Mexico’s greatest contemporary muralists, on a now-covered mural at Chouinard. He even illustrated a 1939 Fortune article on migrant workers written by John Steinbeck.

As an architectural designer, Sheets did three projects for the Masons, beginning with the L.A. Scottish Rite temple, which he called “one of the most exciting projects I ever had anything to do with.” Though Sheets wasn’t a Mason himself, Ellsworth Meyer, then the head of the L.A. Scottish Rite and a Superior Court justice, nevertheless approached him directly about working on the design for a massive new temple for the order. A special committee of Scottish Rite Masons also approached nine other architectural firms about the commission, all of which included fellow Masons as principals, but ended up selecting Sheets to design the $4.5 million project.

The 110,000-square-foot marble and travertine building remains an endless source of fascination for passersby. On the exterior, eight 14-foot-high sculptures of important Masons, real and mythic, loom over the site, and a 70-foot-tall mosaic tells the story of temple building throughout time. Inside, the marble-clad interior once held a mosaic history of Masonry in California, and it still boasts terrazzo floors, a stained-glass window featuring the double-headed eagle, as well as two decorative, non-Masonic murals. According to art historian Susan Aberth, “It’s one of the most beautiful Scottish Rite temples that ever existed.”

As a non-Mason, Sheets had much to learn about Masonic symbolism. As he did, he grew increasingly intrigued by the project. “I do feel that [Masonry is] a tremendous attempt toward the freedom of man,” he said in a 1970 oral history. “They wanted to depict this in every form.”

That can be seen most stunningly in the four-story-tall mosaic on the east of the building. The image depicts a series of temple-builders, beginning with King Solomon. Moving up the image, one encounters crusaders at Acre, in Jerusalem; a worker at the gothic Rheims Cathedral; the Italian general Guiseppe Garibaldi; and King Edward VII outside Buckingham Palace. At the top is the first grand master of California, Jonathan Drake Stevenson, being installed in Sacramento.

Sheets was energized by the size of the commission— four floors and a basement, including a huge auditorium, 1,500-seat dining room, and a library—and felt that his designs needed to reflect the scale of the organization. The temple opened its doors to 12,000 members in 1961, including Los Angeles № 42, and ever since, has stood as a testament to both the imagination of Sheets and to the generations of Masons who’d built the fraternity. They are gone, but traces of their grand ambitions remain.

Above:

The Scottish Rite Temple on Wilshire Boulevard in L.A., designed by Millard Sheets and completed in 1961. Photo by Mathew Scott.

Grand Master Randy Brill explains what small-town Masonry can teach us all.

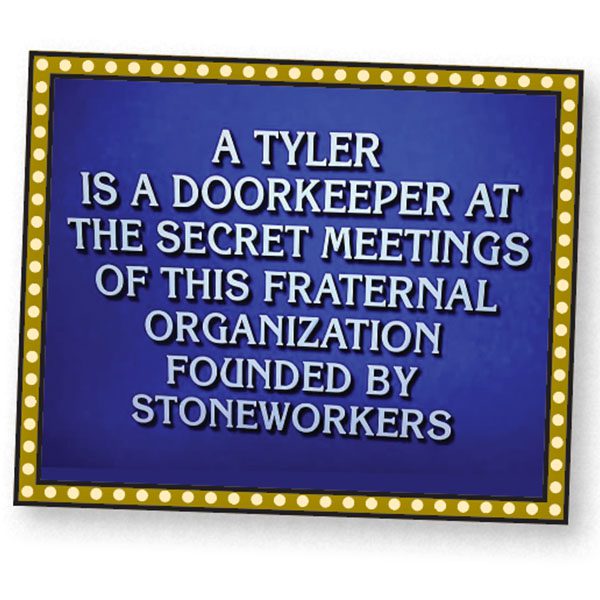

When it comes to the venerable quiz show Jeopardy!, Freemasonry and other Masonic themes are well-trod territory.

Fraternal societies like the Freemasons were born out of ancient, operative trade guilds. They weren’t the only ones.