Eye of the Beholder

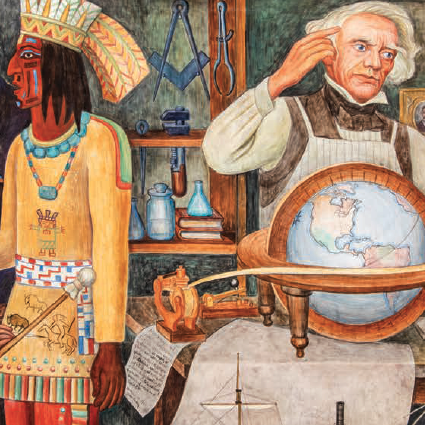

Could a hiding-in-plain-sight Masonic icon change the way we understand a Diego Rivera masterpiece?

By Ian A. Stewart

For Del Lauderback, it was a matter of principle. The longtime preacher and special-needs educator first affiliated with Paul Revere Lodge No. 462 in 1973 (now Phoenix No. 144), and by 1990 he’d joined its officers’ line as junior warden. But a question seemed to grate at him: Given Freemasonry’s commitment to moral uprightness, why weren’t California Masons and Prince Hall Masons, the historically Black Masonic fraternity, permitted to sit together in lodge?

Even 30 years ago, that rule seemed like a relic of an even more distant past—something more likely to be seen half a century earlier in the Deep South than in the Bay Area of the early nineties. So he resolved to do something about it.

As it turned out, there was a simple—if not particularly straightforward—answer. The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, which traces its origins to 1784, has operated continuously in California since 1855 but it and the Grand Lodge of California had never officially recognized one another. As a result, members of the two groups were precluded from pursuing any sort of Masonic work together.

Masonic recognition has long been an important tool for establishing connections between Masons around the world. In recent years, it’s one the Masons of California have used to cement those relationships: Since 1923, when it began tracking it, the Grand Lodge of California has entered into mutual recognition with more than 200 Masonic jurisdictions in the U.S. and abroad, with more than a quarter of those occurring since 2000.

Those links represent an important bond for Masons. Ask any member who’s had the opportunity to attend a ceremony at another lodge and they’ll tell you that the experience is profound—a reminder that the fraternity makes brothers out of people living worlds apart.

So in 1990, Lauderback took it upon himself to introduce a resolution at Annual Communication recognizing the “regularity” of Prince Hall Masonry in California. “A fraternity divided along the lines of color is an anachronism of segregation,” he wrote. The resolution was a trial balloon. Even assuming that a century and a half of nonrecognition could be undone, both grand lodges would need to agree to it for any such move to happen.

So Lauderback agreed to withdraw his motion, with then-Grand Master Ron Sherod pledging to appoint a special committee to work alongside Prince Hall Masons to explore “the possibility and method of an equitable and just union of those lodges with this Grand Lodge.”

There may have been miles of track ahead of them, but to Lauderback and many others, the train had finally left the station.

The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge and the Grand Lodge of California joined one another in mutual recognition in 1996.

Worldwide, there are somewhere in the neighborhood of 500 Masonic grand lodges, each with slightly different traditions, rules, and eligibility criteria. Members of each order consider themselves Freemasons. All of them, however, are barred from visiting or even associating with lodges in jurisdictions that are not recognized by their own. As is often the case with a 300-year-old fraternity, the devil is in the details.

On May 18, 1991, there were lots of details to work through.

It was on that date, in a room at the Oakland Airport Hilton, that the first formal meeting between the Grand Lodge of California and the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California took place. With that, what would become a years-long process was launched to establish the framework for a historic pact. One of the first issues the groups faced was also the most significant: historical precedent. Since before the founding of the Grand Lodge of California in 1850, Masonic grand lodges throughout the country had subscribed to a concept called the American doctrine. Put simply, this established that only one grand lodge could claim jurisdiction over a given territory, and that any other grand lodge working there would be considered persona non grata (or, in the parlance of the time, “clandestine”). Even if a grand lodge wanted to recognize another group within its borders, the American doctrine didn’t allow it. “It was considered a bedrock principle,” explains Past Grand Master John L. Cooper II.

The aim was to impose order on what had become, in certain places during the 19th century, a Masonic free-for-all. The various lodges in a single town might be connected to any number of foreign countries, each of which had its own rules and traditions—and all competing for the same members. To those early Masonic leaders, the very structure and reputation of Freemasonry seemed to be at stake. The American doctrine established a jurisdictional claim in each state. But it also had the effect of marginalizing a great number of Masons—including, in the case of Prince Hall Masonry, many people of color.

Freemasonry has always stipulated that membership cannot be closed to any qualified prospect on the basis of race or creed. Yet, over the past 200 years, the fraternity has reproduced many of the same patterns of discrimination and segregation seen elsewhere in society. Reports from the early and mid-20th century in the Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of California frequently distinguish between “white Masonry” and “colored” or “Negro” lodges. A report on Prince Hall Masonry published in the 1946 Proceedings, summarizing correspondence from North Carolina, read, “The several Grand Lodges of the United States almost without exception limit their membership to the white race.”

The result in many states, including California, was a sort of parallel system, in which the mainstream grand lodge could not and would not formally recognize its Prince Hall counterpart. But neither did it make overt attempts to shut it down. In 1930, the Proceedings referred to Prince Hall Masonry as “quasi-legitimate,” and having “a sort of qualified standing with our Grand Lodge.” By 1938, it stated that Prince Hall Masonry should be “generally termed ‘irregular’ rather than ‘clandestine’ ”—perhaps a semantic difference but also an olive branch.

In 1931, regarding Prince Hall lodges in California, a Grand Lodge report stated that, in fact, “They have been unofficially aided in various ways by officers of the Grand Lodge of California, though no recognition has been or can be extended to them either as a Masonic body or individually.” In 1936, as a show of “cordial feelings” between the two grand lodges, Prince Hall Grand Master Theodore Moss gifted a copy of his organization’s proceedings dating back to 1904 to the Masonic Library of Southern California. “Relations between this Grand Lodge and the white Masons of the state [are] as close as same could be without recognition, and apparently that relationship is satisfactory to both sides,” he said.

Over the many decades, this arrangement remained the status quo. Even to those for whom a parallel system smacked of “separate but equal,” the so-called American doctrine seemed to prevent progress. “That was the big roadblock,” says Frank Russell, who became chairman of the Grand Lodge committee on Prince Hall recognition.

So Russell pored over century-old proceedings books and Masonic writings, looking for the basis for the rule. He wrote to researchers at the Grand Lodge of Wisconsin’s vast Masonic library and found the first references to the doctrine, from around 1840. But what he didn’t find was equally important: The doctrine was not written into a single, binding document. It certainly wasn’t law (though its principle had been enshrined in the California Masonic Code). As far as he could tell, the doctrine was more concerned with protecting a grand lodge’s jurisdictional claim than dictating who it could recognize.

That seemed to leave the committee some wiggle room. “We had a really good lawyer in Past Grand Master R. Stephen Doan,” Russell explains. “Steve said, ‘If we have the right to dictate the confines of our jurisdiction, then we also have the right to recognize who we want to recognize within that jurisdiction.’ And that’s what really opened the door.”

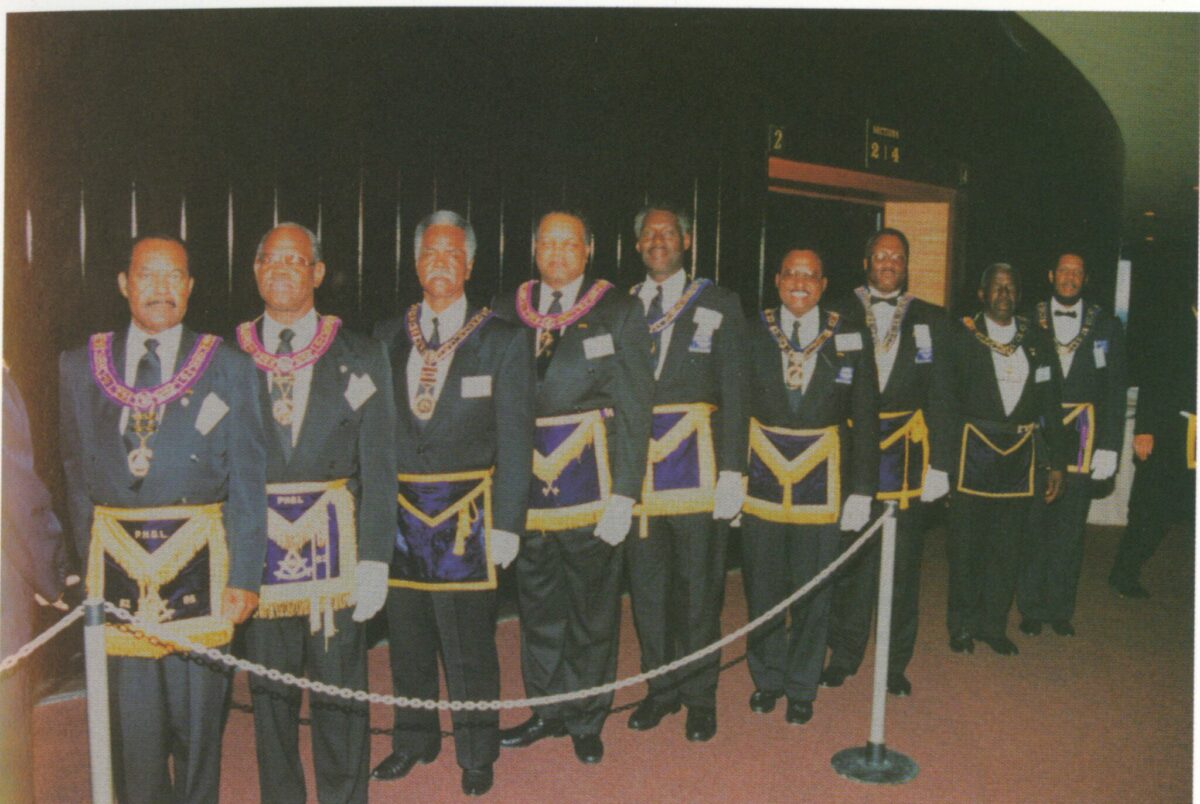

Above:

A meeting of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California in 1955. Photo courtesy of the Oakland African American Museum and Library photograph collection.

Established in 1850, it is by far the largest Masonic grand lodge in the state—and one of the largest in the country. freemason.org

The traditionally Black fraternity accepts members of all races. Established in California in 1855, today it has lodges across the state. mwphglcal.org

Since the revolution of 1979, Freemasonry has been banned in Iran. Today, the Grand Lodge of Iran in Exile is headquartered in Los Angeles and has lodges in several U.S. states and France. (818) 426-6434

With three lodges in Los Angeles, this body is connected to the United Women’s Grand Lodge Alma Mexicana. wglca.org

The largest of several French orients includes two California lodges: Art et Lumière in Los Angeles and Pacifica Lodge in San Francisco. Both admit men and women. godf-amerique.org

Connected to the International Order of Mixed Freemasonry, LDH practices mixed-gender Masonry, with several lodges in California. Members do not need to express a belief in a deity. freemasonryformenandwomen.org

Founded in 1999, Lodge Aletheia No. 32 in Los Angeles is one of the f ew women’s lodges in the U.S. connected to Belgium. wfmla.com

Left:

Grand Masters Russ Charvonia and Donald Ware laid a ceremonial cornerstone for Willie Brown Elementary School in San Francisco in 2015.

Meanwhile, other details of the agreement were being ironed out by the two committees, including some tricky business related to Prince Hall’s presence in Hawaii, which has its own grand lodge. The biggest remaining holdup was a Prince Hall rule pertaining to plural lodge membership. Whereas California Masons are able to hold membership in several lodges, Prince Hall limits membership to a single lodge. Prince Hall leaders were adamant that the rule remain in place, in part as a way of guarding against membership drain. “There’s a strong heritage behind both grand lodges,” says Prince Hall Past Grand Master Samuel King. “Neither one wanted to lose its identity.”

Respecting that tradition became a priority during negotiations. And as the sides made progress toward an agreement, the two grand lodges began to work alongside each other for the first time.

In 1993, then-Grand Master R. Stephen Doan became the first California grand lodge officer to address a Prince Hall grand session when he delivered a speech during its annual Sunday religious service. The same year, Prince Hall Grand Master Harold Mure returned the favor. The following year, representatives from both parties followed suit. In July of 1995, Deputy Grand Master Charles Alexander became the third California officer to speak at a Prince Hall service, this time directly addressing the matter of recognition. “I find it gratifying that the walls which once totally separated us are, like the Berlin Wall, beginning to crumble,” he said. “Some of our more skeptical brethren have asked me, ‘What do we expect to gain by seeking mutual recognition with Prince Hall Masonry?’ My answer to that is ‘Gain? We are not seeking gain, but seeking that which is just.’ ” He received a standing ovation.

Finally, in 1995, five years after Lauderback’s trial resolution set the ball rolling, and with most of the major agreements in place, the committees drafted virtually identical motions establishing mutual recognition between the Grand Lodge of California and the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California. “Masonry was designed to be a brotherhood of man, which need not be an idle dream in the great state of California,” said then-Prince Hall Deputy Grand Master Ronald Robinson.

The Prince Hall body passed the resolution unanimously. At the Grand Lodge of California’s Annual Communication, it passed 1,392 to 124—nearly 92 percent in favor. “History is continually being made up and down this shared jurisdiction,” declared a special issue of the Prince Hall Masonic Digest. “The barriers are down. There are no more excuses. All have the good work to do; the bridge has been built.”

Above:

Members of the Grand Lodge of California and the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California joined in laying the cornerstone for the new basketball arena in Sacramento.

Far from being merely some procedural vote, mutual recognition has opened the door to a new level of cooperation between the two grand lodges. In so doing, it helped deepen the fraternal experience for Masons of all stripes. Since 1996, when the agreement took effect, the Grand Lodge of California has entered into mutual recognition with 35 other Prince Hall grand lodges across the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, and elsewhere. In turn, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California has similarly entered into recognition agreements with the United Grand Lodge of England and countless other bodies.

In February 1996, Grand Master Charles Alexander’s home lodge, Oxnard No. 341, and Prince Hall Grand Master Joseph Nicolas’s Unity No. 22 made history by convening California’s first intralodge meeting. It was only the beginning. Representatives of both grand lodges now regularly attend one another’s Annual Communications, and countless Masons have been allowed to peer behind the curtain and sit in on one another’s workings. “There’s been an opening of arms on both sides,” says King, the Prince Hall past grand master. “It’s been outstanding.”

The partnership has also extended beyond the lodge room. California Grand Lodge and Prince Hall Grand Lodge Masons work together on philanthropic efforts including the Masons4Mitts glove drive and have attended numerous public ceremonies together. That was strongly in evidence in 2014 when more than 400 Prince Hall Masons and their California Masonic counterparts came together to lay the cornerstone for Sacramento’s new basketball arena—sending an important, visible signal that California Freemasonry is bigger than any one grand lodge.

That, say leaders of both groups, is the future of the fraternity. And while recognition is indeed an important tool, it isn’t the only way to work together. Says Aaron Washington, Prince Hall’s senior grand warden, through Masonic partnership, “If you have a good idea for something you want to do in the community, it’s fantastic that you can get some folks together that are like-minded. There’s nothing more beautiful than that.”

Official recognition has its limits, too: Cooper points out that there are some half-dozen other grand lodges operating in the state, only two of which are formally recognized by the Grand Lodge of California. But increasingly, members of the other Masonic groups have been invited to participate in events with the Grand Lodge of California, including the California Masonic Symposium. Most memorably, in 2015, the Grand Lodge of California, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California, and the Grand Lodge of Iran in Exile cohosted the World Conference on Freemasonry, sharing the stage together as equals.

For Russell, recognition wasn’t just historic. It was personal. Though the committee has long since dissolved, Russell is still liaison to the Prince Hall Grand Lodge. Each year, he attends its Annual Communication, and he often sits in on degree nights for the three Prince Hall lodges in Sacramento. In 2001, then-Grand Master of Prince Hall Masons Herbie Price presented Russell with a plaque declaring him an honorary member—making him, in all likelihood, the only dual member in the history of the state.

“From the moment I was asked to be on that committee, I’ve always felt that this was my calling,” Russell says. “It was like nothing I’ve ever done before and nothing I’ll ever do again. It was something I was meant to do.”

PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION AT TOP BY

Brian Stauffer

Could a hiding-in-plain-sight Masonic icon change the way we understand a Diego Rivera masterpiece?

Why a California Mason and financial planner is planning for his own death.

In Barstow, one lodge’s reputation for camaraderie is known for miles around.