Executive Message: In Perfect Harmony

California Masonic Grand Master Arthur Weiss expounds on the timeless values behind the 2025 Fraternity Plan.

By Ian A. Stewart

No matter how many times Will Maynez looks over the massive Diego Rivera mural known as Pan American Unity, he’s always struck by something new. Maynez is the conservator in charge of maintaining the 74-foot-long, five-panel work, which this summer was relocated, in a feat of engineering, from its home at San Francisco City College to the first-floor atrium at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where it will be on display until 2023. Lately, though, when Maynez looks over the piece, he’s been struck by a less obvious motif: Freemasonry.

While Rivera, the revolutionary artist and Communist champion, is not often associated with Masonry, Maynez says there are hints and suggestions of the craft aplenty in Pan American Unity—if you know where to look. As Maynez, who is not a Mason, began studying the work, Freemasonry provided him with several important clues.

The Masonic reference that requires the least unpacking is near the bottom-right of the mural, where an interlocked square and compass can be seen behind Samuel Morse. That’s no accident, Maynez says. Morse is one of eight Masons depicted in the work. In fact, Pan American Unity isn’t Rivera’s only work to include the working tools: His mural at the Secretaría de Educación Pública in Mexico City also features a square and compass.

Above:

Pan American Unity is on display until 2023. Visit sfmoma.org for more information

So what’s behind these nods to the craft?

There’s no evidence that Rivera was ever a Mason, though he was certainly familiar with the fraternity. Rivera’s father, Don Diego de Rivera Acosta, was a 33º Mason in Guanajuato, and Rivera’s grandfather may have also been a member. Even the doctor who delivered Rivera as a baby was a Mason.

More importantly, Masonry would simply have been in the air for Rivera, who came of age during the Mexican Revolution. Freemasonry was considered an important influence among the professional class of the time and would have represented a liberal, egalitarian ideal for a democratic nation. Rivera’s antagonism toward the Catholic church would also have given him a common cause with many Mexican Masons.

Plus, it’s no secret that Rivera was drawn to mysticism and esoterica. Many of his works, including Pan American Unity, draw parallels between mathematical equations and the natural order. Juan Coronel Rivera, the painter’s grandson, told the New York Times, “Diego was looking for knowledge first, the great knowledge of the human being, the notions of space and time.” In 1926, Rivera joined the Quetzalcoatl Lodge of the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, where his mural La Serpiente Emplumada still hangs.

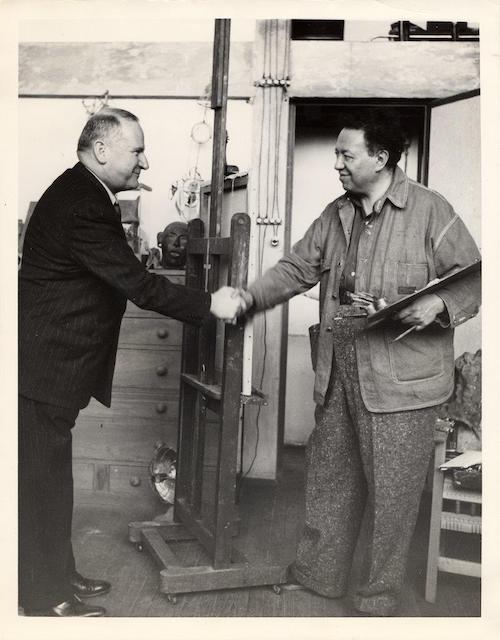

During Rivera’s two visits to San Francisco, the artist was surrounded by Masons. Foremost among them was Timothy Pflueger, the architect behind many of the city’s Beaux Arts and Art Deco treasures, including the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Building on Montgomery Street. Pflueger commissioned Rivera’s fresco Allegory of California at the Pacific Stock Exchange in 1931, and then Pan American Unity for the 1940 Golden Gate International Exposition. Pflueger was made a Mason in 1922 at Amity Lodge No. 370 (now Columbia–Brotherhood No. 370), and was also part of the Scottish Rite and the Shrine. Pflueger, a close friend of Rivera’s, is depicted in Pan American Unity holding blueprints of City College’s main library.

Above:

A square and compass can be seen behind Samuel Morse (second from right) in Diego Rivera’s Pan American Unity.

In a painting that pays homage to the mysticism and indigenous traditions of Latin America and the industrial pioneers of the United States, it makes sense that Masonry would be represented.

How clear that representation was meant to be is, well, unclear. Maynez points out that the square and compass insignia wasn’t included in Rivera’s initial drawings for the mural, meaning that it was a late addition to the piece, perhaps even painted spontaneously. “There are so many Masons in the mural,” Maynez says, among them George Washington, Simón Bolívar, and Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, the leader of the Mexican War of Independence. “As he was painting, I think this idea of Masonic influence became a much more conscious theme.”

But the Masonic allusions run even deeper, he says, at least for those willing to bend their minds in that direction.

The mural is framed by two large, vertical columns—at left a Toltec stela and at right a wooden screw and press. In them, Maynez sees a visual echo of the twin columns of Solomon’s Temple. Between the fourth and fifth panel of the mural is another, unfinished column. To one familiar with the Master Mason degree, there’s a visual echo there of the broken column symbolizing mortality. Taken together, the three columns have a parallel in Masonry, representing wisdom, strength, and beauty.

There’s more: A single human eye, in the massive form of the Aztec deity Coatlicue, calls to mind the all-seeing eye; while the figure of Morse, standing directly beside the square and compass, is pointing to his ear in a gesture similar to one of the signs of the Mark Master Degree of the Royal Arch.

From there, the clues begin to spiral into a sort of feverish speculation: Workers holding Masonic tools including the hammer and chisel. An apron adorning a wooden Indian. A five-pointed star. The helical shape made by Native porters circling a mountain. The rabbit hole goes deeper. “These are big ideas about how the world works,” Maynez says. “What I’m really looking forward to is people seeing it and saying, Well, here’s something new—something that hasn’t been obvious to me at all.”

Pan American Unity is on display until 2023. Visit sfmoma.org for more information.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO BY

Cayce Clifford

California Masonic Grand Master Arthur Weiss expounds on the timeless values behind the 2025 Fraternity Plan.

A historic Masonic temple in Vallejo finds new life as artists’ lofts.