Lodge Profile: Ask Us Anything

A resort-town Masonic lodge goes digital—and the prospects follow.

By Drea Muldavin-Roemer

It’s hard to imagine that 100 years ago, when she first launched the Order of Job’s Daughters, Ethel Wead Mick could have conceived of Sheryl Sandberg’s “lean in” mantra. Or of hashtags like #GirlBoss and #MeToo. Yet for the millions of “Jobies” that have come through the organization over the past century, the concept of young women as self-actualized, empowered, and equipped to thrive in the classroom and the boardroom is anything but new. “We teach girls to have a seat at the table,” says Becki Lane, a high-ranking supervisor of Job’s Daughters California, one of four Masonic Youth Orders operating in the state. “What was novel in 1920 to give these girls is essential in 2020.”

Today, that spark can be seen in young women like 18-year-old Julianna Barnes. A second-generation Jobie, she has been affiliated with the group since she was 10 and is a past honored queen of Bethel No. 97 in Burbank, the highest role within her local chapter. This year, Barnes is serving as Miss California, the organization’s representative at statewide Masonic conventions. It’s a job that combines elements of management, public speaking, and maybe even a dash of political maneuvering. At an age when many teenagers can come off as sullen or disinterested, Barnes radiates competence and charisma—qualities she credits to the organization. “One of the biggest values that Job’s Daughters has had in my life is that it has exposed me to a variety of people of different backgrounds,” Barnes says. “It has truly opened my eyes to the spectrum of the world.”

As Job’s Daughters International celebrates its centennial this summer, the timelessness of its mission continues to resonate, even in a world that would be hardly recognizable to its founder.

The world has changed enormously for women over the past 100 years, yet the need for leadership training and academic support is as important as ever—a testament both to the foresight of Job’s Daughters and also, sadly, to the stubborn persistence of gender gaps in education and the workplace.

Job’s Daughters was launched in 1920 in Omaha, Nebraska, by Ethel T. Wead Mick, affectionately remembered as Mother Mick, at a critical moment in the women’s suffrage movement. (The 19th Amendment was ratified that summer.) The order aimed to provide young women with an opportunity to guide one another in developing into adults of “high moral character, strong intellect, and poise,” according to the group. Wick took her inspiration from the Book of Job, with its story of the equal treatment of women, and particularly the passage, “In all the land were no women found so fair as the Daughters of Job, and their father gave them inheritance among their brethren.”

Mick, who was already active within the Masonic-affiliated Order of the Eastern Star, opened her organization to young women aged 13 to 18 who were related to a Master Mason and proclaimed belief in a supreme being, regardless of their specific religion. (The qualifications for entry have changed over time; today, anyone between 10 and 20 can join if sponsored by a Mason.) Upon its founding, the organization stressed moral and spiritual development through reverence for God, loyalty to the U.S. Constitution and government, and respect for parents and elders. Bethels, or local chapters, were run similarly to Masonic lodges, and often inside lodges: Under the supervision of adult deputies, Jobies elected their leaders, ran meetings according to parliamentary procedure, and planned community service and fundraising events, along with frequent parties, dances, and outings with the group.

During meetings, members wore a distinctive uniform of white Grecian dresses, symbolic of their equality within the group. Officers wore capes and crowns, representing authority and responsibility. Today, the group continues to share Masonry’s reverence for ritual, and members still wear the original garb. However, the group’s aim has shifted from internal development to focus on more external matters, like college readiness and executive skill building. (The Job’s Daughters Foundation issues several academic and vocational scholarships to members at both the state and national level.) “We still hold true to poise and grace,” Barnes says, “but we really pay attention to building members up to be powerful leaders.”

Much like Masonry, Job’s Daughters requires steadfastness and commitment to move up the ranks. It takes two and a half years to go through the five positions in the officer’s line, ending with a term as honored queen. With every subsequent position comes a new level of executive responsibility, including event planning, fundraising, and communications. Honored queens must budget for and plan their own installation ceremonies—an often complicated and complex process. “That progression and serving as honored queen allows them to build the confidence they need,” says Teri Steig, who joined at 13 and is still active as a grand guardian—one of the top adult leadership positions within the group.

The result is that upon completing their term, Jobies are well prepared for college and for careers thereafter. While some of the most celebrated alumnae have been performers—including actresses Judy Garland, Kim Cattrall, and Aimee Teegarden (a past honored queen of Bethel No. 244 in Downey)—leaders today also credit the group’s influence on former Job’s Daughters like Nannette Hegerty, who in 2003 became Milwaukee’s first female police chief. Other exemplars include alumnae like Lonna Seibert, a Harvard graduate and an archaeologist with the Smithsonian Institution, and the young-adult sci-fi novelist and video game designer Jean Rabe.

Despite tremendous advances, when it comes to leadership positions at large, women continue to go woefully underrepresented. While they made up 48 percent of the workforce in 2019, women occupied only 21 percent of C-suite jobs at major U.S. corporations; women also claimed less than a fifth of all board seats at large public companies. Numbers like those speak to the enduring need for leadership training—something that Job’s Daughters is well positioned to offer. “We encourage our members to grow up to be strong young women,” Steig explains, “and to be skilled in business before they even get to the business world.”

Those involved with the organization praise its aims and say it undeniably helps those it serves. However, like so many other service-focused youth organizations today, it’s reaching fewer people than ever before. For context, the Girl Scouts of America has lost nearly 40 percent of its members since 2003; the Boy Scouts, which declared bankruptcy earlier this year, has seen an almost 50 percent decline in enrollment since its high in the 1970s. There is wide speculation about what is behind that drop—including, for some, a belief that such groups are simply too old-fashioned. In their place, a whole swath of skill-building programs have flourished: sports camps, hackathons, STEM retreats.

Rightly or wrongly, the perception of datedness has been a difficult one for Job’s Daughters and others to shake. Today, Job’s Daughters International serves 11,000 youth members across 681 bethels in the United States, Canada, Australia, the Philippines, and Brazil. In California, there are some 800 members in 82 bethels, and 85 Jobie-to-Bees, as the under-10 feeder program is known.

Those involved with Job’s Daughters see encouraging signs at the local level. In bethels that have a strong connection to a Masonic lodge and a deep bench of volunteers, members’ experience is enriching and positive. Adult guardians, majority members, and Jobies themselves create a version of the organization that suits their needs—funding scholarships, volunteering, and organizing events that are meaningful to members. And that, it seems, is a two-way street: The adults involved with those bethels get plenty back in return.

While Job’s Daughters is an organization by and for young women, it also has had a profoundly positive impact on Masons like Jeff Schimsky, past master of Los Cerritos Lodge No. 674 in Long Beach. Schimsky brims with excitement at the mention of Bethel No. 161, to which his daughter, Sloane, belongs and where he’s an associate guardian. “It brings me such joy watching her gel with other girls and be supportive of their successes and their failures,” Schimsky says.

The bethel also brings the best out of Schimsky’s fellow Masons. Several members, including Geoffery Matlack of Bellflower No. 320, and past masters Bill Melanson (Los Cerritos No. 674) and Bill La Valley (Greenleaf Gardens No. 670), have all had daughters rise through the bethel and have volunteered in different capacities. For Masonic dads, Schimsky says, Job’s Daughters represents a unique avenue for connecting with teenage daughters—not always an easy bunch—and for deepening their Masonic bonds. “They all serve big and care really deeply,” Schimsky says of the cohort.

The bethel meets inside the Lakewood Masonic Center, which it rents free of charge from Lakewood Masonic Lodge No. 728. Members of both groups are frequently invited to each other’s events, and even provide support in other ways. A few years ago, when a JDI member’s father died, Masons established a scholarship fund for her.

For Jobies, mixed events are a way to make connections with adults that may someday help them with career advice, internships, and even jobs; for lodge members, they’re a heartening reminder of Masonry’s influence on the next generation. Most of all, Schimsky says, Job’s Daughters enables him and his daughter to share a unique bond. “There’s no other place where you can actually watch a daughter of yours grow into such a leader,” he says.

When Becki Lane, the current grand marshal of Job’s Daughters California, looks back, she’s struck by how well the organization prepared her for life outside the bethel. “I came into Jobies very shy,” Lane, now 49, explains. “But I found my confidence and discovered that I was a good person.”

As a Jobie, Lane learned to facilitate group meetings, develop an agenda, establish and serve on committees, create and present reports, and speak publicly. After college and graduate school, those became important traits when she landed her first job, at Paramount Pictures. “It was all the skills we give our girls from a young age—the poise, the public speaking, the organizational aptitude,” she says.

Despite that emphasis on leadership development, Job’s Daughters International is not simply a school-to-management pipeline. It is also a safe, nonjudgmental space in which girls create friendships and benefit from the support of mentors and peers—things that can be hard to find in the dog-eat-dog world of high school. Barnes, the current Miss California, knows that from experience. “I joined right before I went into middle school. My parents got divorced, and all these things started happening. Job’s Daughters was like a constant,” she says. “A lot of girls need that in their lives.”

For as proud of its traditions as Job’s Daughters is, the organization has made efforts in recent years to appeal to a new generation. Fittingly, the members themselves are responsible for that push. Bethels all over the world now regularly communicate on Instagram, on Facebook, and through YouTube channels.

Comfort with social media has other benefits, too: During the COVID-19 lockdown, Jobies adapted quickly to a world of FaceTime hangouts and ritual practice on Zoom. The group even held a virtual leadership camp focusing on self-care. Older members organized Friday night online parties.

Other changes are in the works, too. Steig is working on a database project to improve membership programs and external media drives. The project will also help members track their accomplishments for résumé building and college or scholarship applications, and provide a portal for online education.

Steig points out that JDI has seen a modest bump in membership recently, another cause for optimism. However, all involved say the key is to retain what’s made Job’s Daughters special these many years. Whether they belonged three decades ago or joined just recently, members say going through Job’s Daughters is a journey of transformation—from girlhood to womanhood, from self-doubt to empowerment. “A hundred years later, that journey is still timeless,” Lane says. “We introduce these girls to the women they are going to become. It’s an amazing privilege to see them find themselves.”

ILLUSTRATION CREDIT:

Chen Design Associates

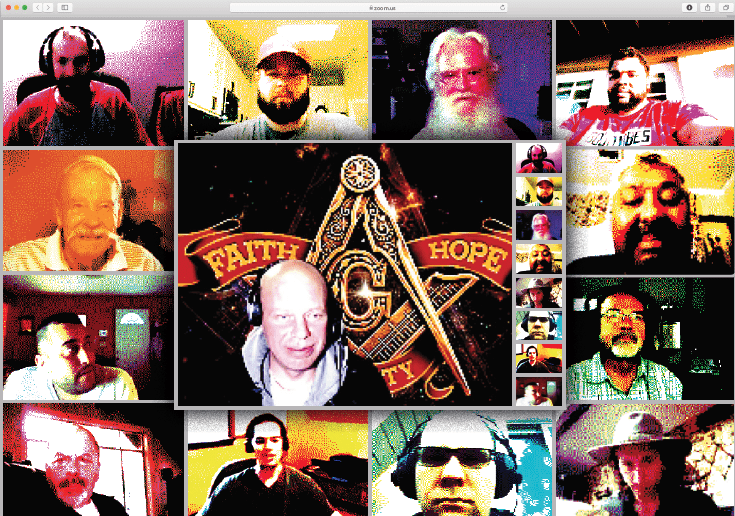

A resort-town Masonic lodge goes digital—and the prospects follow.

Why a first-time donor summoned his father’s memory in giving to the DWB Relief Fund.

Why Masons are in a prime position to affect the world their girls step into.