Ask Me Anything

For a generation of Freemasons, the place to turn for info isn’t in person, but rather online.

By Antone Pierucce

A young man steps off the hyperloop tram, straightening his square-and-compass lapel pin. He’s approaching a downtown museum where he’ll soon enjoy a seven-course meal, followed by a lecture on 18th-century Masonic esotericism. Although the lodge that organized tonight’s event meets only occasionally, he’s glad for the chance to gather with a group of fellow history lovers. His Masonic calendar has been busy lately: Last week he met with his charity lodge; a virtual gathering of Masonic video-gamers is planned for the following week; and his home lodge is preparing for a degree ceremony the week after that.

This imagined future of California Masonry isn’t as far off as it might seem.

The lodge of tomorrow—and thus the Masonic experience of tomorrow—will surely be different from today’s, which in form and size hasn’t changed much in half a century. But that façade of uniformity belies a more fluid past: Since the formation of the Grand Lodge of California more than 170 years ago, Masons have met in everything from ornate temples to tiny lean-tos. Indeed, the lodge as a concept was never intended to be immutable, and the lodge of tomorrow won’t be any different.

California’s Masonic lodges have always reflected the lives of their members. The earliest gatherings were tiny congregations in mining camps where people from around the world established a network of mutual support. By midcentury, the expanding postwar middle class helped lodges grow into enormous civic institutions with several hundred members looking to participate in a shared experience. Now, increasingly, California lodges are adapting to reflect a nimbler generation in search of profound personal experiences.

To get a glimpse of Masonry’s future, look no further than the trio of California lodges currently under dispensation. Each typifies important social and cultural trends, and together they point the way to a likely future for the craft. Each is intentionally small, mobile, and unencumbered by the administration of a lodge hall or temple.

Most important, each of them is organized around a clearly expressed raison d’etre. Whereas in the past lodges were established where demand exceeded capacity, these groups are held together by a shared philosophy, according to Michael Ramos, lodge development manager for the Grand Lodge of California. “Unless they have an identified culture of meaning that they’re cultivating, Grand Lodge won’t even accept the application,” he says.

One of these new lodges is the Thirty-Three, whose primary purpose is philanthropy. Membership is capped at just 33, and members are required to be Grand Master–level donors to the California Masonic Foundation. Dues of $1,200 per year fund an annual $10,000 philanthropic budget, says Art Salazar, the current grand treasurer and founding master of the lodge.

Beyond the focus on charity, the lodge’s members envision a level of grandeur to their meetings, which will take place at various unusual locations, such as Hollywood’s Magic Castle, where its first meeting is tentatively scheduled for spring 2021. However, Salazar stresses that membership in the Thirty-Three is meant to augment Masons’ connections to the fraternity, not replace them. “We’d be sad if one of our members left his home lodge to join us,” Salazar says. A possible rule change may make that kind of dual-lodge membership more feasible: Legislation to be voted on next year would allow lodges to meet less frequently than the currently mandated once per month. The Thirty-Three is among those that would propose meeting quarterly, making the time commitment of its multiple-lodge members far more reasonable. For the moment, that’s beyond the scope of the California Masonic Code. But as everyone knows, rules can change.

Even within the current code, there exist some exceptions to the norm. The Columbia Historic Lodge, also under dispensation, operates as a sort of preservation society, dedicated to the management of the Masonic Hall inside Columbia Historic State Park. Like a research lodge, Columbia Historic does not confer degrees. It meets once a year, during which its membership congregates for a short business session, followed by a celebratory dinner, capping what for many is a family weekend getaway in the Sierra foothills.

IF AFFINITY- STYLE LODGES TAKE HOLD, IT WILL BECOME MORE POSSIBLE—EVEN DESIRABLE—TO AFFILIATE WITH SEVERAL.

Expanding the possibilities for less frequent or quarterly meetings could open the door to all sorts of opportunities for members to affiliate with multiple lodges, including ones like the Thirty-Three that suit a narrowly defined interest.

Hermes Lodge is another such lodge. Unlike the Thirty-Three, the group opted for a permanent home, inside the Long Beach Scottish Rite Temple, where its members are dedicated to the study of esoterica. Joseph Newman, the lodge’s senior warden, is the man behind the Instagram handle @Keepers_of_the_Word, a Masonic esoteric-research group with 35,000 followers. Newman hopes to tap into that rich vein of interest with Hermes Lodge. “We want to craft the experience around the mysticism and magic we think are central to traditional Masonry,” he says.

Donald Joe, junior warden for the lodge, says the Scottish Rite Temple suits that vision. “The extensive library and the overall feel of the temple fit our purpose perfectly.”

Clearly, not every new lodge is for every member. Rather, they aim to be just right for a distinct few. Where the Thirty-Three and Hermes tend toward grand, ornate visions of what a lodge meeting can be, another newly instituted lodge, Palos Verdes, based in Gardena, is taking things in another direction. Its members are aiming for a kid-friendly environment with frequent, casual family gatherings, according to secretary Rene Andalajao.

Newman puts it plainly: “Having a central idea is allowing us to craft a lodge of brothers who all have something in common.”

What he’s describing is essentially the affinity lodge, a common phenomenon in other Masonic jurisdictions, particularly in England. These lodges, which meet infrequently, exist in parallel to home lodges and are built around even narrower areas of interest—things like classic cars or a favorite soccer club. These aren’t neighborhood groups; often members travel a great distance to attend meetings in, say, London once or twice a year. Some notable English affinity lodges include Radio Fraternity No. 8040, whose members are amateur radio operators, and Shotokan Karate No. 9752, whose members practice martial arts.

In the United States, examples are fewer in number, but they’re not unheard of. (In the spring, this magazine featured Maryland’s St. Florian-911 Lodge No. 238, an affinity lodge for firefighters.) Lodges based at a university were common in the mid-20th century, and California includes foreign-language lodges like Maya No. 793 and Panamerican No. 513, both of which work the degrees in Spanish. These aren’t technically affinity lodges, as they hold degree ceremonies and meet monthly; on the other hand, they show that the idea of a themed lodge is one we’re already familiar with.

If affinity-style lodges take hold, it will become more possible—even desirable—to affiliate with several. Future Masons will be able to curate their own Masonic experience by joining up with multiple groups that fit their personality.

Each of these new lodges embodies a well-defined theme and is intended to deepen, not replace, the existing Masonic experience.

What’s missing from the picture is the actual lodge hall. “The days of wanting to—or even being able to—afford real estate are long gone,” Ramos says. Instead, tomorrow’s lodges will choose meeting places that fit their individual needs, whether that’s in an existing hall, a library, or a private club. When the intimate Freemason’s Hall opened inside the California Memorial Masonic Temple in 2019, nine different lodges began sharing the space. None of them is responsible for the administrative burden of managing it. “No one got into Masonry to become a landlord,” Ramos says.

Freed of the need to form hall associations, repair a leaky roof, or find rental tenants, these lodges are able to direct their attention toward richer pursuits, like hosting guest lectures or family picnics or charity drives.

Small and intimate, meaningful and relatable, agile and flexible: Somewhere in this alchemical brew lies the future of California’s Masonic lodges.

What, then, of the 300-plus other lodges in California, many of which proudly own a lodge hall and have histories going back 150 years? Is there room in this vision for the traditional California lodge?

In a word, yes.

Small affinity-style lodges need not replace the state’s existing lodges. In fact, they can enhance them by repositioning them as a parent lodge—the place where degrees are conferred and where Masons come together in large numbers. Says John L. Cooper III, a past grand master who has experienced lodge life in just about every part of the state, “I’ve been the master of five different lodges since 1969. Masonic lodges will continue to evolve, but the suburban model of a lodge involved in its local community will always be important in California Freemasonry.”

By offering tomorrow’s prospects a range of satellite options orbiting around a deeply rooted parent lodge, Ramos says, the fraternity will be positioned to draw in ever-more members, who will see in California Freemasonry an organization suited to their world—rather than their grandparents’. The future may never be completely knowable, but at least one thing is certain: Change—big or small—is here to stay.

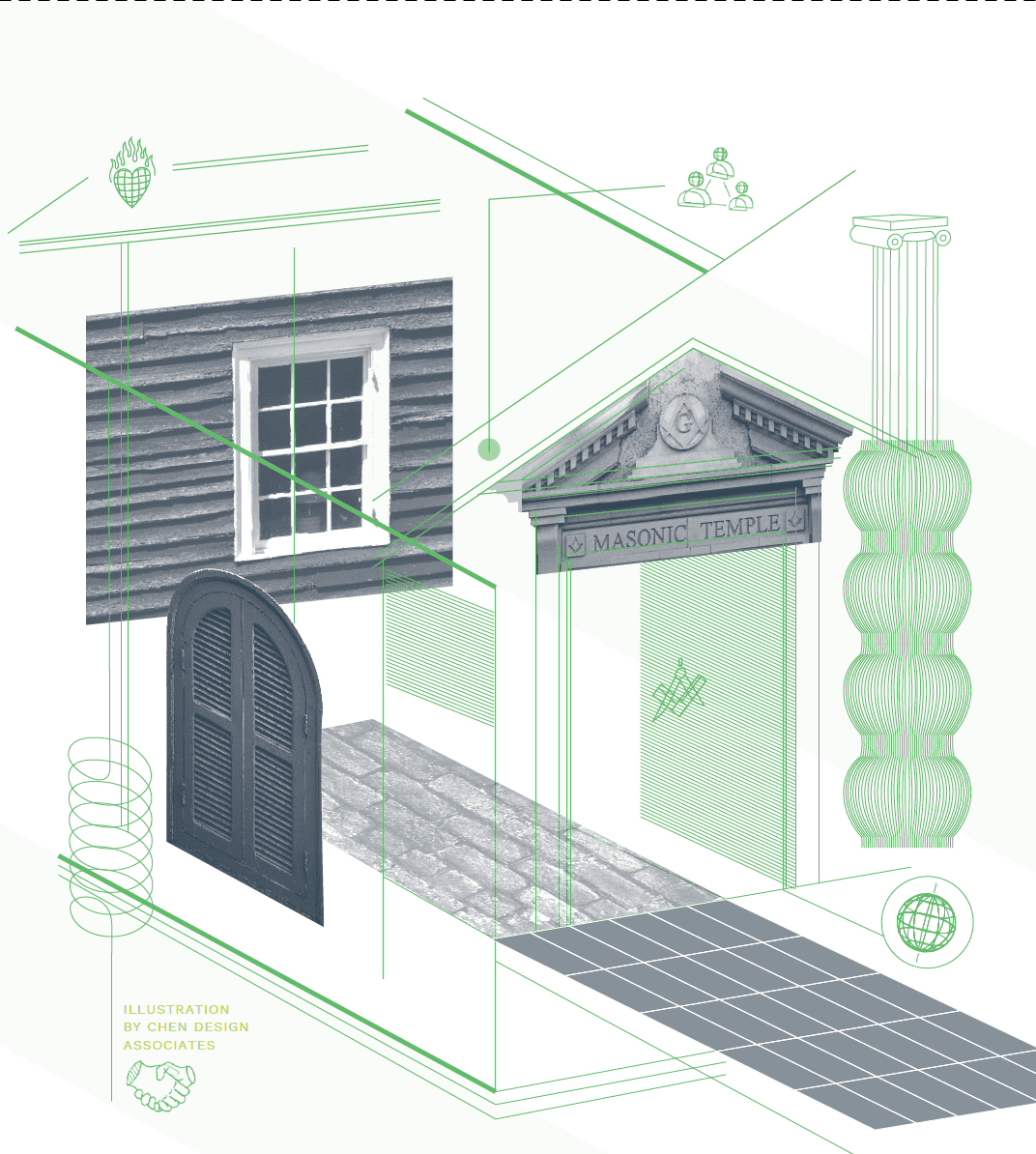

ILLUSTRATION CREDIT:

Chen Design

For a generation of Freemasons, the place to turn for info isn’t in person, but rather online.