Donor Profile: Patrick Muldoon

A bridge-building Bay Area Mason reflects on the importance of charity, giving back, and offering Masonic relief.

California Masonry includes members from just about every country on Earth, especially Latin America. Among them are a great many who belong to, or affiliated from, Masonic lodges abroad. Here, we meet a special group of California Masons with an up-close understanding of Freemasonry in Latin America. —Ian A. Stewart

Oliver Torres: My father was in the military, and the command he belonged to was stationed in the Villa Santa Ines, which was the home of Joaquín Crespo Torres, the former president of Venezuela and sovereign grand commander of the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite in Venezuela. I grew up playing and running around there, and it taught me a lot about Freemasonry. I suspect that my father was a Mason too, but he never told me anything about it. Years later, I joined a military lodge in Caracas, before I came to the United States.

In Venezuela, like all Latin American countries, we celebrate our history with fervor. When you read about the revolution, our leaders were all Masons. Many of our founding fathers, like Simón Bolívar, were Masons, and their speeches are full of Masonic words and ideals. José Antonio Páez, a hero of the revolution, was grand master of Venezuela. Even our flag has Masonic elements— the three colors, the seven five-pointed stars.

For us as Latin Americans, Masonry is more than just a place for fraternity or for becoming better men. It represents a connection to our history and to our family and ancestors. Being a Mason is a way to set an example for your family to follow. It means placing a column of pride that can sustain your family during adversity. Saying that my father or grandfather was a Mason is saying that they were a worthy example to follow.

Edguin Castellanos: Yes, many lodges in Belize were “quasi-Masonic.” My lodge, Star of King David Nº 5, belonged to the Independent United Order of Scottish Mechanics. The degrees are very similar to Masonry, except the symbols are related to mechanics, not stonemasons. We wore the apron and had all the same signs, and most of the rituals were the same. It was popular in the Caribbean and former English colonies, but these days it’s a dying organization. So with some friends from Mexico, which is 20 minutes north, we regularized the lodge to Freemasonry. I was part of that change.

In Belize, we worked in English, so when I came here and joined Panamericana Nº 513, I had to learn the ritual in Spanish, which was challenging. I knew a bit of Spanish, but more like what we’d call “kitchen Spanish”— just enough to get by. It’s also a different ritual. It’s similar, of course, but in terms of execution, it’s a completely different ball game.

In Latin American Freemasonry, there’s a huge emphasis on esoteric work. Here, it’s more philanthropic. In our countries, we invest lots of time in everything spiritual and esoteric. That’s a huge draw there.

Rogerio Gomes: In Brazilian culture, to become a Mason is seen as a way to grow personally, professionally, and as a leader. So people come in looking for that. But then the longer they’re in the lodges, the more they learn about the philosophical teachings and the mystery of Masonry, and that’s what keeps them there. And then of course there was also the Da Vinci Code.

Absolutely. The city I’m from has probably 100 lodges. In general, you can look at someone in Brazil and say, I know this guy’s a Mason because he’ll put three dots in his signature, or because he wears the pin on his jacket. If you’re driving on the road and someone sees your Masonic bumper sticker, they’ll honk their horn three times at you, to say hi. Brazil is very social. People want to make friends, and this is a way to make friends.

Oh yes, to the point that I know of many Catholic priests who are members—people who are very rooted in the diocese. I’d say that in Brazil, most lodges take you on a very spiritual journey to become connected to something even greater than yourself. That attracts a lot of people. And I think Catholicism and the symbols of Masonry have a lot in common.

I’ve been able to visit lodges all over Latin America—Chile, Brazil, Mexico. They work very differently from here. All of them do the work very solemnly. When we’re inside the temple, we sit up straight, legs together, hands on legs. You don’t speak when you’re in lodge. And here, the ritual is done from memory. That’s incredible. In South America and Mexico, too, you read it. Here, you have to have a very good memory to be a Mason.

In South America, we can’t talk once the meeting is open. Being silent, we learn how to have our thoughts together so that when we do get an opportunity to speak, we have something meaningful to share. After the meeting, if a brother wishes to speak, according to their rank, they request permission from their warden.

When you visit a lodge in another country, you really feel the fraternity. I once went to a [table lodge] in Brazil with 300 Freemasons. When I came to the United States, I felt that these were brothers I’d known for years. It was the same feeling.

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF

the subjects

A bridge-building Bay Area Mason reflects on the importance of charity, giving back, and offering Masonic relief.

A history-spanning, forward-looking celebration of the fraternal and cultural connections between California and Mexican Freemasonry.

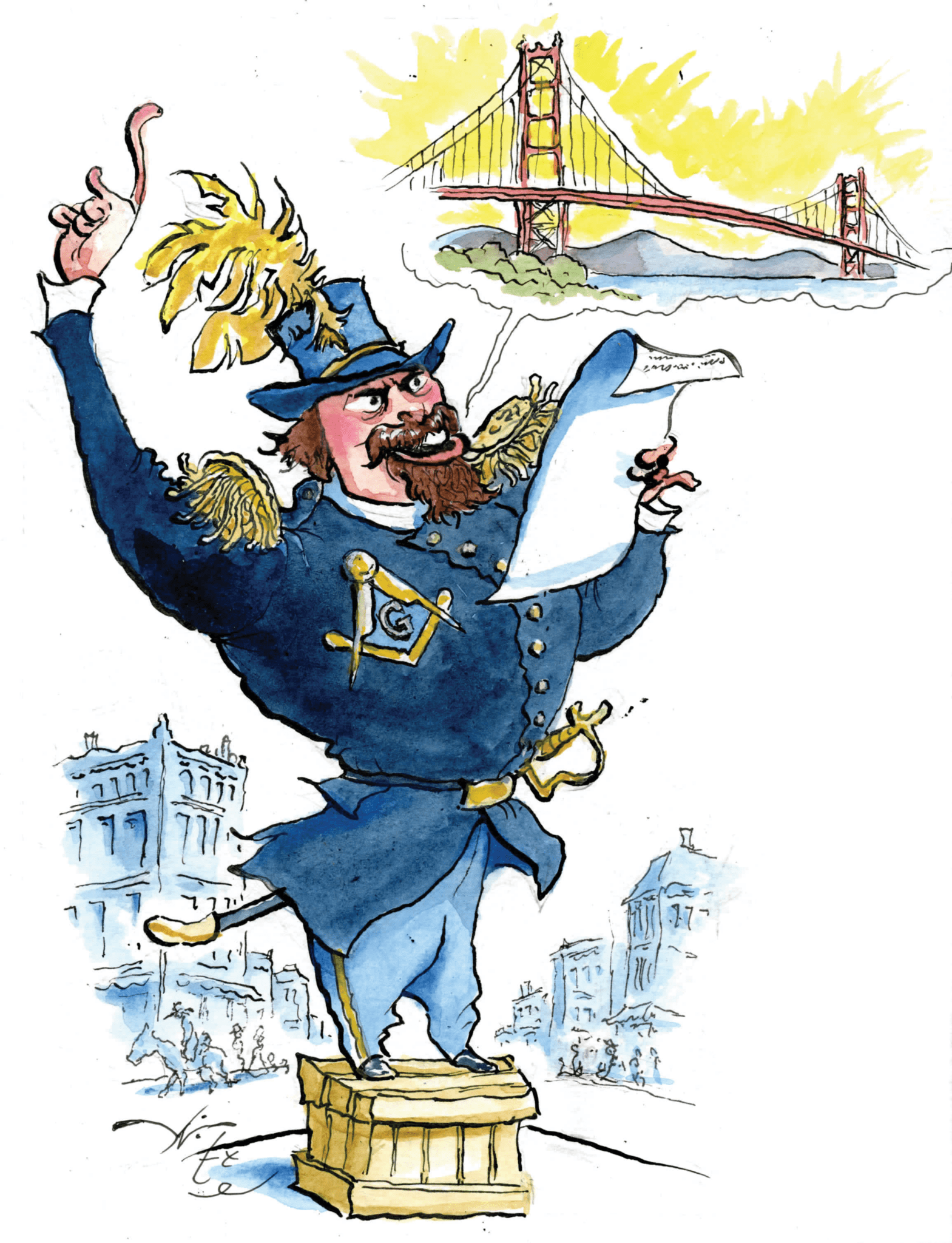

150 years after he first proposed the San Francisco Bay Bridge, the legendary eccentric and Freemason Emperor Norton may finally get his due.