With ‘The Pentaverate,’ Secret Societies Are Suddenly Everywhere on TV

Led by ‘The Pentaverate’ and ‘The Lost Symbol,’ allusions to secret fraternal organizations based on Freemasonry are suddenly everywhere.

Once you begin to see the signs of Brazil’s infatuation with Freemasonry, you can’t stop seeing them. There are the obvious ones, of course. There are the bumper stickers, signet rings, and Masonic lodge banners that are common to just about every part of the country. But look a bit deeper at Brazilian Freemasonry, and you’re overwhelmed with subtle hints of a cultural phenomenon that hasn’t just survived in the seat of South American power, but has thrived.

In Paraty, a Unesco World Heritage site and coastal tourist destination in the state of Rio de Janeiro, the cues are even more prevalent. Constructed by Portuguese Freemasons 250 years ago, the city is like a shrine to Masonry. Streetlights and building columns are engraved with geometric ciphers and painted blue and white. The very layout of the city is a nod Masonic geometry, built on a grid of 33 blocks.

And above the city flies its distinctive and Masonic-inspired flag, featuring three stars set in a triangle.

These days, Brazil increasingly bears the marks of a country where Freemasonry is in the ascent. Whereas worldwide membership in the fraternity has generally been in decline, it has exploded in Brazil. There are more than 6,000 Masonic lodges in Brazil today. In the state of São Paulo alone, there are more than 800 lodges just affiliated with the Grande Oriente do Brasil—the largest of several Masonic governing bodies in the country. (São Paulo and California have similar-sized populations; by comparison, the Grand Lodge of California has just over 330 lodges.) Those numbers keep growing, too. And with them, so too do the outward manifestations of the influence of Freemasonry in Brazil.

It’s not just in cities. Walk through a small town in the countryside and you’re bound to stumble across a Masonic lodge room whose very presence seems to beg the question, How did that get here? Why has Freemasonry spread like wildfire in Brazil but not in, say, Ecuador? Like so much about the country, the answer lies in a complex blend of cultural and historic forces.

Freemasonry has played a key role in Brazil’s history. The first emperor of the republic, Dom Pedro I, was a committed Mason who, upon declaring independence from Portugal in 1822, named his advisor and fellow Mason, José Bonifácio, the first grand master of the Grand Oriente do Brasil.

The connection was fundamental to 19th century Brazil, says Monica Dantas, an associate professor at the Universidade de São Paulo and an expert on fraternalism in South America. Masonic lodges were a “privileged space,” she says, where Brazil’s founding fathers could “formulate a strategy for independence without being in the public eye.” In the absence of political parties or a robust university system, lodges acted as an important vehicle for spreading new political thought—including the abolition of slavery.

That history still looms large in Brazil, which this year will celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Grande Oriente. And unlike in many other countries, discretion has not necessarily been part of the equation. Members proudly display their lodge affiliation and often go to lengths to acknowledge one another in public. Masonry in Brazil, in other words, is hard to miss. In fact, the current vice president, Hamilton Mourão, recently appeared on the country’s largest TV network to talk about Masonry. (A clip showed him at his lodge; when he appeared in studio, the house band welcomed him with a Masonic anthem.)

Growth has been a major trend in Brazilian Masonry, particularly in the 21st century. The economic boom years of the early 2000s were crucial to that expansion.

According to the World Bank, the size of Brazil’s middle class more than doubled in the space of a decade. At the same time, interest spiked in Freemasonry. From 2003 to 2009, the Grande Oriente do Brasil (GOB) added nearly 500 lodges and 14,000 members. By 2013, between the national and state grand lodges, there were more than 213,000 Masons in Brazil spread across 6,500 lodges, making it one of the largest Masonic populations in the world. The bicentennial celebrations being held in each state have brought even more attention to the fraternity. According to Gerald Koppe Jr., the deputy grand chancellor of foreign Masonic relations for the GOB, that membership growth has brought the average age of Brazil’s Masons down dramatically. Today, he says, the median age of new members is 28. “We’re initiating a lot of 20- and 21-year-olds, and we receive a lot of college students through outreach work with the universities,” he says. Additionally, Masonry is popular among the members of Brazil’s armed forces, further skewing its membership’s age downward.

However, demographic trends can’t fully explain the growth of Freemasonry in Brazil. For many, the answer lies in its members’ ability to marry Masonic brotherhood with the Brazilian thirst for social life. That, says one member, explains the growing number of lodges in small towns, where Masonry can foster community networks and structure that are otherwise lacking. “People are proud of being known as a Mason,” he offers. “It’s a real badge of honor.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

LOU FERNANCO/CC-ALAMY

Led by ‘The Pentaverate’ and ‘The Lost Symbol,’ allusions to secret fraternal organizations based on Freemasonry are suddenly everywhere.

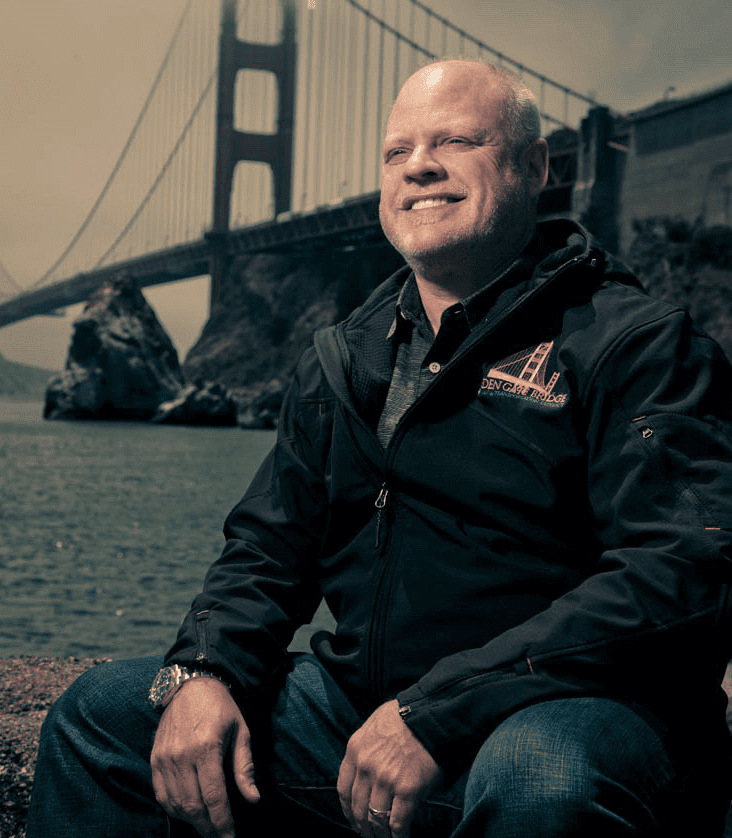

A bridge-building Bay Area Mason reflects on the importance of charity, giving back, and offering Masonic relief.

A history-spanning, forward-looking celebration of the fraternal and cultural connections between California and Mexican Freemasonry.