Outstanding in Outreach

How Beach Cities No. 753 made lodge outreach central to its entire mission.

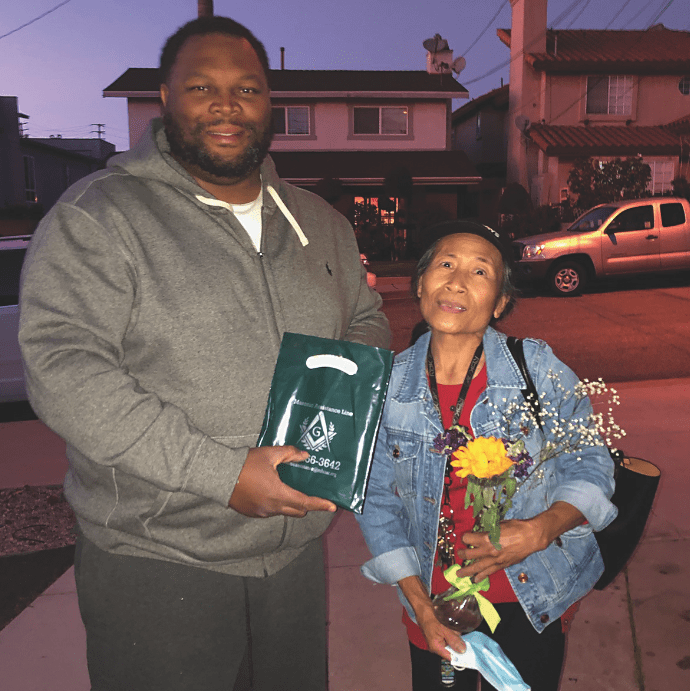

Perched behind the 1927 Estey pipe organ inside the Oakland Scottish Rite Temple, Michael Solomon has witnessed hundreds of Masonic degree conferrals. And while the individual details have largely become a blur in his mind, it’s safe to assume that his part in those rituals has left a distinct imprint on each candidate’s memory of the event.

As the lodge organist for Live Oak No. 61 and Templum Rosae No. 863, both in Oakland, Solomon has a unique perspective on Freemasonry. The melodies he plays during Masonic events are a key aspect of the lodge experience. More than any other member, he is responsible for creating the right atmosphere, from strictly-business meetings to solemn funeral services to reverential degree ceremonies. It’s no surprise, then, that the organist is recognized with a formal lodge officer title.

And yet, for all the responsibility the organist is afforded, Solomon is one of the last of a vanishing breed. Of the more than 330 Masonic lodges in California, only a quarter have an appointed lodge organist. Of those, it’s estimated that perhaps 10 percent actually play an electric or pipe organ—the rest play the piano, another instrument, or serve as something more akin to a director of music. That’s reflected nationally, as the ranks of organists of all stripes have been dwindling for years. One oft-cited reason is the decline in attendance at church—where most organists are first introduced to the instrument. Because of their tremendous size and cost to repair, pipe organs are becoming increasingly rare. Unsurprisingly, in 2015, the American Guild of Organists reported an expected drop in its membership of 25 percent over the next decade.

For Masonic lodges, that represents a real loss. With its otherworldly tones, the pipe organ enhances the ritual like no other instrument can. Dubbed “the king of the instruments,” a pipe organ can rumble, bellow, chill, or thrill, and its notes match every octave of the human vocal range. Often associated with religious ceremonies, the organ has for centuries been the instrument of choice to tap into the ethereal. It’s no wonder, then, that Freemasonry places the organ on such a pedestal. “Music is not merely an adjunct to the body of Freemasonry, simply providing entertainment away from its rituals, but a vehicle to increase understanding,” writes Merrick Rees Hamer, the organist and a past master at Culver City–Foshay No. 467. “The power of intonation is entrancing and prepares the mind for focus.” Hamer marvels at the physical sensation of feeling the sound waves emitted from a powerful pipe organ reverberate in your chest.

Above:

Michael Solomon plays the Oakland Scottish Rite Temple’s 1927 Estey pipe organ.

Gary Sponholtz, a well-regarded organist in the Bay Area (though not a Mason), puts it this way. “Pipe organs breathe. They’re a living instrument. The way the air and the sound come at you, it’s a physical thing. It’s a different kind of a sound wave.”

And to be sure, the Masonic ritual experience is largely sensory. During the memory portion of a candidate’s degree proficiency, he relies on location, feeling, touch, sights, and sound as a way of meditating on his journey. The duty of the organist, then, is to evoke a feeling of magic. Says Cactus Sam Harris, a musician, instructor, and lodge organist with Fresno No. 247, “Music and motion create emotion. If I play it a little mysteriously, I invoke curiosity. ” Harris, who is also director of music and arts at University Presbyterian Church in Fresno, first learned the organ in high school, when Cal Poly offered the public the opportunity to play their newly built $2 million concert pipe organ. At his lodge, he plays a Hammond organ. Clay Couri, who has previously served as lodge organist for Carmel No. 680, was for many years music director at St. John’s Chapel in Monterey, where he played a Reuter pipe organ. (His lodge has a piano.) “As an organist, you’re the conductor and every musician of the orchestra,” he says.

Solomon, who is also a piano and guitar instructor, recording artist, and record producer, agrees with that sentiment and sees in the pipe organ a musical parallel to the symbolism of Freemasonry. “It’s sonic architecture,” he says of the instrument.

There are no particular mandated organ songs for a Masonic lodge. Unlike ritual work, which is carefully overseen by a district inspector, the organist has free reign to play whatever he feels will set the right mood. Common lodge songs include Pleyel’s Hymn, Mendelssohn’s March of the Priests, the marches from the opera Aida or The Prince of Denmark, Symphony No. 9 From the New World by Dvorak, and various hymns and theatrical works.

Larry Boysen, an organist with two San Francisco lodges, injects a bit of humor and improvisation in his selections, such as when a meeting runs long or needs livening up. On those occasions, he’ll sneak in a quick jingle—favorite soundbite pranks include the old silent-film chestnut “Hearts and Flowers” and the theme from The Mickey Mouse Club. “I’m like a silent movie background,” he says. At both Pacific Starr King No. 136 and Golden Gate Speranza No. 30, he plays electric organs. (At the former, an Allen; at the latter, a Conn.)

While they may be a small tribe today, California’s Masonic organists continue to fulfill an important role. In addition to serving as the fraternity’s grand organist, Steve Miller is also the organist for the Pasadena Scottish Rite, which features an incredible circa-1934 pipe organ. Miller says he takes pride in creating memories by providing a meaningful soundtrack for what is, after all, a deeply profound ritual experience for new members of the fraternity.

“This is what we do,” Miller says of the organist’s role. “We make it a wonderful place to be a part of. We change people’s lives for the better.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Peter Prato

How Beach Cities No. 753 made lodge outreach central to its entire mission.

Grand Master Jeffery Wilkins explains how music deepens the magic of Masonry.