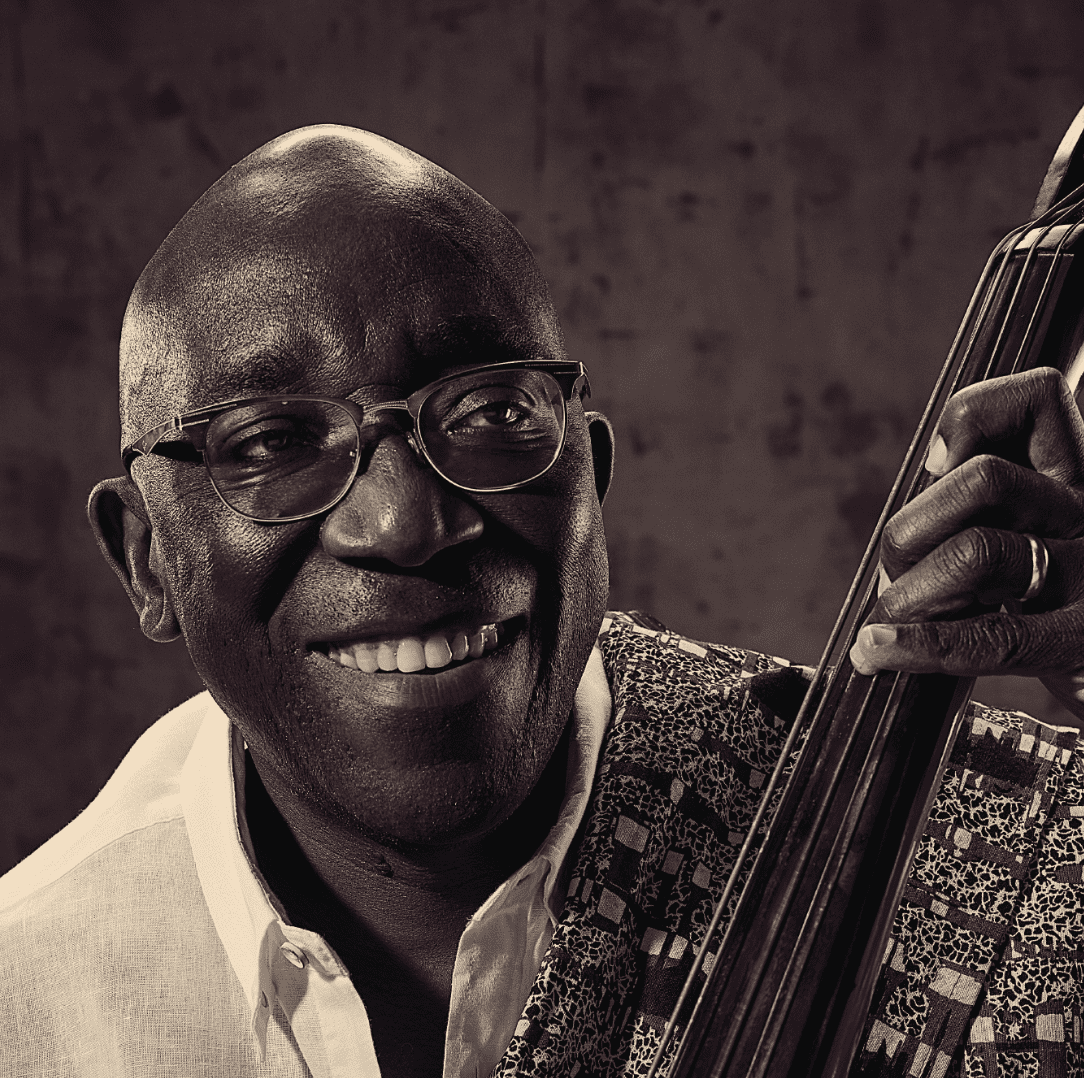

He has performed some of the most celebrated roles in opera: Ferrando in Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte, Mack the Knife in The Threepenny Opera, Paolino in Domenico’s Secret Marriage. But for Terence Trevor Lopez Panganiban, there’s a part out there he was practically born to play—one that represents a glorious melding of three important elements of his life. It’s the role of Ibarra, the hero of Felipe Padilla de León’s Noli Me Tangere, the first all-Tagalog opera composed in the Western tradition. The story is based on the writings of José Rizal, the profoundly influential 19th-century Philippine independence hero, martyr, and Freemason.

It’s easy to understand the appeal for Panganiban, whose pride in his heritage and affinity for Masonry are personified in Ibarra. It’s also a tidy encapsulation of the East-meets-West alchemy that distinguishes so much of the culture of the Philippines—and which Panganiban celebrates through his work.

It wouldn’t be the first time Panganiban’s Masonic and professional worlds have collided. Offstage, prior to a performance in Manila several years ago, Panganiban was introduced to the pianist Nathaniel Silva, a member of Gardena Moneta No. 372, where Silva is the lodge organist. Four years later, it was a connection of Silva’s, Jovi Rivera, who invited Panganiban to perform at Torrance University No. 394’s America’s Got Talent–style concert. Panganiban, whose father had been a grand lodge officer in the Philippines, knew he’d found kindred spirits among the musical Masons, and in 2012 he petitioned to join the lodge.

Since then, Panganiban’s voice has been a staple at Masonic gatherings. By his estimation, he’s performed during at least 20 officer installations, and in 2014 he was invited to sing Andrea Boccelli’s “Because We Believe” at then-Grand Master John Cooper’s banquet. “My whole family came from the Philippines,” Panganiban says. “It was a way of saying thank you to Filipino Americans for sending so much relief back home.”

The performance was a success, and two years later, Panganiban was invited to sing an aria from Mozart’s famous Masonic opera, The Magic Flute.

Panganiban has found success as a performer outside Masonry, as well. As an undergraduate at Manila’s Santo Tomas University, he was a featured soloist with the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra. After relocating to the United States (his mother is American, and the family lived in Southern California off and on during Panganiban’s youth), Panganiban joined the Land of Enchantment Opera in Gallup, New Mexico, and performed with the Taos Opera Institute—all while receiving a master’s degree at Cal State Fullerton.

Panganiban has been something of a trailblazer as a Filipino American vocalist. Opera was first introduced to the Philippines in the 19th century, and while the major companies there still mainly perform the canonical works from European composers like Puccini and Verdi, the islands have developed a distinct local take on the form. That heritage can be seen in the Philippine sarswela, a short operetta that blends singing and folk dancing. In form and name, it’s adapted from the Spanish zarzuela, a style seldom seen in the United States. “Our training growing up was more of what you’d call bel canto, or ‘beautiful singing,’” he says—a centuries-old technique.

Though Filipinos are still relatively uncommon among the upper echelon of opera performers, a small number have started to break through. Panganiban points to the tenors Noel Velasco and Arthur Espiritu, the first Filipino to sing at the famed La Scala in Milan. Now a new generation of Filipino and Filipino American performers arebreaking through. “It’s getting more diverse,” Panganiban says of the opera world. “But it’s really competitive. It’s a lot of behind-the-scenes work in the choir before we ever hear from most performers. But we’re getting there.”

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Moonbeam Studios/Russ Hennings

More from this issue:

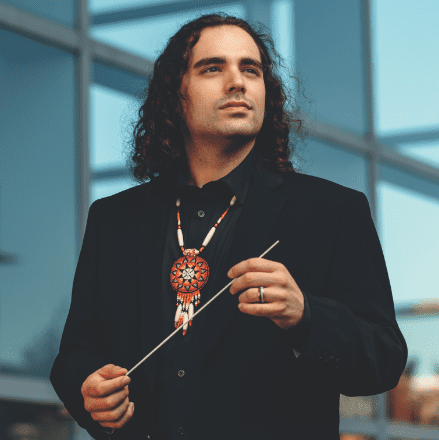

Member Profile: Austin Davis

A Mason and conductor putting Native American music on the map.

Executive Message: Sounds of Harmony

Grand Master Jeffery Wilkins explains how music deepens the magic of Masonry.