Friends of Friends: Meet the Masons Extending Our Reach

Meet the California Masons putting Masonic philanthropy into practice through like-minded community organizations.

By Ian A. Stewart

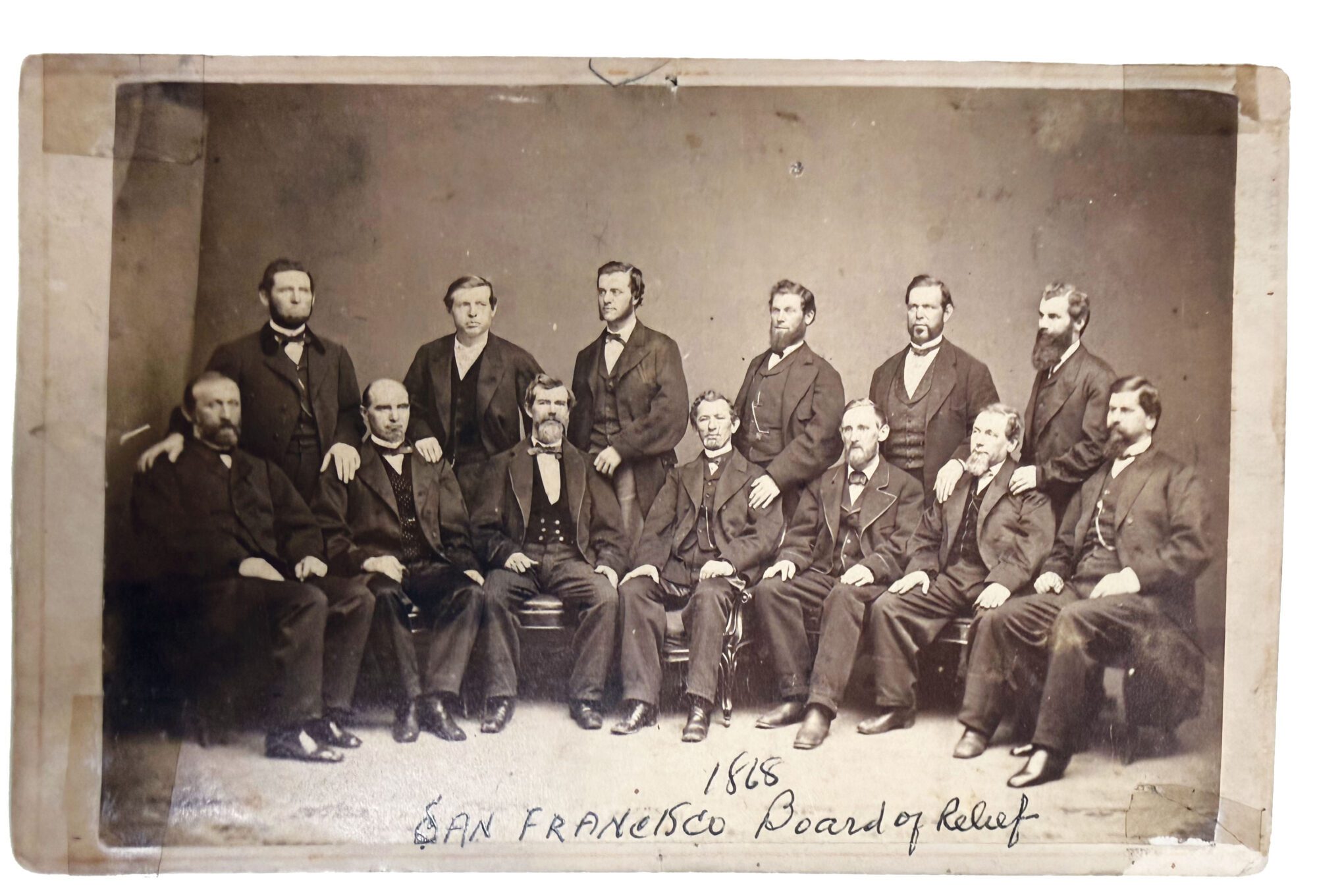

Above: The San Francisco Masonic Board of Relief in the wake of the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The year was 1924, and Mary Travis was on her own. After her late husband died back in Alabama, she’d moved to Oakland to help take care of her three grandchildren, whose mother had also passed away. Their father had left town, leaving her to care for the children with no income and a paltry savings. Things like social security, government-supported health care, and unemployment benefits did not yet exist. So Travis did what many widows in her position did: She talked to the Masonic relief board.

For more than 100 years, Masonic lodges in California and around the globe were often the first point of contact for members and their families who’d fallen on hard times, whether due to illness or injury, death, or disasters like earthquake, fire, or flood. In response, those lodges organized local relief boards that received applications and disbursed charity dollars, often to Masons from out of town (known as “sojourners”). For much of the 19th and early-20th centuries, this form of Masonic relief was one of the most visible and practical benefits of membership in the worldwide fraternity.

In California, that tradition started early. The state’s first board of relief was organized in San Francisco in 1856, in response to overwhelming demand for charity lodges experienced in the wake of the great cholera outbreak of 1850–52. The relief board, made up of members from each of the city’s 10 lodges, allowed the fraternity to formalize charitable disbursements, avoid duplicate requests, and identify scam artists—of which there were many. Fifty years later, in 1906, the San Francisco board organized the most dramatic relief effort in its history following the massive earthquake and fire that displaced half the city’s residents. Summarizing its actions a year later, Motley Hewes Flint, Grand Master at the time, recorded more than $225,000 flowing through the relief board toward Masons (and others) in need.

In addition to direct funds, Masonic relief also encompassed many other forms of assistance. For instance, Masons were frequently able to connect those in need with members who worked as doctors (who would often offer discounts to such referrals), lawyers (paid for through a Masonic legal defense fund), or other similar professions. In fact, one of the most common acts of the relief board in its early years was organizing and paying for a Masonic funeral service: The Los Angeles Board of Relief at one point purchased an entire cemetery in Glendale for that purpose.

The L.A. relief board, organized in 1881, would quickly grow to become the largest in the state. During the 1920s, boards were launched in San Jose, Bakersfield, Sacramento, Stockton, Oakland, San Diego, Fresno, Long Beach, and Honolulu, then part of the Grand Lodge of California. In 1923, those boards issued more than $100,000 in direct relief.

Beyond that, the relief boards also organized employment bureaus to help out-of-work members connect to jobs—a significant help during the Great Depression, when the unemployment rate spiked as high as 30 percent. “The only practical help that one man may give to another is by placing him in a position to help himself,” wrote Samuel E. Burke, future grand master and head of the Los Angeles Employment Bureau, in 1920. “The handing out of a paltry dollar may tide over the needs of an hour, but that is all. It is not the truest charity, nor, in fact, is it what the man himself usually desires. What he really wants is a job, a chance to work, establish himself, and thereby better his condition.”

In 1926, the Grand Lodge of California for the first time attempted to organize the local relief efforts, creating a Board of Control to offer guidance and collect reports from the many boards, which were rebranded as “service bureaus.”

At the same time, Masonic relief was being formalized outside California. The nationwide Masonic Relief Association of the United States served as a clearinghouse for state and local boards, ensuring that assistance provided to a sojourning member in one state would be refunded by Masons from his home state. In 1919, the Masonic Service Association was formed to coordinate Masonic relief sent to overseas troops.

During that period, providing Masonic relief became one of the most important undertakings of the state fraternity. In 1941, a high of 18,368 Masons found work through Masonic employment bureaus, at a nominal cost of $1.76 per placement. By 1965—when membership in California reached its peak—the state included 20 local service bureaus, which together staged 1,141 funerals, made 35,001 calls to the sick or distressed, conducted 2,302 investigations into sojourning Masons’ well-being, and collected donations of 4,397 units of blood from California Masons.

Of course, those statistics tend to obscure the specific distress that individual members faced. For instance, in 1921, Hazel LaFerrier approached the L.A. board after her husband had been convicted of larceny and sent to jail, leaving her penniless with their three children. The board provided them with food and clothing and arranged for her to return to her family in Wisconsin. Or James Johnson, a Mason from Washington State who in 1919 approached the L.A. board because he’d been permanently disabled and his wife had developed cancer. The Masons arranged for a nurse for his wife and eventually covered her funeral expenses. And in perhaps the most famous case of Masonic relief, in 1878 a four-year-old orphaned boy, Walter Wilcox, became a media sensation when the Grand Lodge of California offered to make him a ward of the fraternity. Grand Treasurer Nathan Spaulding, a former mayor of Oakland, eventually adopted the boy, who went on to join Oakland № 188.

As the fraternity began to contract in the late 1960s, so too did its statewide relief program. In 1967, the Board of Control recommended shuttering the local employment bureaus, as other government and nonprofit organizations had begun offering similar services. In time, other supports were subsumed by private benefits and public-sector programs. In the early 1990s, as many of the old boards were closed, the remaining Masonic Service Bureaus came under the control of the Grand Lodge of California. Today, the only one in operation is the L.A. Masonic Service Bureau, still funded primarily through a large bequest made in 1906 by State Sen. Charles W. Bush.

At the same time, the Masonic Homes of California stepped in to fill the void left by those closures. The opening of the Covina campus to seniors in the 1970s provided elderly Masons in Southern California with housing and health supports, as the Union City location in Northern California had since the 1890s. In the 2000s, the Masonic Homes’ “non-resident fund,” used to support seniors who were otherwise ineligible or unable to move into a campus apartment, was redesigned as Masonic Outreach Services, providing funds, case management, and other types of support for seniors around the state. In 2009, MOS developed Masonic Family Outreach Services to work with Masons under 60.

Today MOS provides case management or financial support to about 500 Masons and their families each year, at a cost of nearly $3 million. And the legacy of the old Masonic boards of relief lives on through its lodge outreach program, which trains members to contact and connect elderly and distressed members in their towns to public benefits and Masonic supports.

Although the once-robust network of Masonic boards of relief is no longer a feature of California’s fraternal life, the spirit behind them remains integral to Freemasonry. “Both in concept and performance,” Grand Master Laurence E. Dayton wrote in 1967, such relief “exemplified the finest traditions of our craft and established an imposing record of service.”

Photography by:

Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

Meet the California Masons putting Masonic philanthropy into practice through like-minded community organizations.

Meet a Darryl Watts, member of Elk Grove No. 173, who helped organize a 3,000-pound donation with fellow community organizations.

Meet one of the state’s top Masonic ritualists, who says Masonic philanthropy is the key that unlocks it all.