The Common Denominator

Examining the divisive issue of religion that's unified the fraternity.

By Laura Normand

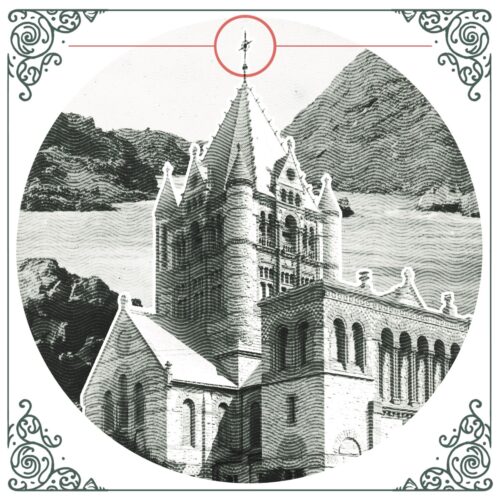

Below is the article from the September/August 2012 issue of California Freemason. Read the full issue here.

The topic of religion in Freemasonry is a coin with two sides: On one, open acceptance of differences in worship. On the other, faith-based membership requirements and rituals. In trying to reconcile this yin and yang – the pushing out of religious differences alongside the pulling in of so many faith elements – controversial questions emerge. This much is certain: Without its policy of religious tolerance, Freemasonry could not have succeeded in creating a new social space. Without its grounding in faith, it would be a different organization altogether.

The Shift From Christianity

Europe in the 16th century was a predictable place, faith-wise. Unless you were one of a small number of Jews – who, often, hid their heritage for fear of expulsion – your rulers and your neighbors believed in a Christian God, you believed in a Christian God, and it may never have occurred to you that, elsewhere in the world, another person might not.

And so, in the first recorded Charge of an operative Freemason in 1583, with the Church of England as the official religion in that country, it should come as no surprise that God is Christian and that members must swear to worship Him as such.

“That ye shall be true men to God and Holy Church,” the Charge reads, “and you shall use no error nor heresy by your understanding or discretion but be ye discreet men or wise men in each thing.”

As Robert Peter writes in “Freemasonry and Natural Religion” (published in 2000 in Freemasonry Today magazine), “the Old Charges have almost without exception a positively Christian character.” All but one of the Charges began with a prayer to the Holy Trinity.

But between 1538 and the printing of Anderson’s Constitutions in 1723, a lot had changed. This was the beginning of the Enlightenment, after all, when new ideas were being stoked throughout Europe. Religious wars between Catholics and Protestants had torn apart the Continent.

Freemasonry, meanwhile, had evolved from a labor guild into a speculative fraternity, a brotherhood in contrast with the religious and political turmoil of years past. And when James Anderson was asked to set down rules to govern the new society, he left a man’s faith open to interpretation.

As the First Charge, “Concerning God and Religion,” goes: “But though in ancient Times Masons were charg’d in every Country to be of the Religion of that Country or Nation, ’tis now thought more expedient to oblige them [Masons] to that Religion in which all Men agree, leaving the particular Opinions to themselves; that is, to be good Men and true, or Men of Honour and Honesty, by whatever Denominations or Persuasions they may be distinguish’d…”

In other words, the fraternity would not be divided by religious differences.

Christian Context

In medieval Europe, when a group of stonemasons decided to form a fraternity, the Catholic Church was a way of life – mandated by monarchs. Even a few centuries later, as operative Masonry gave way to speculative Masonry, Christianity was still the norm in Europe.

It’s no wonder that many elements of Masonic ritual have a Christian influence. To demonstrate the seriousness of their commitment to their brothers and their fraternity, early Masons would have relied on what they knew best: the Bible.

Here are a few examples.

KING SOLOMON’S TEMPLE: In Masonic ritual, the building of the temple plays an important role. Three different books of the Old Testament refer to the building of the temple.

SYMBOLS: The Ark of the Covenant, the mosaic pavement, Jacob’s ladder, the lambskin apron, and many other symbols appear in the Bible.

CHARACTERS: King Solomon, Hiram Abif, Hiram of Tyre, St. John the Baptist, St. John the Evangelist, and Jacob are all biblical characters.

RITUAL VERSES: The three verses spoken in the three Masonic degrees are direct quotes from the Bible.

AND 94 PAGES MORE: Lodges in predominantly Christian communities often present the new Master Mason with a commemorative heirloom Bible, which includes a 94-page glossary of biblical references relating to Masonic ceremonies.

"Good Men and True, By Whatever Denominations"

Anderson’s careful language started a new chapter in Freemasonry. It effectively opened the fraternity to men of any faith. It established a culture of religious tolerance that, today, is so ingrained in Masonry that we cannot imagine the fraternity without it. But at the time, it was radical.

In fact, David Hackett, religious historian and author of the upcoming book “Freemasonry and American Religious History” (to be published in summer 2012 by Princeton), proposes that Anderson’s First Charge may not have been meant to be so radical – not at first, at least.

“The original idea of Freemasonry was to span Christianity,” Hackett says. “Freemasonry was meant to be cross-denominational across Unitarians, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians.” (As a Presbyterian minister, Anderson himself was a “Dissenter,” separated from the Church of England.)

Whatever the intentions, the expanded membership requirements drew the first Jew to the fraternity by 1732. It was only a matter of time before the fraternity became known as a haven for all good men, of any creed. And that drew some unwanted attention.

To Conciliate True Friendship

Careful readers of California Freemason will recall past articles exploring the persecution of Freemasons (see “Freemasonry Confidential,” Jun/Jul 2011). Almost every instance of persecution can be traced to the fraternity’s policy – or lack thereof – regarding religion.

By openly accepting, and thereby, validating, different religions beliefs, the fraternity placed itself at odds with the dominant religious ethos at the time, the Catholic Church. In 1738, a Papal Bull from Rome announced that attending a Masonic lodge would be punishable by death. A wave of similar denouncements swept across Europe. Switzerland, Poland, and Sweden forbade Freemasonry on penalty of death. Lodges were closed in the Netherlands, and in Spain and Portugal. Masonic libraries in Russia were shuttered, and influential Freemasons were expelled or imprisoned.

Yet even as Freemasonry was driven further underground, new members continued to join – with perhaps greater motivation to guard the secrets of their brothers.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the new colonies were forming, many under the leadership of men who were Masons. Individuals who might otherwise have remained “at a perpetual distance” were bound together. And the colonies reaped the benefits.

“Freemasonry was the first group to form organizations that involved community leaders from different religious backgrounds,” says Hackett. “It was foundational to American society.”

“In understanding America as a place that brings together people from different ethnic and religious backgrounds to form a new entity,” he adds, “Freemasonry led the way.”

Questions About Church and Lodge

A lot has changed since then. Wars have been fought; cultures have overlapped; and modern media makes even secret fraternities not so secret any more. But by and large, society has not lost its suspicion about how to characterize the Freemasons. Tough questions remain.

As a former grand chaplain of the Grand Lodge of California, Robert Winterton has heard most of them: Isn’t Freemasonry a religion? What about your rituals? Don’t Freemasons worship a Great Architect of the Universe?

And looming in the subtext: If you’re not a religion, why all the pretense?

Winterton has been the pastor of six Baptist churches, and the senior pastor in El Cajon’s Trinity Baptist Church for the past 43 years. He’s seen many church parishioners join the lodge, and just as many lodge members join the church. He’s also seen how divisive the topic of Freemasonry and religion can be.

“Every once in awhile, a couple will come to the church and love it. They’ll get involved in everything. Then all of a sudden, they discover that I’m a Mason, and they leave the church.” Winterton repeats this softly. “They leave the church.”

Answering for the Fraternity

Hackett points out that “Although Freemasons rarely claimed that their fraternity was a religion, many – both within and outside the fraternity – recognized the brotherhood’s religious character.”

“Most religions talk about practices, rituals, some coming together to affirm common beliefs. So if you have a belief in a Supreme Being and you participate in rituals, then on the outside looking in, Freemasonry starts looking like a religion,” Hackett says.

Here is where non-members – and occasionally members – conflate the two. In its titles, symbols, and ritual, the fraternity is saturated with religious references (see sidebar, “Christian context”). But upon closer inspection, these are signs of the times in which the fraternity was created. And they’re not all that unusual.

“Somebody says, you have to be a religion, you have an altar, you have a Bible, you have a chaplain, you have a funeral service,”” Winterton says. “My answer to that is, so does the Marine Corps.

“Others say, you have deacons, you must be a religion. My answer to that is, deacon is from the Greek diakonos, meaning laborer, or servant. That’s precisely what the deacons are. They serve in a church, and they serve in the lodge,” he continues.

“Isn’t it true that members put Masonry above their families and their religion and their nation, they ask?” Here, Winterton pauses for emphasis. “The answer is no. Specifically not. Your membership is not supposed to interfere with your family, religion, or nation.”

Masonry as a Religion?

To have a frank discussion on Freemasonry and religion, it is wise to acknowledge straight out: Everyone interprets religion differently. Even the word can mean two different things to two different people; to one, religion is a loose spiritual awareness; to another, it is a set of well-defined doctrines. (Hackett confides that even the academic world has yet to agree on its own working definition.) So it’s difficult to tackle without a language barrier, of sorts.

Most of the time, because of its cross-denominational underpinnings, Freemasonry actually uses this to its advantage. Members can interpret the fraternity’s teachings within the context of their own religious experiences, and more often than not, it enriches these experiences.

But on the question of whether or not Freemasonry is itself a religion, the topic becomes murky. Both Hackett and Winterton acknowledge that, at the very least, it was never meant to be. And for his part, Winterton warns Masons against using the fraternity as a substitute for religion. Yet with a membership in the millions, Freemasonry is seen through almost as many prisms.

When I interviewed Hackett, he was insistent on this point. “All Masons are given these beliefs and practices and they interpret them as they wish,” he told me. “Over the course of history, you can always find Masons who claim that Freemasonry is a religion; the handmaid of religion; or not a religion at all.”

Winterton seconds this observation. “Anything that is practiced with great regularity can be a kind of religious practice,” he says. “And some Masons say, well Masonry is my religion; I don’t need another one. Those are the members I invite to church,” he adds.

“We talk about the hereafter in our ritual,” Winterton says firmly, “and we tell a man to seek a relationship with God – but not through Masonry.”

This is the undeniable difference between Freemasonry and religions: Freemasonry has no specific religious requirements, nor does it teach specific religious beliefs. In a Masonic lodge, you don’t proselytize your religion. You don’t even discuss it.

Belief in a Supreme Being

Every young initiate in the Boy Scouts of America takes an oath: “On my honor,” it begins, “I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country and to obey the Scout Law…” The Scout Law requires a scout to be “reverent toward God” and “faithful in his religious duties.” Scouts even earn religious emblems by participating in special church programs.

So while Freemasonry may have been the first organization to require belief in a Supreme Being, it wasn’t the last. Yet the fraternity’s faith requirement still raises eyebrows. As recently as 2009, the subject captivated the masses in Dan Brown’s bestselling thriller “The Lost Symbol.” For centuries before that, it stoked persecution and conspiracy theories.

The question has always been, if Freemasonry is not a religion – or at any rate, isn’t intended to be – why does it require its members to believe in a Supreme Being?

The academic and the spiritual leader offer two versions.

Hackett points to historical context and what looks an awful lot like pragmatism by the fraternity’s leaders: “Prior to 1700 people always believed in God because there was no other way to think of it. Belief in God was part of reality,” he says. “After that? By emphasizing belief in a Supreme Being but not particular boundaries, it allowed Freemasons to form a unity. That’s hugely powerful.”

From inside both lodge and church, Winterton sees it a little differently.

“If you do not believe in a Supreme Being and a life hereafter, your promise is not as strong as someone who believes he will answer for his activities in a later life, and to a higher authority,” he says.

“You don’t have to identify who your God is,” Winterton says. “But for those who believe in a Supreme Being and take an obligation on the Holy Writings, it means more.”

There’s another piece to this. If you believe in a Supreme Being, you recognize a certain code of ethics – one that it is not of mortal mold. Every Mason acknowledges that this code exists, and that it is bigger than his individual beliefs. He strives to conduct himself by its standards, timeless and true. And no matter what iteration of God he worships, he swears his obligations on it.

That’s why, whether in the aftermath of a bloody Papal Bull, the shifting terrain of a young United States, or the modern trappings of present-day California, when a Mason sees a square and compass on the wall, he knows the men gathered there share his code. He knows he can trust them.

Wherever in the world, he is among brothers.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS:

Courtesy of Henry W. Coil Library & Museum of Freemasonry

Wikipedia