At Fidelity No. 120, a Fraternal Home for San Francisco’s Jewish Masons

For more than a century, Fidelity No. 120 was home to a robust Jewish membership.

By Ian A. Stewart

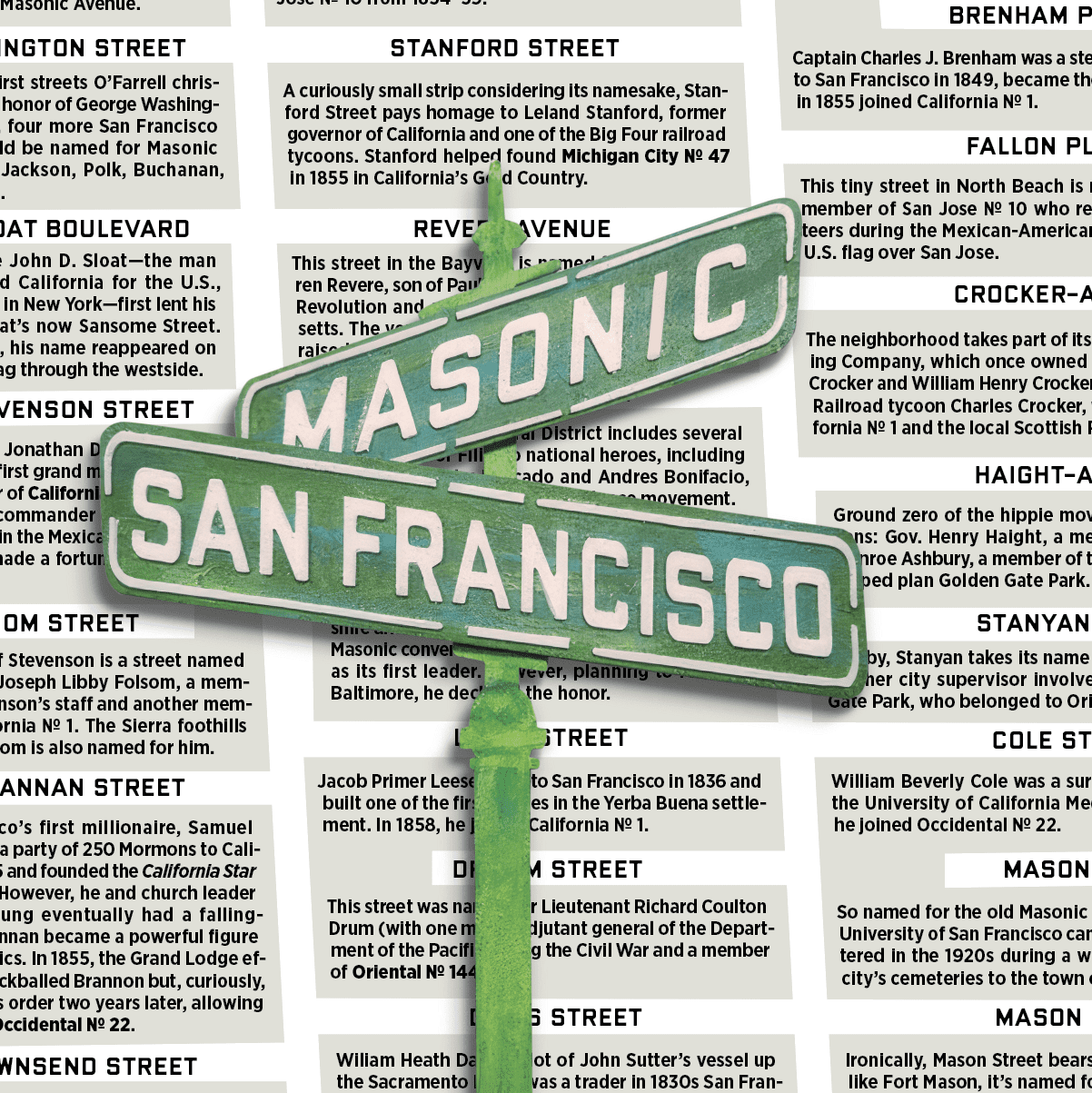

In 1847, the Irish-born land surveyor Jasper O’Farrell set out to redraw the map of San Francisco. As part of that, he gave many of the newly made streets their names—including O’Farrell Street—and in so doing, began a long and rich naming tradition that’s probably totally invisible to those outside the craft. But for those in the know, there’s a fraternal link, wink, and nod on just about every other street corner in San Francisco.

Born to a prominent Masonic family in Ireland, O’Farrell surveyed much of Northern California on behalf of the Mexican government. After receiving land grants in the Sonoma Valley, he became a member of Temple № 14. His namesake street in San Francisco runs through the Tenderloin and ends—fittingly—at Masonic Avenue.

One of the first streets O’Farrell christened was in honor of George Washington, past master of Virginia’s Alexandria № 22. Later, four more San Francisco streets would take the names of Masonic presidents: Jackson, Polk, Buchanan, and Franklin.

Initially, Commodore John D. Sloat—the man who claimed California for the United States, and a member of St. Nicholas № 321 of New York—lent his name to what is now Sansome Street. However, around 1919, his name reappeared, this time as the main drag through the Parkside neighborhood. The Scottish Rite Masonic Center is today located at Sloat and 19th Avenue.

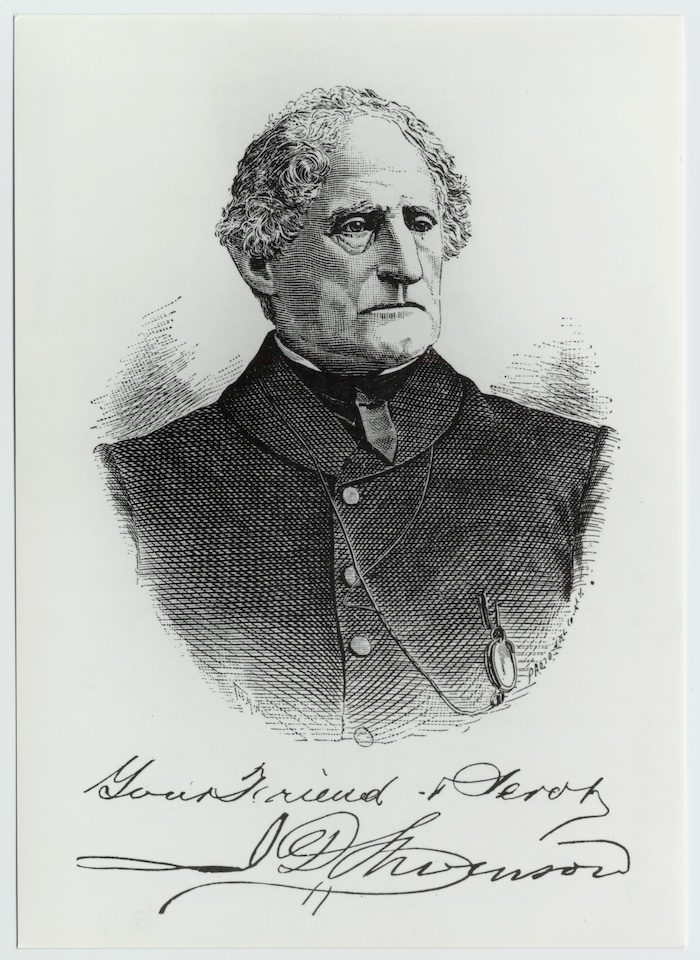

Named for Jonathan Drake Stevenson, the state’s first grand master and a charter member of California № 1 (seen above). Stevenson arrived in San Francisco as commander of a regiment of volunteers in the Mexican-American War and later made a fortune in mining and real estate.

Just south of Stevenson is a street named for Captain Joseph Libby Folsom, a member of Stevenson’s staff. After resigning from the army in 1848, he bought a huge tract of land near what’s now the town of Folsom, in the Sierra foothills, also named for him. He joined California № 1 in 1852 and was a member until his death in 1855.

San Francisco’s first millionaire and one of its most colorful early characters, Samuel Brannan led a party of 250 Mormons to California in 1845 to establish a colony. During the Gold Rush, Brannan, founder of the California Star newspaper, was the state’s ranking Mormon elder, collecting a 10 percent tithe from Mormon miners that made him rich. He and church leader Brigham Young had a falling-out, however, and Brannan eventually became a powerful figure in San Francisco politics. In 1855, the Grand Lodge prohibited all members from having “any Masonic communication whatsoever” with Brannon but, curiously, rescinded the order two years later, allowing him to join Occidental № 22.

Just south of Brannan is Townsend, named for the first licensed medical doctor in California and the first junior warden of San Jose № 10. He died in the famous cholera epidemic of 1850.

Named for Josiah Belden, an early California pioneer andthe first mayor of San Jose. Like Townsend, he was a member of San Jose № 10, joining in 1854 and serving as treasurer from 1857–59.

A curiously small strip considering its namesake, Stanford Street pays homage to Leland Stanford, former governor of California and one of the Big Four railroad tycoons. Stanford helped found Michigan City № 47 in 1855 in California’s Gold Country.

This street in the Bayview is named for Joseph Warren Revere, son of Paul Revere—hero of the American Revolution and a former grand master of Massachusetts. The younger Revere was part of the force that raised the Bear Flag at Sonoma in 1846.

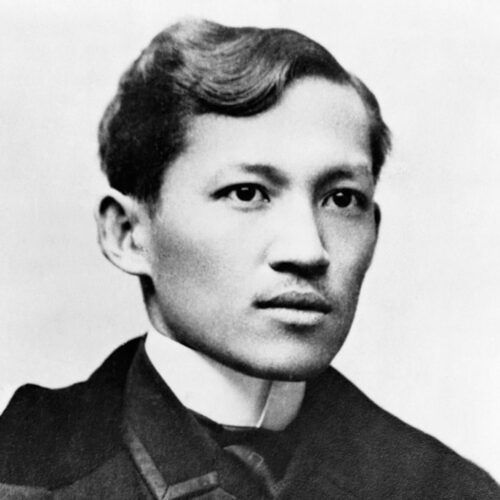

The SoMA Pilipinas Cultural District includes several streets named for Filipino national heroes, including noted Freemasons Jose Rizal y Mercado (seen at right) and Andres Bonifacio, leaders of the Philippine independence movement. Rizal Street was named in the 1990s, while three blocks of Shipley Street were renamed for Bonifacio in 1979.

Charles Gilman was nearly the first grand master of California. A past grand master of both New Hampshire and Maryland, Gilman helped organize the first Masonic convention in California and was nominated as its first leader. However, planning to return to Baltimore, he declined the honor.

Jacob Primer Leese came to San Francisco in 1836 and built one of the first houses in the Yerba Buena settlement. In 1858, he joined California № 1.

While the current spelling includes two m’s, the street was named for Lieutenant Richard Coulton Drum (with one m), an adjutant general of the Department of the Pacific during the Civil War. He was a member of Oriental № 144.

Wiliam Heath Davis, pilot of John Sutter’s vessel up the Sacramento River, was a trader in 1830s San Francisco and a member of Le Progres № 124 in Hawaii. He later helped found San Diego № 35 in 1851.

One of the longest streets in San Francisco is named for General John White Geary, a colonel in the Mexican-American War, the first postmaster of San Francisco, and, in 1850, the town’s first mayor. Geary left San Francisco in 1852 and was appointed territorial governor of Kansas, served as a major general in the Civil War, and was later elected governor of Pennsylvania. He was one of the first eight charter members of California № 1 and its first secretary.

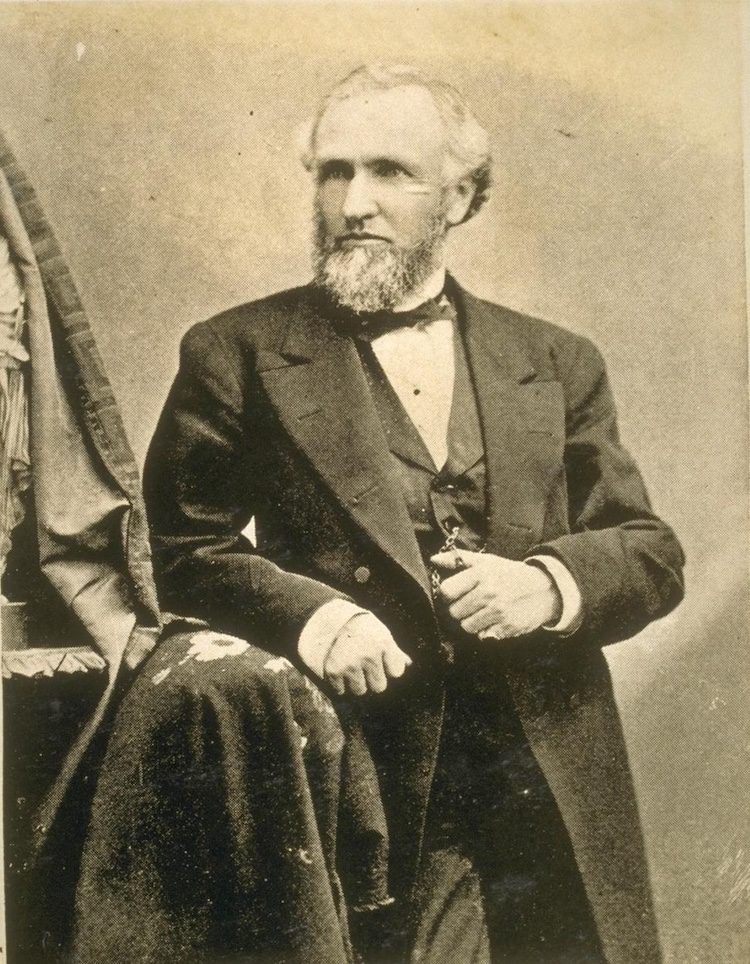

Named for James Rolph Jr., or “Sunny Jim,” the longest-serving mayor of San Francisco and one of its most popular. Rolph, a member of California № 1, resigned in 1931 to serve one term as governor of California.

Captain Charles J. Brenham was a steamboat captain who came to San Francisco in 1849, leading several trips up the Sacramento River to Gold Country. He served two terms as mayor of San Francisco and in 1855 joined California № 1.

This tiny street in North Beach is named for Thomas Fallon, who recruited a company of volunteers during the Mexican-American War in 1846 and raised the U.S. flag over San Jose. He was a member of San Jose № 10.

The outer neighborhood takes part of its name from the Crocker Holding Company, which once owned the area. Brothers Charles H. Crocker and William Henry Crocker, sons of the Southern Pacific Railroad tycoon Charles Crocker, were both extremely active members of California № 1 and deeply involved in the Scottish Rite and other Masonic organizations.

The neighborhood, which was ground zero of the hippie movement during the Summer of Love, is named for two Masons: Henry Haight, former governor of California and a member of Pacific № 136, and Munroe Ashbury, a member of the Board of Supervisors in the 1860s who helped plan Golden Gate Park. Another architect of Golden Gate Park, superintendent John McLaren, whose name graces the city’s second-largest park, near the Excelsior, was also a Mason with Pacific № 136.

Nearby, Stanyan takes its name from Charles Henry Stanyan, another city supervisor involved in the building of Golden Gate Park, who belonged to Oriental № 144.

William Beverly Cole was a surgeon, one of the founders of the University of California Medical School, and later president of the American Medical Society. In 1862, he joined Occidental № 22, remaining a member until his death in 1901.

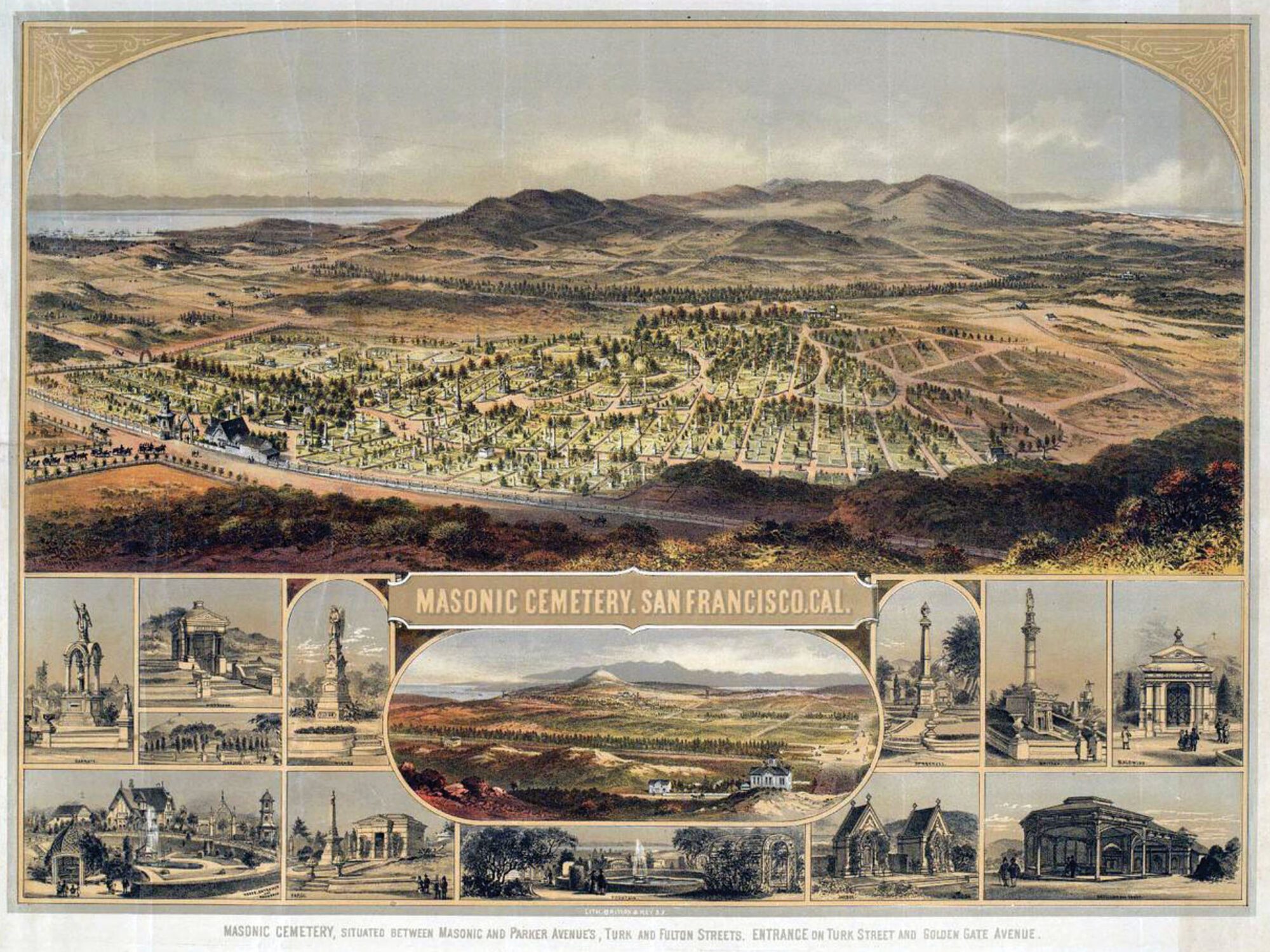

So named for the old Masonic cemetery on what’s now the University of San Francisco campus (postcard seen above). The cemetery was shuttered in the 1920s during a wide-scale reinterment of the city’s cemeteries to the town of Colma.

Ironically, Mason Street bears no connection to Masonry—like Fort Mason, it’s named for Col. Richard B. Mason, the fifth military governor of California and, to our knowledge, not a Freemason.

Photo credits:

Stevenson: Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

Rizal: Wikimedia

Rolph: Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Haight: Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Cemetery: Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

For more than a century, Fidelity No. 120 was home to a robust Jewish membership.

With his Jazz Age flair, architect Timothy Pflueger brought a signature style to San Francisco’s skyline.

San Fernando No. 343 commits to kicking off a year of public service, from school supply drives to relief efforts.