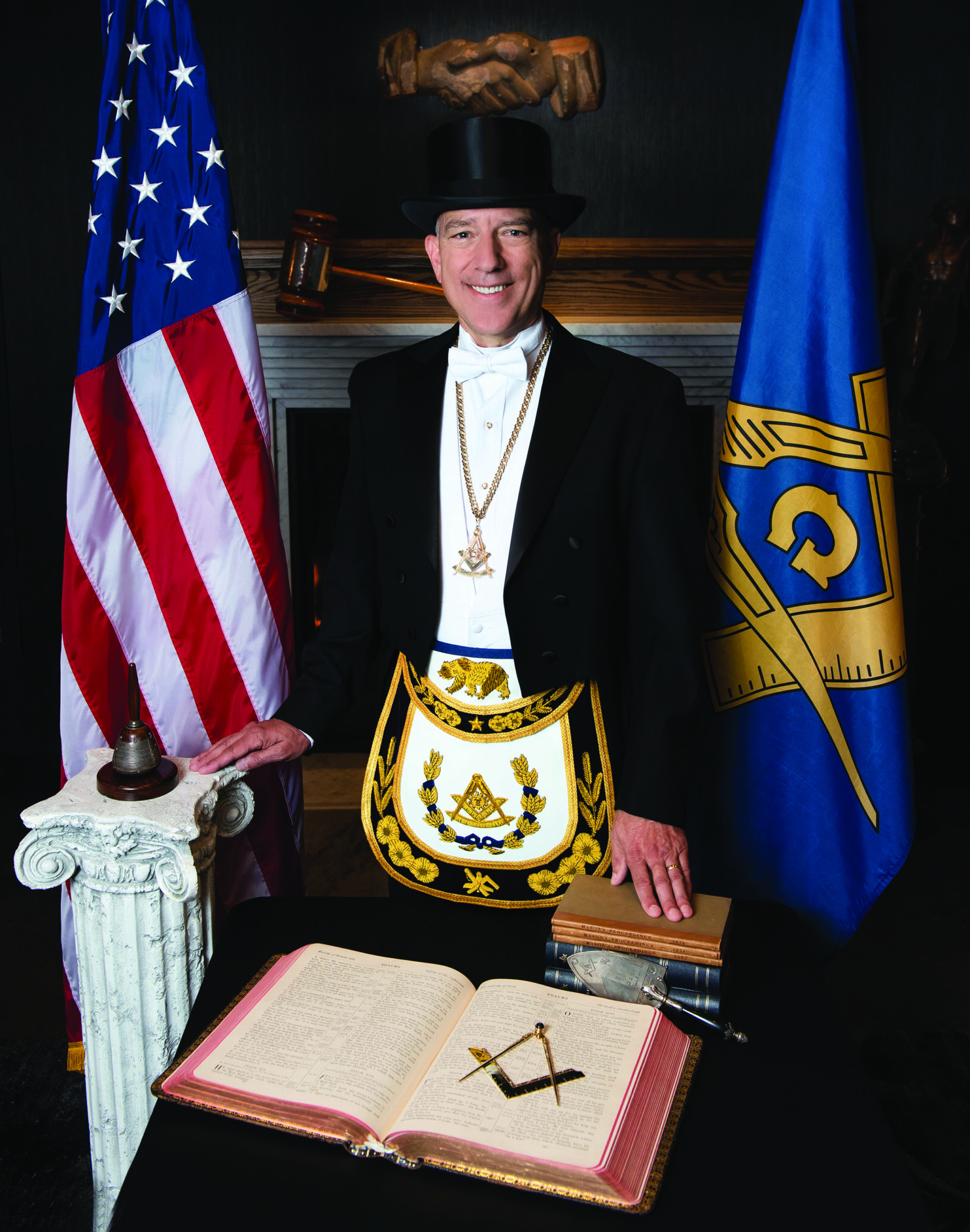

Donor Profile: Reuben Zari

How a family’s love of Masonry inspired Reuben Zari of Atwater Larchmont Tila Pass No. 614 to give back to the California Masonic Foundation.

By James Tucker, PM

Masons tend to love stuff. Our lodges are filled with it—objects of curious and sometimes unknown origin, some of which members can be very attached to, or barely notice at all. Whether it’s the ubiquitous boat on the wall (a strange custom whose basis is widely argued over) or a simple set of working tools or a portrait of George Washington in Masonic regalia, we’ve all encountered numerous examples of Masonic material culture.

I’ve always been fascinated by this stuff—particularly the sentimental and handmade. I remember in particular a silver punch bowl I once saw at the Museum of Freemasonry in London that had been brought back from a lodge in India in the 1800s. Even items of much more humble origin can contain an element of beauty and tell a story—like the hand-cut officers’ jewels I’ve seen at the historic Columbia Lodge room that were crafted from food tins during the Gold Rush.

When I first got together with a small group of Masons in 2016 to form a new lodge in downtown San Francisco—what would soon become Logos № 861—it soon became clear that we’d need a a certain number of these objects for ourselves. Unlike most new groups, though, we faced two particular considerations: First, we did not have a hall of our own. Initially, we met inside the University Club on Nob Hill, while today we’re one of seven lodges that call Freemasons’ Hall our home. That meant any lodge paraphernalia would need to be mobile enough to set up and break down before and after our meetings.

More importantly, many of our members came from backgrounds in art and design. So rather than inherit or purchase lodge adornments, we decided early that we would craft our own ceremonial objects—and that would play an important role in defining our culture.

That decision was like a flood of creative energy breaking a dam. It wasn’t just our material possessions: Wherever and however we could, our members would put their artistic signature on our lodge. Then–junior warden Benjamin Soler, a carpenter, carved the setting maul we use for the third degree. Joe Rezendes, our current master, designed and coded our website. Valdeir Faria wrote festive board ceremonies for each degree. Robert Haines, our first senior warden, created our second-degree floor cloth. As a professional printmaker and designer, I worked on our banner, aprons, and tracing boards. Then there’s the pièce de résistance: Freemasons’ Hall was designed by architect Kevin Hackett, our lodge brother.

To anchor us in this culture, we made a pact that this creativity would live on in the lodge as candidates progressed through the degrees. Today, members present “workpieces” when they’re ready for their next degree. These tend to be more artwork than homework. Pat Clos, a musician, wrote and performed songs for each of his degrees. Kevin Jones, a videographer, made his presentations as—you guessed it—videos. Most recently, Adam Dexter created an immersive audio experience for his entered apprentice workpiece.

This culture of making has defined Logos № 861, and I hope it will continue to do so for years to come. Rather than simply adding to a growing collection of stuff, I see this as a way to impart the teachings of Masonry to future members. By creating our own Masonic objects and traditions, we not only tap into our creative potential but also contribute to the ongoing narrative of Masonry.

James Tucker is an artist, designer, and past master of Logos № 861.

James Tucker explains the significance of some of the lodge’s most memorable bits of material culture.

“For Adam Dexter’s Entered Apprentice degree workpiece, he designed a sound installation. It was super cool; we all wore headphones and blindfolds and listened to this sensory piece he created that felt like he was sitting right next to us. It explored the trust element of the first degree. It was creepy— in a good way.”

“This is our charter-member lodge jewel, which I designed. Those are Greek letters spelling LOGOS inside the star. The circle represents the universe or cosmos; the triangle is divinity, or creation; and the star represents humankind within it. This was sort of a proto-symbol for our lodge—our new symbol, on the banner, is a lot simpler. But it’s fun to see its evolution over time.”

“The double-sided apron is really fun. It started out as a watercolor I did, and now they’re digitally printed onto the leather apron by Brother Patrick Craddock at the Craftsman’s Apron. The memento mori on the inner side is never really shown; you’re bringing that toward yourself as a personal reminder. The front is our call to arms: ‘Green adorns the earth and never dallies, nor does it wait to plot or conspire. Forever it’s on the move.’”

“Rather than a Bible, we use a Volume of Sacred Law for our stated meetings. It contains excerpts from every major religion. It’s more inclusive, since we have members from different faiths. Plus, Masonry is a universal thing, right? I wanted for us to make this ourselves, but then I found one made by Columbia University’s Theological department in the 1940s. It was probably better than whatever we could make!”

How a family’s love of Masonry inspired Reuben Zari of Atwater Larchmont Tila Pass No. 614 to give back to the California Masonic Foundation.

Grand Master Sean Metroka explains why building new lodges is the key to the future of the fraternity.

The archived papers of California’s Masonic leaders yield important historical insight into the growth and development of the fraternity.