Freemasonry’s Spiritual Cousins

The California Masonic Symposium returns to explore Masonry’s spiritual roots.

A man is walking through a mostly deserted cemetery when he comes upon a memorial service in progress. The gathering seems different somehow. Curious, he stops to listen. Dozens of men of all ages are lined up in pairs, side by side. They march toward the casket, all dressed in dark suits and wearing simple white aprons. Upon the casket lies another apron.

The speaker’s eulogy is full of arcane terms and esoteric references. At last, he holds up a sprig of acacia, and on behalf of those present, offers the deceased a final valediction. “Thy spirit shall spring into newness of life and expand in immortal beauty, in realms beyond the skies,” he recites. “Until then, dear brother, until then, farewell!”

This is a Masonic funeral service. Apart from the cornerstone-laying ceremony, a Masonic funeral is one of the most visible public displays of Freemasonry there is.

In 2020, members performed a Masonic funeral service for the civil rights leader and congressman John Lewis at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Two centuries prior, George Washington received a Masonic send-off at his public memorial.

The Masonic funeral ceremony is one of the most conspicuous examples of Masonic values materialized into action. It’s also very often the prism through which outsiders first encounter the craft—a rare glimpse into the lodge life of the deceased that many know little about. That’s fitting, because the concepts of death, rebirth, and legacy are important elements to the teachings of Freemasonry.

Today, these tend to be abstract ideas, jumping-off points for discussion of esoteric concepts. But historically, managing death has been one of the most important functions of the fraternity. Making sure that a departed brother received a proper burial and remembrance was traditionally one of the most important benefits of Freemasonry. Even now, the fraternity plays an important role in times of death. Masons are known to travel from miles around to attend the funeral services of their fellow members, even those belonging to other lodges.

Glenn Gordon Whiteside is one such member. Whiteside grew up in a Masonic family and began as a member of the Order of DeMolay. He estimates that he has attended at least 70 Masonic funerals. Whether or not he knew the deceased personally, Whiteside says, he considers it his duty to stand in as a representative of the fraternity, just as generations of Masons have done before. “It’s your job to let the family know that Masonry was a part of his life, that he was respected, and to show that he was our brother,” Whiteside, of Pacific-Starr King № 136 in San Francisco, says.

John Bermudez is another such member. He is general manager of Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma and a member of California № 1. “What I find most impressive about Masonic funerals is that they show that we value our members’ lives,” he says. Often in his job, he’s witnessed services where hardly any family members attend. “But with Masonry, you have all these brothers who show up to honor him. It shows that this was a person who lived and meant something. I appreciate that, and I’m sure our brothers who are no longer here appreciate it, too.”

Members often refer to Freemasonry as a system of morality, one intended to help guide them toward a more fulfilled life. But the context of those life lessons is often mortality. From the ritual death and rebirth that members undergo to the symbolism of the eternal soul, Masonry attempts to provide its members with “inspired vision to enable us to look with faith beyond the veil,” as is said during the funeral rite.

Perhaps the most common of these symbols is the concept of memento mori—the reminder of one’s inevitable demise—represented by the skull and crossbones. (The symbol, while not specific to Freemasonry, appears in certain Masonic contexts. Chief among them is the Knights Templar, a Christian offshoot of the fraternity.)

Though the skull has come to represent all things spooky in popular culture, for centuries memento mori has been used in art and literature as an uplifting device. That’s most evident in the 17th-century art form of the vanitas. These were still-life paintings depicting the pleasures of life juxtaposed with symbols of death or ephemerality, like bubbles or wilting flowers. By reminding us that our lifetime is short, memento mori invokes another Latin phrase—carpe diem, an admonition to live your fullest life here and now.

The skull isn’t the only visual representation of memento mori. Within Masonry, they are legion. The hourglass—sometimes shown with wings—is a reminder of the unceasing march of time. According to Albert Mackey’s Masonic encyclopedia, the hourglass “reminds us by the quick passage of its sands of the transitory nature of human life.” Similar to that is the sprig of acacia, an evergreen leaf referenced during the Masonic funeral ceremony. The acacia is described as “an emblem of our faith in the immortality of the soul” and symbolizes “perpetual renovation.”

Other Masonic symbols echo that theme: Father Time, or Saturn, is seen in Masonic contexts as a reminder that “time, patience, and perseverance will enable him to accomplish the great object of a Freemason’s labor.” That phrase is echoed in the Masonic funeral service, when the deceased is finally called from his labor. Finally, the ruler, or 24-inch gauge, symbolizes the 24 hours of the day. During the funeral ritual, the master invokes the ruler while stating, “During the brief space allotted to us here, we may wisely and usefully employ our time, and, in the mutual exchange of kind and friendly acts, promote the welfare and happiness of each other.”

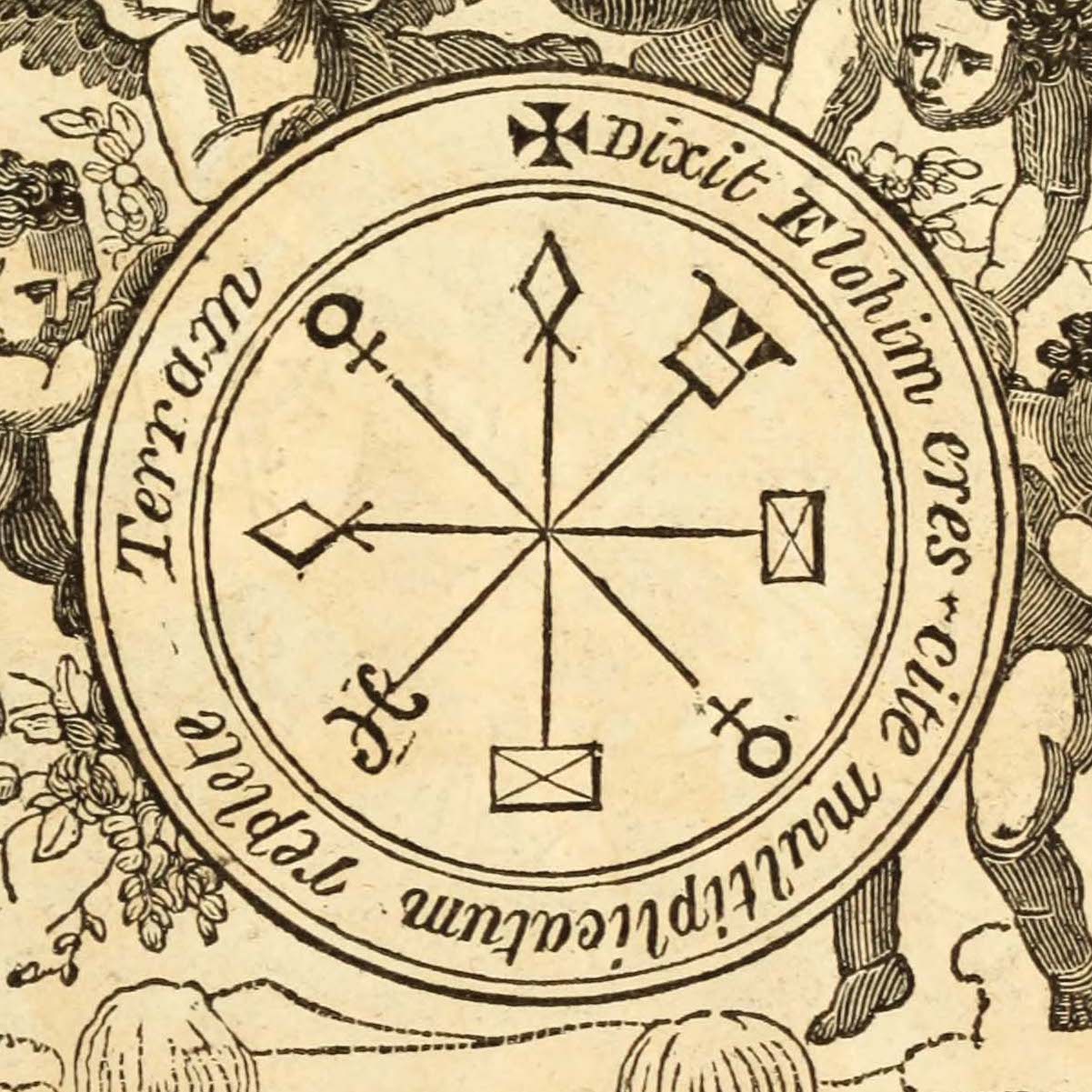

Above:

An English 1825 tracing board by John Harris depicting the Master Mason degree. Courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

Any discussion of death and the afterlife inevitably leads to an ontological reckoning. To say that one believes in life after death or in the existence of the soul is an inherently spiritual statement, an expression of faith. Even distinguishing material and spirit, for some, raises uneasy metaphysical questions. It’s not surprising that for most Americans, death can be an uncomfortable topic.

Masonry, in dealing with such questions, treads a fine line. Luis Martinez, a member of Golden Gate Speranza № 30, is an expert in comparative religion. “Freemasonry is not a religion. However, it is religious,” he explains. While Masons point out the universality of Masonry, which has always been open to candidates of all faiths, most jurisdictions (including California) specifically require candidates to express a belief in God—or at least in a higher power.

Despite Masonry’s many lessons on life and death, Martinez points out that it isn’t dogmatic about mortality and the afterlife. He, for one, is comfortable with leaving room for mystery. “If you think you know all the answers, then why bother exploring?”

That’s a sentiment shared by others in the fraternity. “If you were to ask 10 Masons about life after death, you would get 10 different opinions,” says Kyle Burch of Friendship Lodge № 210 in San Jose.

Burch is the spiritual director of the Spiritual Growth Institute and an expert on Rosicrucianism and other esoteric traditions. Masonry may demand faith from its members, he says, but the details of that faith are left to the individual.

That kind of personal interpretation extends to questions of the afterlife. To some, winged cherubs playing harps might be an image of heaven. To others, reincarnation and the continuation of the cosmic life cycle is their reality. To still others, death is final, an eternal sleep. But even that view can be imbued with meaning: It may represent the soul’s reunification with its source, absorbed like a drop of water returning to the ocean.

Freemasonry can offer members a context for approaching questions of death and the afterlife often left unexplored within secular society. But those lessons are not necessarily unique to the craft. Many cultures and faiths involve stories of rebirth or resurrection. This theme was especially captivating to the adherents of the ancient mystery schools that provide a philosophical backdrop to Freemasonry. Among them are the Eleusinians, whose initiates performed a mock death and rebirth ritual in which a man was born again. “The death-before-death ritual is relatively universal across cultures and religious belief systems,” Burch says. “I think this speaks to the universal truth of this concept.”

Mackey, too, acknowledges the common themes between the Eleusinian Mysteries and Freemasonry. Both systems used allegory and a morality play to convey their message. He interprets that message as “the restoration from death to eternal life.” That restoration culminates when “the initiate ceased to be a mystes, or blind man, and was thenceforth called an epopt, a word signifying he who beholds.”

In facing one’s death, even if only as an act, the hope is that one will confront the fear of mortality and live with courage and intention.

“Our brother has reached the end of his earthly toils,” state the words of the California Masonic funeral ritual. It continues, “the brittle thread which bound him to earth has been severed and the liberated spirit has winged its flight to the unknown world. The silver cord is loosed … the spirit has returned to God who gave it.”

These words echo Ecclesiastes 12:6. There are layers of meaning in the symbols of the thread and the cord, both of which carry significance in Freemasonry. Heaven, in the Masonic service, is described as the “celestial lodge above.” George Whitmore is perhaps the Mason in this state who’s best-acquainted with that particular lodge. A past assistant grand lecturer, Whitmore, of Victorville № 634, is tasked with certifying Masons to lead Masonic funerals. As such, he’s performed the ritual at plenty of them. In each instance, he says, he’s reminded of the solemnity of the occasion and makes a point of ensuring each service is performed word-perfect. “He’s my brother,” Whitmore says of the deceased. “I want to afford him every dignity and honor.”

Masonic concepts of the soul, immortality, and reincarnation may seem heady for most. But as technology increasingly forces more philosophical reckoning with questions of humanism, there’s still room for a spiritual framework for approaching our mortal end. And for the lessons it holds for our time on earth.

Even Einstein understood that. Michelle Thaller, a physicist with NASA, summarized his theory this way: “Time is a landscape. If you had the right perspective on the universe, you would see all of it laid out in front of you. All past, present, and future as a whole thing.”

What Masons are left with, then, is the notion of what might be called the infinite present. The writer Joseph Campbell may have captured that sentiment best. “Eternity is that dimension of here and now that all thinking in temporal terms cuts off,” he wrote. “The experience of eternity right here and now, in all things, whether thought of as good or as evil, is the function of life.”

“It’s said that our character is set by the time we are 8 years old. The same is true of how we handle money. When we are intentional with what we do with our financial resource—both while living and after we are gone—we are sharing our values with those we love.”

—PGM Russ Charvonia, financial advisor, Channel Islands № 214

_______________

“Several years ago in our lodge, a very young father of four passed away unexpectedly, throwing his family into chaos. The outpouring of support from Masons was on an epic level, from all corners of the planet. However, one of the unexpected legacies was that it caused other families to think about their own situations and answer questions like, ‘How would my family pay for this?’ or ‘Who would take care of us?’”

—Wil Smith, Chairman of Grand Lodge Investment Committee and Past Master, Irvine Valley № 671

_______________

“Tomorrow is promised to no one. The planning you do today will alleviate a great headache for someone down the road. So leave a trail of breadcrumbs for your loved one—the name of your key advisors, contacts, website logins and passwords— and some basic thoughts on the the how and why of you set things up the way you did.”

—Eric Hatfield, Grand Pursuivant, Santa Monica-Palisades № 307

_______________

“By creating a charitable remainder trust and funding it with highly appreciated assets like stocks, you neither incur capital gains nor pay taxes on the growth or income. Not only can this provide a lifetime income for you and your spouse, but you can leave a charitable gift that, like the acacia, will be your enduring legacy.”

—Alex Teodoro, Trustee of CMF and CMMT Past Master, Pacific-Starr King № 136

_______________

“This is simple stuff, but it’s important: Make sure your passwords are easy to find among your estate-planning papers, particularly for your bank or brokerage accounts. If you have a safety deposit box, make sure your heirs are named as co-signers and that the combination to any safe you own is similarly memorialized.”

—David Studley, attorney, Past Master, Calaveras Keystone № 78

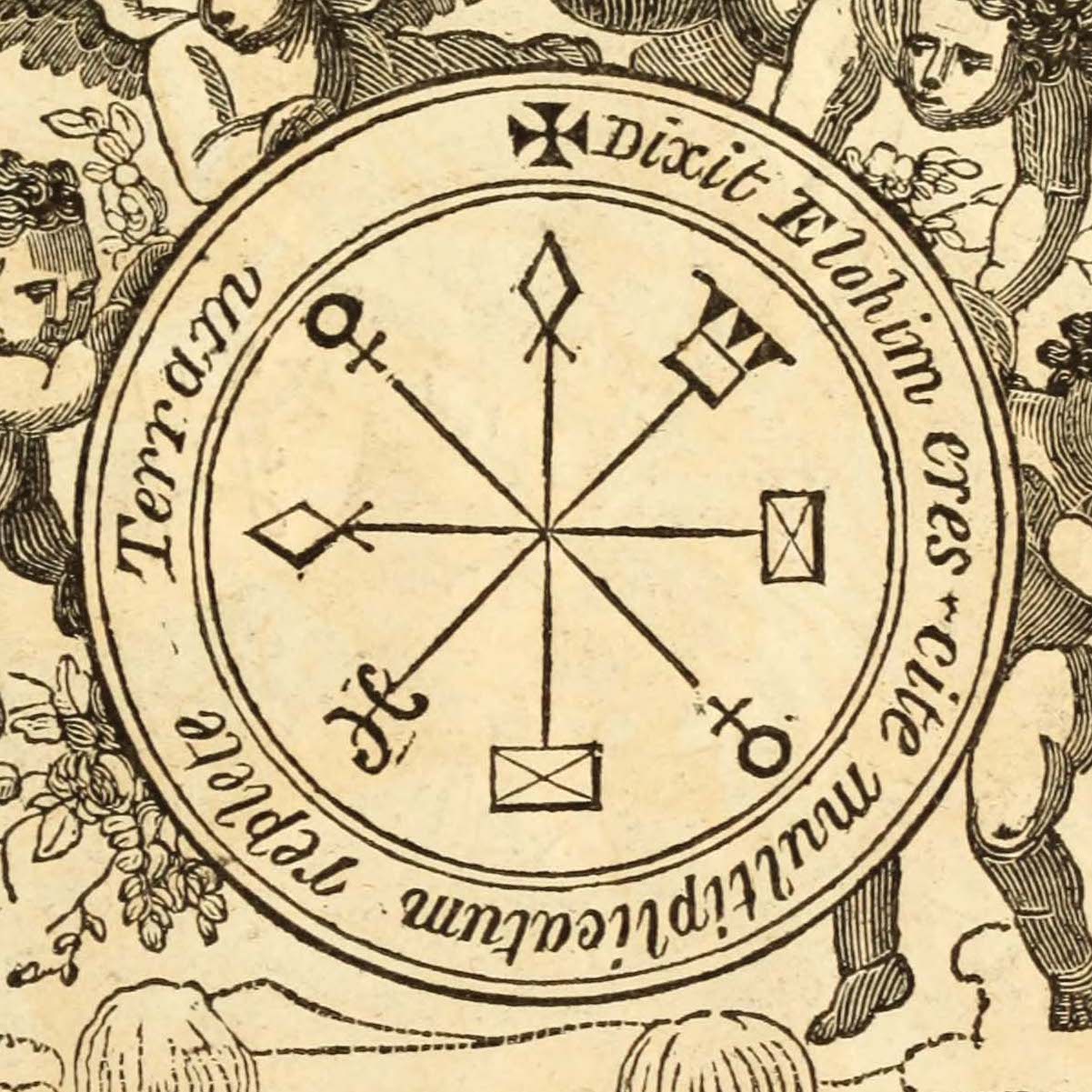

Above:

Masonic Mourning Piece for Rev. Ambrose Todd, 1809 by Eunice Pinney, Windsor, Connecticut. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum.

TOP ILLUSTRATION BY

Anthony Freda

The California Masonic Symposium returns to explore Masonry’s spiritual roots.

An aviation expert, this SoCal Mason has seen Masonic relief up close. That’s why now, he makes a point of giving back.

Masons4Mitts returns for another season with the support of the Masons of California and the California Masonic Foundation.