More than Retirement Homes: The Wide World of Masonic Relief

The Masonic Homes of California are more than just retirement communities. Take a tour around the wide world of Masonic assistance.

By Laura Benys

When the Grand Lodge of California purchased the land in 1893 that would become the Masonic Homes of California, it paid $32,500 for the 268 acres of rolling hills and pastureland situated in the Alameda County town of Decoto, about midway between Oakland and San Jose. By 1898, when the first Masonic Home for Widows and Orphans was formally dedicated, the total budget for the project, including construction and other fees, came to about $140,000. That’s about $5 million in today’s dollars.

As the Masonic historian Thomas W. Storer noted almost a century later, it was the bargain of a lifetime.

Now, on its 125th anniversary, the Masonic Homes is celebrating a different kind of return on investment. The organization has evolved far beyond the imaginations of its earliest leaders, reaching more people with more services and in more ways than ever. Far from its humble origins as a haven for widows, orphans, and elderly members of the fraternity, the Masonic Homes’ remit today has broadened to include mental wellness, social support, financial assistance, and case management for people of all ages, no matter their location.

It has also distinguished itself as a leader in the growing fields of memory care and skilled nursing, become a valuable partner to schools and civic organizations, and adapted to a largely virtual-first environment. It has, in short, proved its value many times over. To the organization’s leaders—not to mention the fraternity that supports it and the tens of thousands of people it has served—the Masonic Homes of California’s worth is simply immeasurable. Says Gary Charland, its outgoing CEO and president, looking out over the grounds that his fraternal forebearers so wisely invested in those many years ago, “It’s priceless.”

To look up at the imposing brick façade of the original 1898 administrative building at the Masonic Homes is to appreciate its permanence and durability. And yet the reality is that change has been a hallmark of the organization since the very start.

When the doors were first opened to the building in 1899, it was to a modest cohort: five widows, 16 Masons, and 25 children made up the inaugural group of residents. It didn’t stay small for long. Within a decade, the fraternity began searching for a second campus, dedicated to children. And in 1906, it did just that, moving its youngest residents to a former hotel in the town of San Gabriel. (Within a few years, they were moved again to a compound built on a retired citrus farm in Covina.) The decision still amazes Joseph Pritchard.

“Building the first Masonic Home had been a massive effort,” says Pritchard, the organization’s current chief operating officer. “The fact that a decade later, the fraternity said, ‘We need to do even more,’ that’s incredible.”

Looking back, the Masonic Homes came around just in time. In their first century, the two campuses helped the fraternity weather two World Wars and the Great Depression. They helped it manage the growing ranks of elderly and indigent Masons and their widows, and gave hundreds of young people a caring upbringing at a time when orphans were often sent to institutions that offered anything but. The Masonic Homes’ scrapbooks tell of childrens’ farm antics and movie nights in Covina, and of elderly people aging with dignity in the East Bay. (The town of Decoto was incorporated into what is now Union City in 1959.)

But times were, as ever, changing. As the fraternity’s huge wave of members from the Greatest Generation reached their senior years, the demographics of those needing help—and what help they needed— began shifting.

So the Masonic Homes evolved. Both campuses were upgraded and expanded several times over, including the construction of an on-campus hospital in Union City in the 1960s and the admittance shortly after of non-ambulatory residents. In Covina, a transformation in the 1970s turned the children’s home from a dormitory into a series of family-style cottages designed by the influential midcentury architect A. Quincy Jones. By 1986, with the number of orphans declining and the wait list for seniors growing, that campus was converted yet again to accommodate the elderly, by then living side by side with the young. In the 1990s, as part of an overall campus master plan, the Masonic Homes in Union City updated, remodeled, or retrofitted nearly all of its original buildings. That included a major renovation to the Wollenberg building to accommodate more assisted-living apartments.

“As you see the Masonic Homes grow over the first 100 years, you see the expansion to meet the fraternity’s needs,” Pritchard says. “You see, ‘We need to add this building to house the children better. We need to expand our farm to produce more food. We need to build Wollenberg to properly house the sick.’ That all happened pretty swiftly.”

The pace of change hasn’t let up in the 21st century. The children’s program, whose model had adapted over the years in conjunction with new thinking about youth and foster care, was reborn in 2011 as the Masonic Center for Youth and Families, an innovative organization offering educational assessments, therapy, and mental wellness for children, adults, and families. The non-resident assistance program, originally a fund used to support seniors who were ineligible for entry into the Masonic Homes, was transformed into Masonic Outreach Services, a sprawling program that connects Masons in need and their family with housing, finances, and benefits in their own communities.

Sure, the seniors at the Masonic Homes in Union City sometimes jokingly refer to themselves as dinosaurs. But in terms of geologic time, they’re practically tadpoles, at least compared with the campus’s previous inhabitants.

That was brought into dramatic relief one day in 1971. In preparation for a planned redevelopment, construction workers dug test trenches throughout the campus to study foundation conditions. The longest of the trenches was 1,290 feet.

That’s where, at a depth of 16.5 feet, workers discovered the skull and tusks of a prehistoric mammoth. After identifying the remains, archaeologists from the California Academy of Sciences were called in to lead the exhumation of the fossils. The remains were taken to the Grand Lodge of California’s archive for safekeeping until they could be donated to a museum.

The Columbian mammoth was, for a period during the late Pleistocene period (beginning 2.6 million years ago and ending 11,700 years ago) perhaps the mightiest of the megafauna that roamed the San Francisco Bay Area. Standing 13 feet tall and weighing up to 24,000 pounds, it was twice the size of a modern African elephant.

The fossil discovery at the Masonic Homes may have been significant, but it was not unheard of for the area. In fact, during the 1940s, a group of “boy paleontologists” gained national attention on television, on the radio, and in Life magazine for excavating more than 29,000 fossils from the Bell Sand and Gravel Quarry, about eight miles south of the Masonic Homes at the base of the Irvington Hills in what is now Fremont. Among their discoveries were mammoths, saber cats, horses, camels, a dire wolf, and a never-before-seen species of antelope with four antlers, called Tetrameryx irvingtonensis.

According to the Washington Township Museum of Local History, the finds were so important that Irvington was given its own marker in geologic time. That didn’t stop the inexorable march of progress from trampling over it, though: In 1970, the quarry site was sold to the state and leveled for the construction of today’s interstate 680–route 238 interchange. Meaning that whatever other fossils might have been contained there have been permanently paved over—at least for the next millennium or two.

Above:

The sun rises above the hills behind the Masonic Homes of California’s Union City campus, first opened in 1898.

Under Charland, who became executive vice president and CEO in 2013, the Masonic Homes continued to develop new programs and services. It designed and launched an influential and first-of-its-kind memory care program called Stepping Stones for those dealing with dementia and other memory loss conditions—one of the fastest-growing needs in senior care today. Stepping Stones was proactive, progressive, and flexible enough to move around campus, making the most of the unique space.

On both campuses, the Masonic Homes began embracing technology in a way that remains head and shoulders above what most continuing-care retirement communities can offer, from installing voice-automated apartment commands to smart toilets and robot caddies. It joined the Thrive Alliance, a national group dedicated to discoveries in aging care, and became a headliner at the LeadingAge California conference, where its leaders regularly present their approach to using technology to battle staffing shortages and improve residents’ quality of life.

The fraternity also embarked on another experiment: opening select services to the wider public.

Although the Masonic Homes’ mission has always been to provide relief to members of the fraternity and their families, it has also experimented with ways to bring the best of its services to the world beyond its doors. The children’s program was the first to do so, dropping the requirement of Masonic affiliation for entrants in 1997. In 2010, in response to the recession and a growing community need, the Acacia Creek Retirement Community opened to both Masons and non-Masonic applicants. In both cases, the results were unqualified successes.

“One of our concerns was the fear of ‘them’ and ‘us,’ creating two different hierarchies,” says Past Grand Master Ken Nagel, who presided over the opening of Acacia Creek. “That could not have been farther from what actually happened. They’ve blended together, and it’s a fantastic relationship.”

Continuing that trend, the Masonic Homes opened Transitions in 2015, a short-term rehabilitation center on its Union City campus that serves patients as they recover from a stroke, surgery, or major illness. Today, the clinic is ranked among the nation’s best. When the Masonic Homes board of trustees began mapping out its latest five-year campus master plan, their vision included, for the first time, long-term skilled nursing and memory care for the general public.

Meanwhile, off campus, another crucial transformation was taking place. By the 2000s, it had become clear that two residential campuses could not hold the fraternity’s rapidly aging population. The answer was for it to expand outward.

Masonic Outreach Services was one way to do that. In addition to providing financial assistance to Masons who’d chosen to age in place, it began offering advice, referrals, and case management to people throughout the state. “You enabled us to keep our dignity and self-respect,” wrote one client, thanking his care manager for helping him and his wife remain in their home.

By 2009, in the wake of the housing crisis, the organization opened similar supports to Masons under 60. One such recipient, who’d been out of work and relied on emergency funds to rebuild his life, put it plainly: “Masonic Outreach saved my life.”

Another approach to bringing support directly to members has come through the Masonic Center for Youth and Families. That transition began in the early 2000s, as the number of children being placed in group homes fell drastically. Instead, greater emphasis was placed on therapy and providing supports for struggling parents. That led to the opening of the Masonic Family Resource Center, a one-stop-shop for families in need, which provided short-term housing for children as they and their parents worked toward reunification. That, in turn, led to the opening in 2011 of MCYAF, which follows a community health model, designed to help as many children and families as possible, wherever and however they need it most.

“Rather than hanging up a shingle that says, ‘This is what we do,’ you start by looking at the surrounding community and assessing its needs,” explains Kimberly Rich, MCYAF’s executive director. “Then you design programs to meet those needs.”

That’s a good way to explain the Masonic Homes philosophy: rise to the community’s toughest challenges, whatever and wherever they may be. For all the change that’s characterized the organization for 125 years, that part has remained the same.

The late Jack Wright flew with the Blue Angels. Dick Sullivan piloted a B-52 in the Air Force. Both, however, admitted that in many ways, flying their model aircraft at the Masonic Homes’ on-campus airfield was even more difficult. “When you’re landing, the model plane comes straight at you—it’s not like sitting in an aircraft,” the late Jack McClellan said in 2018.

All three men were part of the Masonic Homes’ Flying Club, a group of approximately a dozen members of the Masonic Homes and Acacia Creek who in 2004 transformed a barren stretch of hillside behind the Union City campus into a 100-foot-long asphalt runway. Members typically fly their own craft, but the club has two model planes it loans to novices, as well as a flight simulator.

“I got a real sense of accomplishment,” McClellan said. ”It’s not easy to take off and land perfectly every time. The first time I flew, it was kind of scary—I even had shaky knees. But I kept trying. It’s really fun.”

If the simple lines, walls of glass, and low-slung design of the Masonic Homes in Covina seem quintessentially California modern, well, that’s because they are.

Designed by Archibald Quincy Jones, the former dean of the architecture department at USC (and designer of Walter Annenberg’s Sunnylands estate in Rancho Mirage), Quincy was hired by the Masonic Homes Board of Trustees in 1968 to execute the campus master redevelopment plan. Between 1968 and 1973, that included the construction of eight new single-family-style cottages; a community building that included a cafeteria, library, and offices; and new roadways and landscaping.

While the Masonic Homes are not typically listed among Jones’s most iconic designs, they feature many of his work’s most distinctive characteristics, from the high ceilings, angled rooflines, and post-and-beam construction to the emphasis on connective greenbelts. In that regard, his legacy is a lasting one. Though Jones was largely overshadowed by his more famous midcentury contemporaries (and frequent collaborators) Joseph Eichler and Richard Neutra, he nevertheless did much to raise the design of humble buildings in California “from the simple stucco box to a structure of beauty and logic,” noted architect Cory Buckner.

Above: The Masonic Homes of California’s Covina campus opened in the early 20th century and was expanded in the 1960s and ’70s.

In the U.S. and beyond, health care is in a moment of crisis. Health providers face critical staffing shortages. Patients and families face soaring costs. The population’s average age continues to rise, and with it, so does the need for high-level care for seniors. Housing, meanwhile, has become highly unaffordable, particularly in California. Young people don’t have it much easier, amid a mounting youth mental health crisis that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

In the face of all that, the Masonic Homes is doing what it has always done: Recognize challenges. Adapt to meet them. And point the way forward. “What distinguishes us from every other organization out there?” Charland asks. “We make a commitment to take care of each other. Those aren’t just empty words. Through the Masonic Homes, we do it.”

The fraternity continues to invest in that commitment. In Union City and Covina, the Masonic Homes recently completed a $140 million campus master plan, fueled by the most successful fundraising campaign in California Masonic history. Both campuses, which house a combined 400 residents, are now regarded as gold-standard experts in senior care, memory care, and compassionate assisted living. They raised overall capacity by 58 percent, increased the share of space devoted to the growing need for assisted-living, skilled nursing, and memory care, and optimized every inch of their facilities. In Union City, that included updating outdoor spaces, transforming existing buildings into assisted-living communities, and adding flexible, best-practice housing models for those in need of even more elevated care.

But the biggest change has been the opening of two new facilities that demonstrate the organization’s new direction. In Union City, the Pavilion at the Masonic Homes opened in 2021, offering 28 brand-new apartments for residents requiring high-level assisted living or who are dealing with memory loss. And in Covina, the just-completed health center features 32 apartments devoted to memory care, long-and short-term care, and skilled nursing.

In both cases, the result is that residents know they can always find the support that they or their partner need without ever having to move away. And in keeping with the organization’s vision of bringing more services to more people, they’re both open to the general public.

“I have to say, nothing in the state can even remotely compare,” says Charland of the two new facilities. “It was never just about building a building. It was about creating a lasting landmark.”

Away from campus, the Masonic Homes has been creating a different kind of legacy. Out in the cities, towns, and rural stretches of the state—and beyond—Masonic Outreach Services has grown into a powerful vehicle for bringing services and relief to those who need it most. It’s not just Masons, either: The Masonic Assistance help line offers free information about community resources to anyone who calls, Masonic or not. Through novel and strategic partnerships, MCYAF is now embedded in several schools and districts, as well as on the Masonic Homes campuses, offering everything from therapy for children and families to telehealth for lonely seniors.

“The Masonic Homes is not about just senior care,” says Larry Adamson, a past grand master and current chairman of the Masonic Homes board of trustees. “It’s about care, period.”

In 1998, on the centennial of the Masonic Homes of California’s opening, past grand master and then-president Stanley M. Cazneaux summed things up nicely: “The Masonic Homes of California exemplify all that is best in Freemasonry.”

A quarter-century later, that statement remains as true as ever. On behalf of the generations of Masons who have taken the obligation to provide relief to their “distressed worthy brothers,” the Masonic Homes is taking that promise to new levels.

And it’s needed now more than ever. The number of seniors in California is nearly 30 percent of the overall population and rising. Memory loss has overtaken running out of money as the top concern for the elderly. Meanwhile, rates of depression, suicide, and social isolation in youth have skyrocketed. Wildfires, floods, and other catastrophic storms are wiping out entire communities with increasing frequency. More challenges will surely emerge in the years to come. The Masonic Homes will continue to adapt. It will have to.

“We have more to go,” Adamson says. “But our brothers have been so charitable in paying it forward that we have the ability to do things other organizations can’t even consider. We can make this world a better place for everybody. That’s what I think our teachings tell us we’re supposed to do.”

It’s a mission that resonates with Charland, who in July stepped down after a decade at the helm. Even from outside the organization, he’s still amazed by the timelessness of it.

“Think about how central that commitment is to Masonry,” he says. “It means you don’t have to go it alone in the world.”

First it was a monument to a death in of one of California’s prominent families. Then, for years, a testament to the state’s Masonic fraternity. Today the marble statue of a bowed angel that’s visible from Mission Boulevard in Hayward is a universal symbol of grief and empathy, relatable to anyone dealing with sorrow or loss. The statue, which marks the Masonic plot within the Chapel of the Chimes Cemetery, has certainly seen a lot of history. It was first commissioned by Jane Stanford, who along with her husband, Leland, founded Stanford University.

The statue was meant to commemorate her brother Henry, who died in 1901. Made by the Italian artist Antonio Bernieri, the artwork was a replica of one made by William Wetmore Story, called The Angel of Grief Weeping Over the Dismantled Altar of Life.

For five years, I lived in the Stanford arboretum. However, the 1906 earthquake damaged the seven-ton Carrara marble edifice. In 1908, another of Stanford’s brothers, Charles Lathrop, arranged to have a replacement made. That one remains at Stanford to this day.

What happened to the original remains a mystery. But in 1920, the Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of California noted that “Through the generosity of Brother Max Hornlein, the beautiful statue of ‘Grief,’ formerly resting in the grounds of Stanford University, now occupies the center of the Home cemetery.” That cemetery has since been incorporated into Chapel of the Chimes.

It’s not known how Hornlein came to own the statue. A successful turn-of-the-century businessman, Hornlein was a member of Sacramento No. 40, as was his brother, Hugo. Both were also members of the Knights of Pythias. Max Hornlein died in 1926, though his gift to the fraternity lives on for future generations to observe and contemplate.

PHOTOGRAPHY/ILLUSTRATIONS COURTESY OF:

Valerie Chiang

Winni Wintermeyer

Peter Prato

The Masonic Homes of California are more than just retirement communities. Take a tour around the wide world of Masonic assistance.

Thanks to a novel partnership with Dig Deep Farms, the agricultural heritage of the Masonic Homes is being brought back to life.

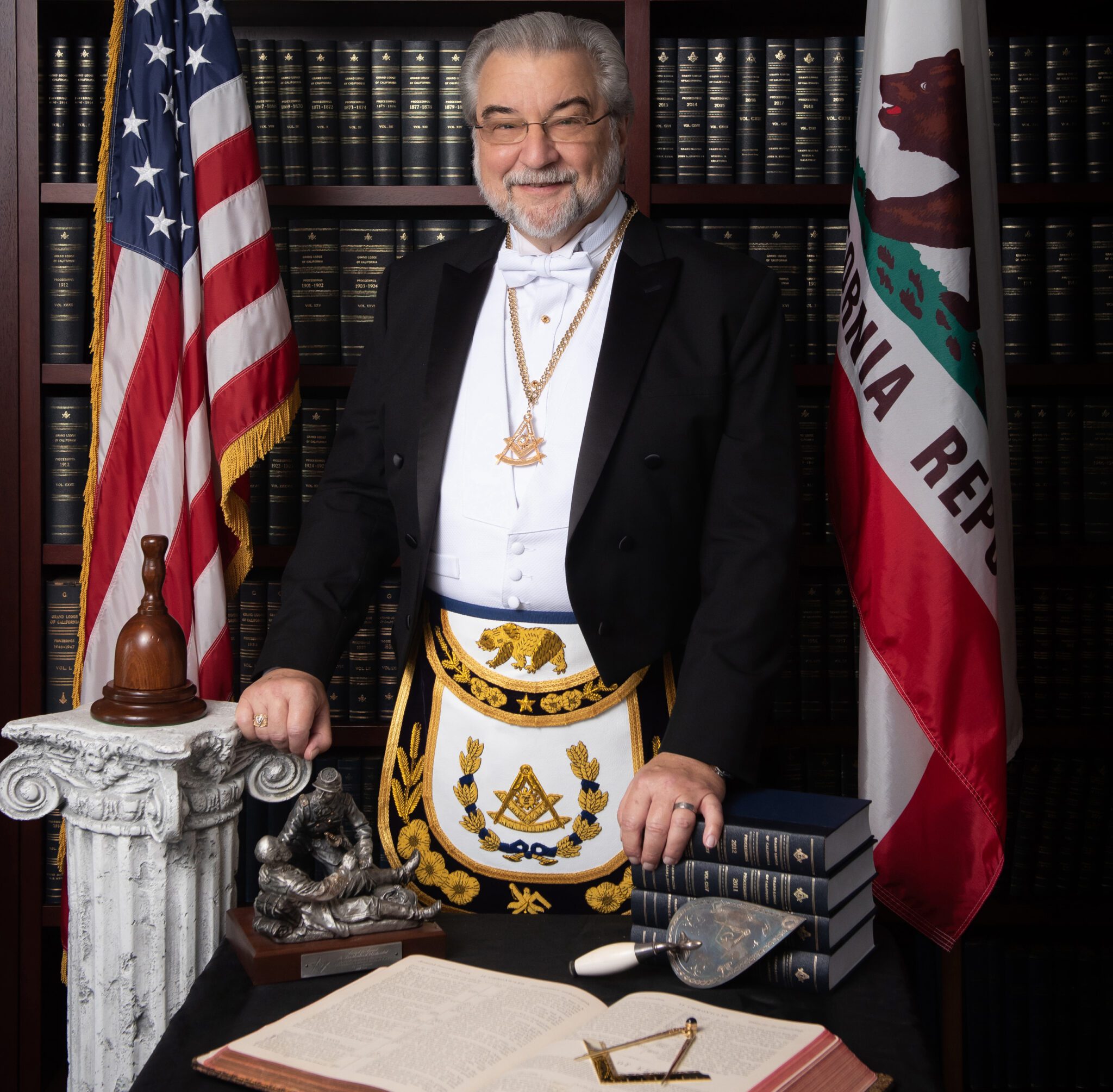

Grand Master Randall Brill reflects on 125 years of history and progress at the Masonic Homes of California.