The Masonic Homes of California: 125 Years and Still Growing

This June, the Masonic Homes of California celebrates its sesquicentennial—and reflects on its next chapter of life.

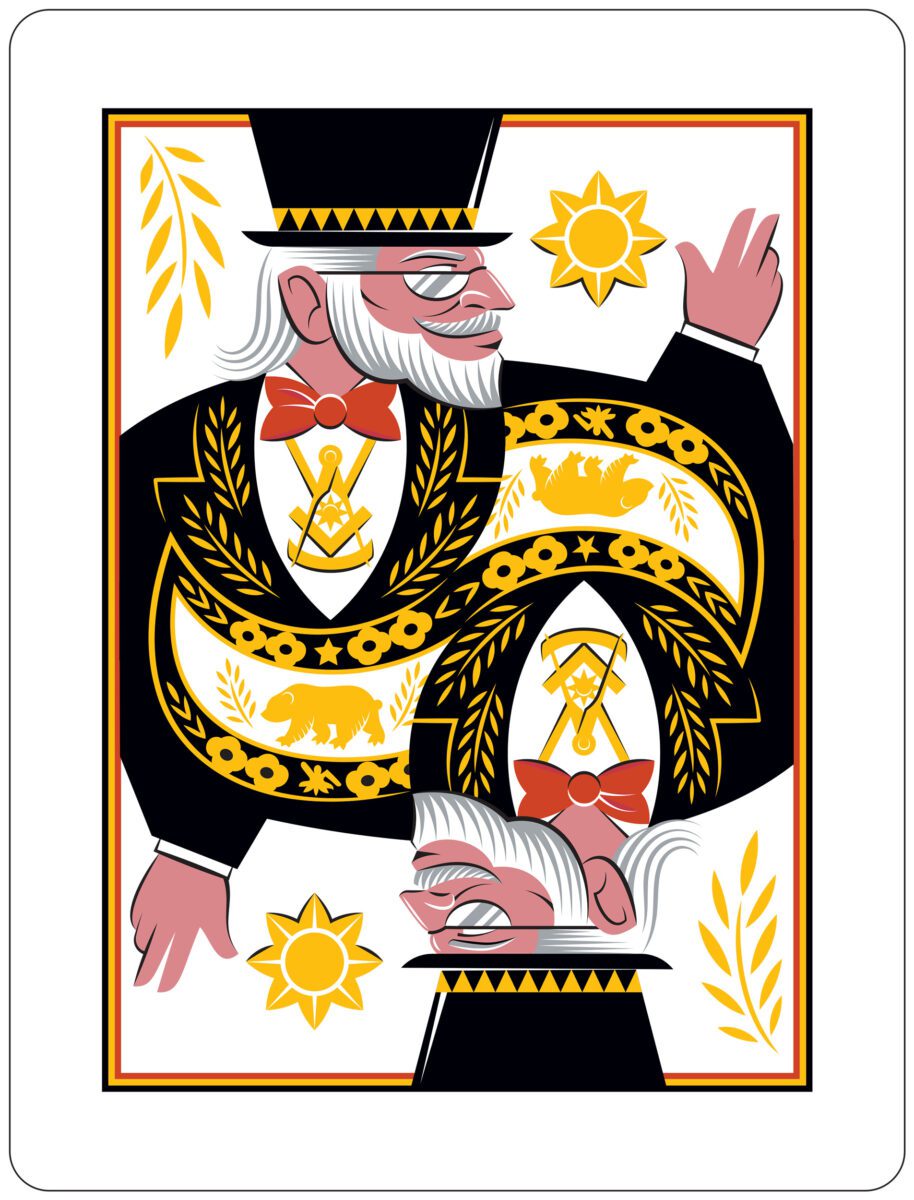

The man in the top hat commands the attention of his audience. He recites a speech that was passed down to him through generations, mouth to ear. He invokes esoteric wisdom and alludes to its mystical origins in the east. Then he takes his wand, taps the hat twice, and runs through a greatest-hits show of performance magic: the coin behind the ear, the rabbit in the hat, and, the fundamental act for any magician, the cups and balls.

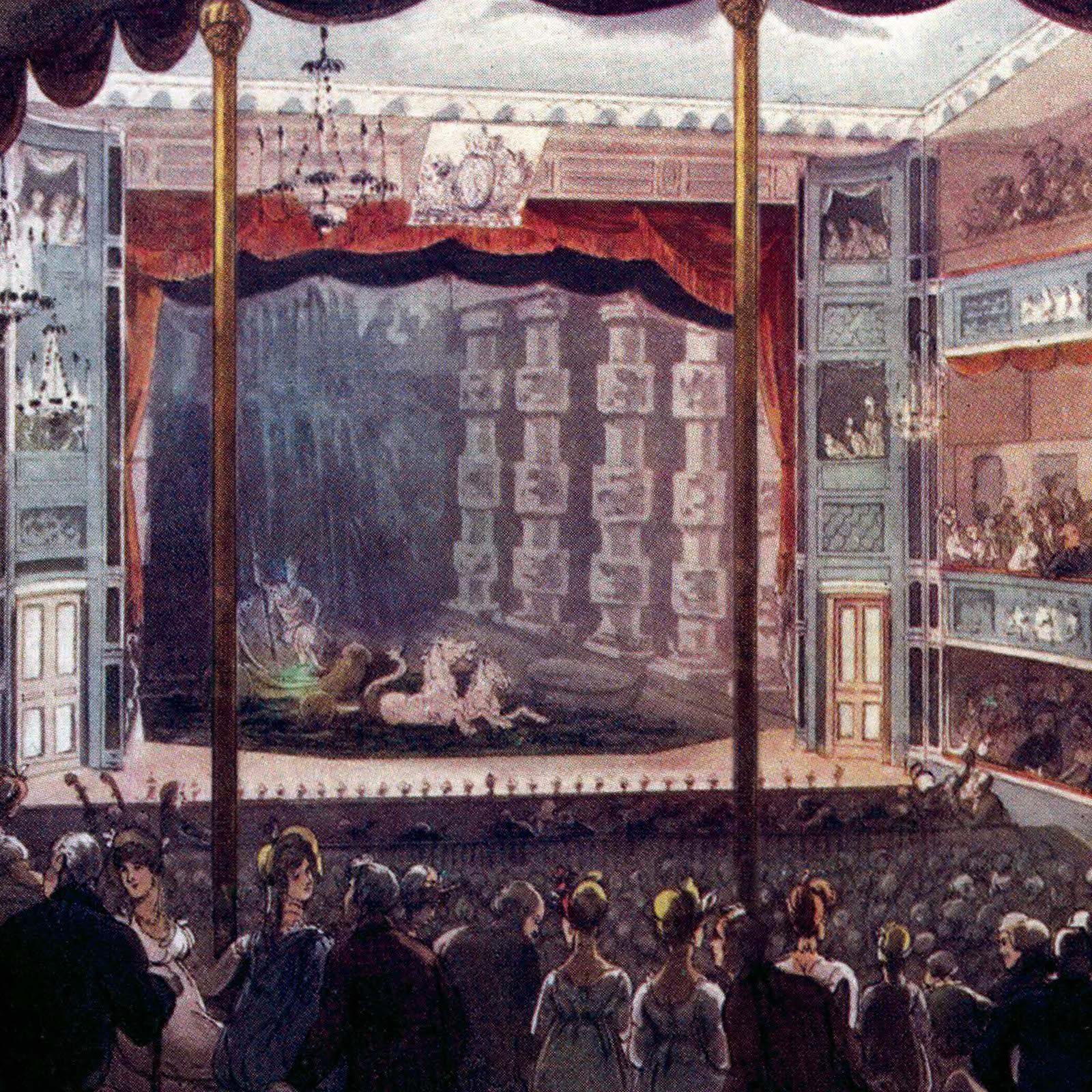

The parallels between Masonry and magic are clear to anyone who’s sat in a lodge room during a degree conferral or been astonished at a performer’s card trick. Both, of course, cultivate an air of secrecy and mystery. Both rely on sensory experience to make an impression on the mind. And both require a certain showmanship and panache to deliver a truly memorable experience. Perhaps most important, they share some significant membership overlap: virtually every one of the most celebrated magicians of the past 200 years have been Freemasons.

Why such a close connection? Those with an intimate knowledge of magic and Masonry say the two crafts share several similarities. “They have their own language,” explains Ralph Shelton II, the grand chaplain of the Grand Lodge of California. In addition to his work as an attorney, Shelton is a lifelong magic performer, and one of the founders of California’s first magicians’ affinity lodge, Ye Old Cup & Ball № 880. “Everyone loves the feeling of wonder,” he says. “People love to be amazed. Not fooled, but amazed.”

Masonry and magic each feature a long fraternal history. Like Masons, magicians have for generations gathered in clubs and societies of performers around the world. In fact, many of the hallmarks of membership in a Masonic lodge—the initiations, rituals, handshakes, and even funerary rites—can be found in groups like the International Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Magicians, to which the great Harry Kellar, Howard Thurston, and Harry Houdini all belonged. All three, incidentally, were proud Freemasons.

That magic and Masonry connection was acknowledged by one Masonic publisher with a subtle sense of humor. In the early 20th century, the Allen Publishing Company of New York published ritual ciphers with fake titles meant to throw off curious snoops, titling one Magicians’ Magic Movements and Ceremonies. Rediscovered by the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library in Massachusetts, the cipher opens with one page describing a fake magic-sword ritual. Then, without explanation, it jumps into the seeming gibberish of a ritual cipher book.

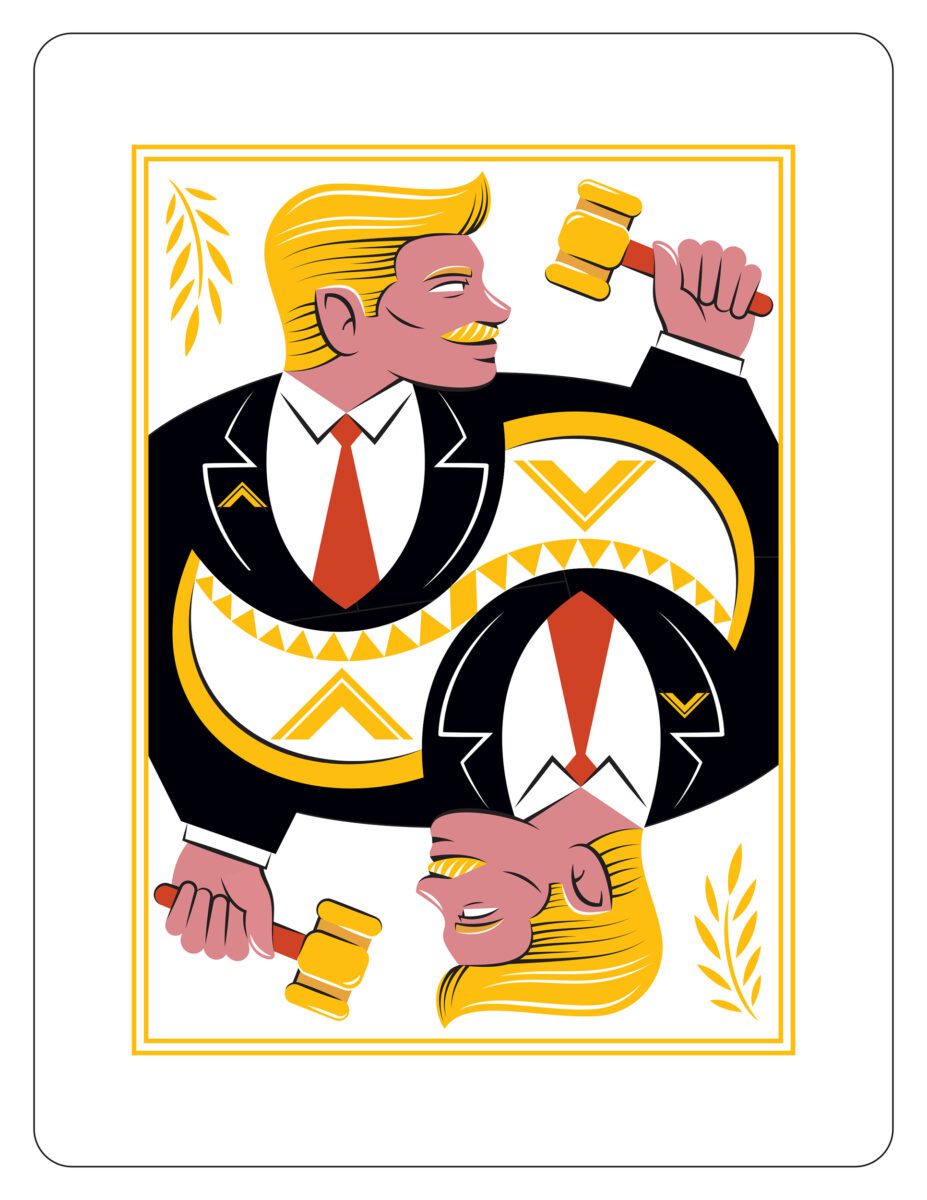

It’s a fitting sleight-of-hand trick, says Randy Brill, the grand master of California. Brill, too, has performed magic his whole life, and still counts himself as something of a semi-professional. “Most of us dabble in magic as kids, and some of us never grow up,” he explains. “Mystery has always attracted the human brain. We want to see something that mystifies us, something we can’t easily understand.”

Brill and Shelton are two of the organizers who will speak at the 2023 Masonic Symposium on June 28, titled Harry Houdini: Master & Mystic. The event pays homage to the Mason, magician, and Hollywood figure who perhaps did the most to bring performance magic into the public consciousness.

Houdini, of course, is practically the patron saint of Mason-magicians. He pushed the boundaries of the field, combining stage magic, parlor magic, illusion, and escape acts in his most celebrated performances. In an era long before television or social media, Houdini was a masterful marketer and showman who knew how to garner publicity. What’s less known about him is that Houdini was a committed Mason. He was initiated and raised in 1923 at St. Cecile Lodge № 568 in Manhattan (which is still active today), performed at Masonic benefit shows, and even received a traditional Masonic funeral.

The symposium won’t be the only Masonic fête honoring Houdini this year. In July, the Invisible Lodge International is hosting the Harry Houdini 100th Masonic Anniversary charity fundraiser at the Long Beach Scottish Rite Center. The event will include a midnight séance and a world-record attempt for the most simultaneous escapes. The Invisible Lodge, founded in 1953, is open to Masons around the world and styles itself as an “honorary association of Masonic magicians at work under the jurisdiction of the known and unknown world.” Unlike the Cup & Ball group, it isn’t a formal Masonic lodge, but rather a club and venue for Mason-magicians to connect and swap secrets of the guild.

William (J.R.) Knight is the president of the Invisible Lodge and also a California Mason at S.W. Hackett № 574 in San Diego. “I’ve been studying like crazy,” he says of the mass-escape act. Knight says he’s still tweaking the details of the event, and toying with a novel fundraising possibility. “What if your spouse is there with you at the escape, and she donates something extra so you don’t get out?”

What is it that’s so appealing about an act of illusion? Why do normally rational people—especially Masons, whose teachings are grounded in the seven liberal arts and sciences—delight in witnessing feats that fly in the face of the laws of physics?

Gustav Kuhn attempts to answer that question in his book Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic. Kuhn is a professor at the University of London and a magician with the Magic Circle there.

He speculates that magic acts might actually serve a role in cognitive function—namely, allowing us to hold contradictory beliefs. Kuhn suggests that “magical thinking” is innate in humans, dazzling us as babies playing peekaboo, and then confounding us as adults gambling at a casino even when we know the odds are stacked against us.

In fact, it’s often those with the greatest interest in science and order who seem most pulled toward magic acts. At least that’s been the case for Brent Morris. Morris, who will present at the June 28 symposium, is a 33rd degree Scottish Rite Mason and editor of the Scottish Rite Journal and also a former math major who led the cryptological mathematicians’ program at the National Security Agency. He holds what might be the world’s only doctoral dissertation on the subject of card shuffling.

Morris uses math to deconstruct card tricks, including “the perfect shuffle,” in which a performer restores a shuffled deck to its original order. Morris recalls meeting an esteemed scholar interested in the perfect shuffle who assumed it was only an academic curiosity, something that couldn’t be done in real life.

(There are 8×1067 ways to sort a deck of 52 cards— that’s 8 followed by 67 zeros.) “I had a deck of cards with me, I shuffled them, and 10 seconds later I had re-interlaced them to the original order,” Morris recalls. “It never occurred to him that you could actually do that.”

That instinct to break down seemingly supernatural acts into replicable components is common to nearly all magicians. In fact, Shelton says, there may be no more determinedly rational, critical thinkers out there than magicians. Call it the credo of an honest liar: Many famous magicians have made it their mission to expose performers who blur the line between illusions and miracles. Houdini, James Randi, and Penn & Teller, for example, have all aggressively exposed performers who claimed divine intervention. Houdini even commissioned an unpublished manuscript by H.P. Lovecraft called The Cancer of Superstition.

So, beyond their parallel fraternal histories, the similarities in custom, and the many significant figures they share in common, some practitioners speculate that perhaps Masonry and magic share a more spiritual sort of kinship.

That instinct to break down seemingly supernatural acts into replicable components is common to nearly all magicians. In fact, Shelton says, there may be no more determinedly rational, critical thinkers out there than magicians. Call it the credo of an honest liar: Many famous magicians have made it their mission to expose performers who blur the line between illusions and miracles. Houdini, James Randi, and Penn & Teller, for example, have all aggressively exposed performers who claimed divine intervention. Houdini even commissioned an unpublished manuscript by H.P. Lovecraft called The Cancer of Superstition.

So, beyond their parallel fraternal histories, the similarities in custom, and the many significant figures they share in common, some practitioners speculate that perhaps Masonry and magic share a more spiritual sort of kinship.

Centuries ago, the line between magic and science was not so clear or well defined. So-called “natural magicians” of the Renaissance era blended concepts of metaphysics, alchemy, and magic. It was into this proto-scientific hothouse that many of the themes found in “speculative” Freemasonry were born. Historically, even some esteemed scientists dabbled in “the other magic.” Consider Isaac Newton, an icon of science and the Enlightenment and a president of the Royal Society. Only after Newton’s death was it discovered that a substantial portion of his manuscripts dealt with alchemy and the occult. John Maynard Keynes, who purchased Newton’s private writings, was compelled to observe that, “Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians.”

Even defining magic is no easy task. It’s a loaded word with contested meanings. Some magicians bristle at the word magic and prefer the term illusion. Others embrace the word but are loath to acknowledge other types of magic. Justin Sledge, a scholar in Western esotericism, observed that the word magic has historically been used to “other” those with divergent views, denigrating them by implying that they trade in sorcery or trickery. (Consider how “magical” elements of gnosticism or voodoo are used to delegitimize those spiritual traditions.) Modern magic, whether we call it “stage magic” or “performance magic,” might never completely shake off those less-than-reputable vestiges of its past.

Masonry was not always so distant from “the other magic.” Arthur Edward (“A.E.”) Waite, who was already an established Masonic writer and poet, produced the most recognizable tarot deck still popular today, the Waite-Rider-Smith tarot. The tarot images of the Magician and the Fool that probably leapt to mind when Carl Jung sought to articulate the “collective unconscious” were in fact produced by a Mason. The founders of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which influenced many later magical orders, were all established Masons, including William Robert Woodman, William Wynn Westcott, and Samuel Liddell Mathers. Even the founder of modern Wicca, Gerald Gardner, was an established Mason in the UK. “Misunderstood and maligned” is how Carroll “Poke” Runyon describes the public perception of ceremonial magic. Runyon is a California Mason at Culver City-Foshay № 467. “Magic is transformative,” he says. “Americans are enamored of superheroes and comic books. Being a magician is a way for a person to feel like, and not pose like, a superhero.”

Likewise, the magician of the tarot deck is said to represent potential, manifestation, and transformation. These are all central elements of the Masonic experience. In The Commodification of Ritual, Andrew McCain describes what groups like the Masons offered initiates during the golden age of fraternalism: “Rituals offered an escape into an ideal masculine world where a common man could don the regalia of a Grand Potentate and take part in the pageantry of a recalibrated social order.”

Magic, whether as a staged illusion or in the supernatural sense, likewise rearranges our sense of order. The performer is able to control the seemingly uncontrollable. Ritual offers a similar kind of magic of its own. The Masonic ritual, which is fixated on precise movement and memorization, offers the promise of an invisible transformation. The anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski said of ritual and magic, “Magic is to be expected and generally to be found whenever man comes to an unbridgeable gap, a hiatus in his knowledge or in his powers of practical control, and yet has to continue in his pursuit.”

Whether it’s Houdini escaping a water tank or a costumed amateur pulling out your queen of diamonds from his deck, the magician is able to command an aura of wonder. They pierce the veil of perception, promising us a fleeting glimpse into what might be on the other side. Both the Mason and the magician, then, can be best described as seekers—those wishing to see more, to go beyond, to push the limits of their perception. Like the Masonic initiate, they await the moment of illumination from the proverbial darkness. As the magician says, Abracadabra!

ILLUSTRATIONS BY:

Luis Pinto

This June, the Masonic Homes of California celebrates its sesquicentennial—and reflects on its next chapter of life.

In Santa Cruz, a historic Masonic getaway prepares for its 100th anniversary while maintaining a unique ownership arrangement.

For 200 years, magician Richard Potter—once the most famous performer in America, and a Prince Hall Mason—has kept the public guessing.