In Masonry and Magic, Blending Illusion and Wonder

For generations, the world’s greatest magicians have found a second home in Masonry. Why have Masonry and magic shared such a close connection?

All his adult life, Richard Potter demonstrated a mastery of misdirection. He was a showman, so first and foremost he needed to call attention to himself; hence the flowing robe, the wig and costumes, the fine carriage and handsome matched horses, the life-sized, carved wooden human figures standing on pillars before his house, the fastidious dress and exemplary manners. But he was especially a magician and a ventriloquist—a sleight-of-hand, sleight-of-voice man—so he also needed to direct attention elsewhere: you were to see or hear what he could do, but you were not to understand how he did it.

He was very, very good at what he did. For many years Potter was the foremost ventriloquist in America, and the most celebrated magician as well. Indeed, he was the most famous American entertainer of any kind: there was no actor or vocalist or musician in the country who could even come close to Richard Potter’s renown. It wasn’t just secondhand fame, either, the kind that could be spread by stories from the daily newspapers of the large East Coast cities and republished as entertaining filler in the weeklies of remote little towns, rumors from a wonderful world that the provincial readers were unlikely ever to experience. While Richard Potter always made his home in New England, his tours took him across the length and breadth of the nation. Wherever you lived in America, even if you had not yourself attended at least one of his exhibitions, you probably knew people, perhaps even many people, who had. When he died, in 1835, he had become a national icon.

Nearly 200 years later, then, why does Potter’s name not ring out louder? How have we managed to remain so ignorant of this immensely significant fact? Simon During’s argument clearly applies here: Potter’s situation in the apparently trivial, seemingly ephemeral world of “entertainment magic” has blinded historians not only to his significance but even to his presence. For almost two hundred years, Richard Potter, master of misdirection, has been hiding in plain sight.

The following is adapted from Richard Potter: America’s First Black Celebrity, by John A. Hodgson, with permission from University of Virginia Press.

Richard Potter was not only the most famous American entertainer of his time; he was also the most famous Black person in America. It was not a designation that he had sought. He was very aware of his racial status and very sensitive to the injustices and denigrations that in America inevitably attended it; he was deeply embedded, furthermore, within the Black community of Boston and within a network of its Black leaders who were working to bring their community’s needs and concerns into the public eye. As an entertainer, however, he needed to keep his public persona apolitical and uncontroversial. He made his living by amusing and entertaining; as he knew full well and had often had occasion to confirm firsthand, he simply could not afford to fret his audiences (the vast majority of whom were white) or lose many of his venues by complicating his appeal with any allusions to his racial identity.

As a mulatto, the son of a Black mother (formerly a slave) and a white father, Richard Potter appeared to others to be whatever they already understood him to be or anticipated he would be— a dark-complexioned white man, a light-complexioned Black man, or perhaps a West Indian (i.e., Creole) or East Indian (Hindu). Because he could be and so readily was taken to be white, the assertion at the beginning of this section requires a qualification: although certainly Richard Potter at the height of his career was the most famous Black person in America, it is also true that most of his audiences were not sure that he was Black. They knew him firsthand as an amazing ventriloquist and magician; beyond that, they believed various things about him simply because they had been taught or encouraged to believe them.

The Black American who in 1829–30 became for a while perhaps even more famous than Potter was his African Lodge Masonic brother and very possibly his friend David Walker, whose powerful Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829), a biblically grounded denunciation of slavery, called for Blacks to resist it and whites to recognize its immorality. From this point on, most Black Americans who gained a national reputation, such as Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northrup, and Harriet Tubman, did so in the context of the struggle against slavery. For all of them, their blackness was an important reason for their fame.

Potter is unique on this list by virtue—and this is a remarkable, even bizarre, fact to note, given his profession—of his very ordinariness. Put simply, he was not controversial; he was not a participant or an instrument in a grand societal argument, save for the old, familiar one about the value and respectability of theatrical entertainments. But more importantly than this, he was always, always associated in people’s minds—often at a very impressionable age, for children made up large parts of his audiences— with laughter, mystification, and delight. His lifelong practice was to “sweep away care” for an evening by amusing, astonishing, and thrilling his audiences, making them laugh and wonder and give themselves over to the varied pleasures of his exhibition; he brought the gift of comic catharsis.

A tribute to Richard Potter published nearly 40 years after his death (by an editor who firmly believed that Potter was “a native of the East Indies”) gives a sense of the audience experience, recalling that “both old and young were wrought up to the greatest pitch of excitement” by Potter’s magic tricks: “Among the ignorant the magician was known as ‘Black’ Potter, and the most supernatural powers were attributed to him. He was said to be in league with the devil. Superstitious mothers would endeavor to frighten their children into obedience by threatening to give them to ‘Black’ Potter, but this ruse was robbed of any effect after the little ones once attended an exhibition of the magician, for they invariably came away delighted with the mysteries of the show and in love with the conjuror himself.”

“Black” in its racial sense was often still there in the background of Potter’s legend, of course, as in that 1874 recollection. But that is the point: in the background is just where Richard Potter was careful to keep it. He did not deny his racial identity, but neither did he, in his dealings with the public, foreground it. He did not care to be pinned down about his origins or “found out” by those who did not know him well. Those who persisted in such inquiries would eventually discover how very skillful his misdirecting could be—or, even better, would never even realize they’d been fooled.

It would seem, moreover, that Potter took care to be inconspicuous in his private life. Boston at this time was a center for nascent reform and protest activities affecting Blacks, focusing especially on community volunteerism, education, and the antislavery movement. Potter seems never to have played a public role in any of these activities. Although this was first of all simply a function of his frequent lengthy absences from Boston, it was probably a matter of policy on his part as well, for we know both that he was eventually a figure of real prominence in Boston’s Black community and that he was quite sensitive to the issues of race that so severely defined and confined him. But a public entertainer only loses by alienating any of his potential audience unnecessarily; it behooved him professionally to be ingratiating, apolitical, and uncontroversial.

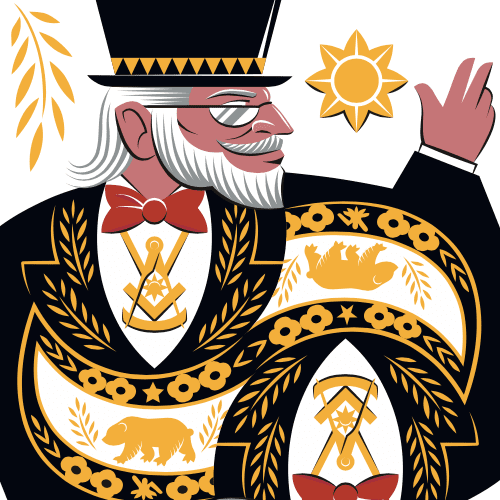

There was one fraternal organization in Boston, however, in which Potter was significantly engaged. He was a member, eventually a very prominent member, of the African Lodge of Boston, eventually to become known as the Prince Hall Grand Lodge, the first Black Masonic lodge in America. Founded by Prince Hall, a free former slave who had been introduced into Freemasonry by British soldiers in Boston in 1775, African Lodge No. 459 received its charter from the Grand Lodge of England in 1784 and soon became an important Black social organization. It fostered sister lodges in Philadelphia and Providence in 1797, and Hall himself became a prominent advocate for Black rights and education, heading a petition seeking the establishment of an African school (1787) and another complaining of the kidnapping and enslaving of free Blacks (1788). For decades thereafter, the memberships of the African Society (a benevolent group) and the African Lodge and the advocates for African schools in Boston were significantly overlapping groups.

Hall died in late 1807. Potter petitioned the lodge for membership in early November 1811 and received his first three Masonic degrees in early December 1811. Clearly his involvement with the lodge could be only irregular over the following years, since he was so infrequently in Boston during 1815–17 and completely absent from late 1818 through mid-1823. But just as clearly it never lapsed, for upon his return to New England in 1823 he soon assumed a position of prominence in lodge affairs.

The lodge’s records for this period were often quite scanty and irregular in the first place, and then damaged over the course of time even to the point of frequent illegibility. Despite those limitations, however, these records contain a rich and unique lode of information about social connections among the more prominent members of Boston’s growing Black community. Lodge membership offered not only social engagement but also a venue for politically inclined activism, for Prince Hall had believed that Black Masonry should work to serve the Black community, “doing what we can to promote the interest and good of our dear brethren that stand in so much need in such a time as this.” Membership also required commitments both of time and of money; the latter effectively meant that only regularly employed and at least modestly established men would be able to pursue it.

Despite the paucity and obscurity of the African Lodge records for the early years of Potter’s membership, and the dismaying silence of those records on many points of basic information, it is possible to derive from them a list of some 20 men who were fairly active in the lodge at this time (1810–13). It is safe to say that Richard Potter would have known all of these men; and some of them must have been real friends, or else he would never have pursued membership in the first place. These men seem obscure to us today, because their names never featured prominently in the newspapers and books of white Boston and because their race inevitably confined them to a handful of service or unskilled professions (barber or hairdresser, bootblack, laborer, waiter), but they were known and even widely known in their own community.

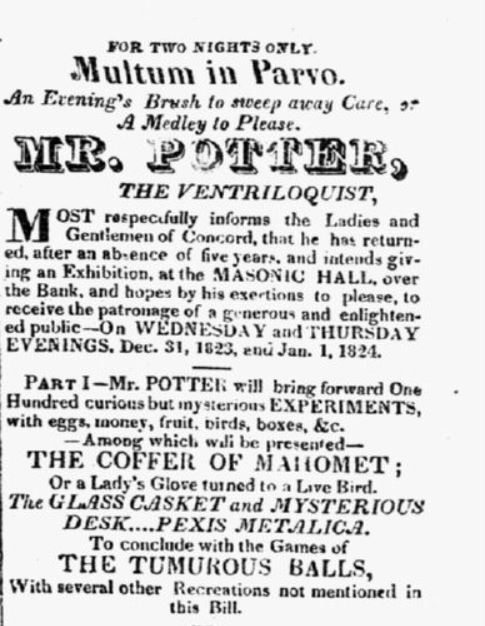

In 1808–14 Potter was just beginning to establish himself in his profession, and he was frequently on the road, away from his home. He moved comfortably among a set of respectable and sometimes well-connected white friends; he also fit comfortably into the Black community, in all its variety, and was a friend of many of the most prominent and outspoken members of that community. Richard Potter clearly regarded his Masonic affiliation as an important feature of his public persona, and he sometimes invoked it in his publicity. Like many contemporaneous white entertainers who were Masons, he occasionally incorporated Masonic emblems or allusions into his printed advertisements. Masonic iconography appears, in fact, in some of the earliest Potter broadsides that are extant. In one of these (probably dating from circa 1809), headed by a large, bold, and ornate “Mr. POTTER,” the gap between “Mr.” and “POTTER” is filled with a small woodcut: it depicts a personalized sun and moon looking down on a plank or tabletop on which are assembled a collection of distinctively Masonic items (compass, square, mallet, trowel, Bible). In another, probably somewhat later (circa 1818), the gap between a large “Mr. and Mrs.” and “POTTER” is this time filled by a very large Masonic compass, in the iconic upright pose. These woodcuts served as unmistakable signs to their beholders that this Mr. Potter was a Mason, a person or respectability, and a believer in universal brotherhood.

ILLUSTRATION CREDIT:

Interior Of Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London, Circa 1809/Wikimedia

Book Cover Courtesy Of Uva Press Courtesy Of Historic Northhampton

Detail Of Book Cover Courtesy Of Uva Press

For generations, the world’s greatest magicians have found a second home in Masonry. Why have Masonry and magic shared such a close connection?

Pilares del Rey Salomon joins California’s growing ranks of Spanish-English Masonic lodges.

At Ye Olde Cup & Ball No. 880, California’s first affinity Masonic lodge, members are dedicated to mastering two crafts: Masonry and magic.