Donor Profile: Hercules Valdez

A former priest on what his world travels have taught him and how Masonic relief ties it all together.

There’s a scene toward the end of the first season of the AMC TV series Lodge 49 that may strike a familiar chord with many Masons. In it, Dud, an eager if aimless initiate to the fictional Ancient and Benevolent Order of the Lynx, and his mentor are explaining the appeal of the lodge to an enigmatic real estate developer known as the Captain. “So do you do weird, secret [stuff]?” asks the Captain. “Like robes and candles and Latin?”

Ernie, the pragmatic leader of the lodge, demurs. “No, no, no, it’s not like that. It’s a social club. Beer and softball, that kind of thing.”

“What are you talking about?” Dud interjects. “It’s exactly like that!”

That juxtaposition between the banal and the sublime is at the heart of Lodge 49 (currently streaming on Hulu). For series creator Jim Gavin, that contrast was fertile territory for a humorous, if ultimately loving, exploration of man’s search for meaning. Here, Gavin expands on his fraternal influences, the history of Long Beach, and creating the perfect lodge setting.

California Freemason: You’re not a Mason yourself, but you seem to really nail so much about belonging to a lodge—for better and worse. How were you able to tap into that?

Jim Gavin: First, I’ve had a longtime interest in esoteric societies and the Western tradition of esoteric thought. But I think a lot of Lodge 49 was wish fulfillment, in a sense, in a world where our lives are mediated by apps and social media. That can be isolating. So there’s this desire to find a place where you meet in person, in a dedicated space. I’d spent some time in Elks lodges and done my research, talked to a bunch of people. And I thought the beauty of it was this notion that in your daily life, you have whatever job you have, and then you go to this place and you’re recognized in a completely different way. So in the show, a plumbing salesman can be a “luminous knight.” I find that sense of grandeur in the middle of our ordinary lives really beautiful, and I wanted to re-create that atmosphere.

The fictional Lynx lodge includes both men and women. There’s also a really diverse group of people there—young, old, Black, white. Was that intentional on your part?

It was in some ways. But for any realistic portrait of California, and Long Beach in particular, it’s a diverse place. And there’s a long history in the African American community of Masonic membership and lodges throughout the 20th century, so that’s all there. Again, it was a bit of wish fulfillment in terms of having men and women side by side—even the Elks weren’t open to women until the 1970s or ’80s. I wanted to open that up. But it wasn’t about ticking boxes. It was natural for telling a story about Long Beach.

Long Beach looms really large in the series as this downtrodden, postindustrial setting. That’s kind of a mirror of the lodge, right, in that they’re both past their heyday?

Long Beach after World War II had a massive membership in fraternal orders including the York and Scottish Rite. And it had the largest Elks membership in the country. There was this total middle-class prosperity being reflected in these lodges. And as that wave crested, it started diminishing. The show tells the story of that lost heyday and the downturn, and then the hope that a younger generation can come in and renew or refresh things.

Two of the main characters, Ernie and Blaise, embody the different promises a lodge makes. Ernie is into the camaraderie, and Blaise is into the mysticism. Which part speaks to you more?

They’re kind of the two parts of my personality, split. I definitely have a Blaise side and an Ernie side, and Dud is somewhere between the two. For me, it’s the joy of that high and low, side by side, all in one place. That feels natural to me as a storyteller. A lot of these traditions are a way of seeing the world through a different lens—a way of understanding the mysteries of the universe. One thing that’s lost from our lives is a sense of mystery, and that’s a major loss. There’s something about these places that restores that in a way that’s really fulfilling.

Is the number of the lodge a reference to The Crying of Lot 49? So much of the show feels like a Thomas Pynchon novel.

When I first wrote the script and imagined the world and the characters, it had a generic title, like The Lodge. But I like specificity in a title, and all these lodges have a number. The first number that came to mind was 49. I’m a Pynchon devotee, so obviously that influences things. The Crying of Lot 49 is such a great SoCal novel. And yeah, it’s got so much of that goofball conspiracy thing. It’s an homage to the big guy.

You play around a lot with stereotypes of groups like the Masons being part of the Illuminati. But in your show, the lodge members aren’t all-powerful at all—in fact, most of them are broke and barely getting by.

A phrase I like to use is “conspiracy from below.” The people in the lodge, they have no control. They’re nickel and diming down there, but they’re also the keepers of this grand tradition. That’s what I love, that combination. I’ve always found the ideals of Masonry really beautiful. I took from that. And as we’re heading toward a deeper understanding of the lodge, we wanted to have fun with that. In the end, it’s just these guys trying to keep the doors open on this place they like being.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY:

Jackson Lee Davis/AMC

A former priest on what his world travels have taught him and how Masonic relief ties it all together.

For seniors at the Masonic Homes of California, moving in is an opportunity to focus on what matters most.

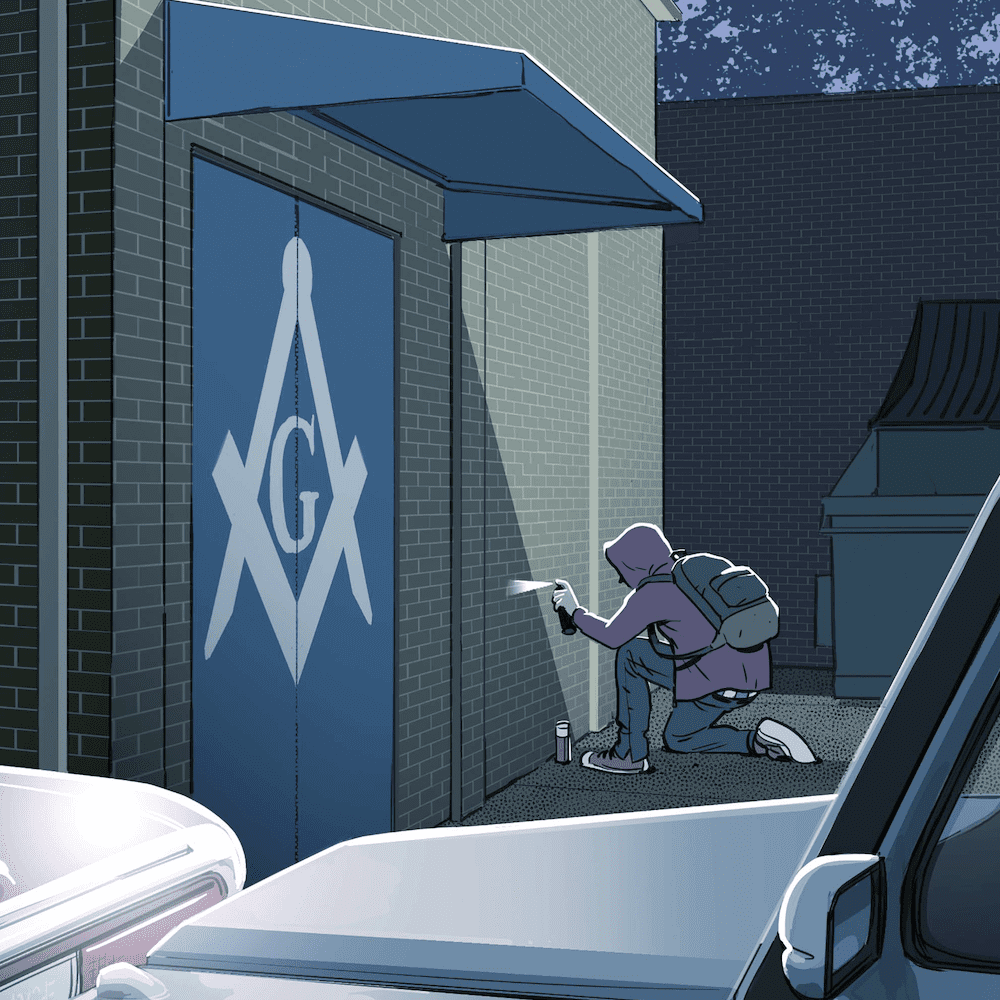

Could a piece of stencil art at Windsor No. 181 be a genuine Banksy?