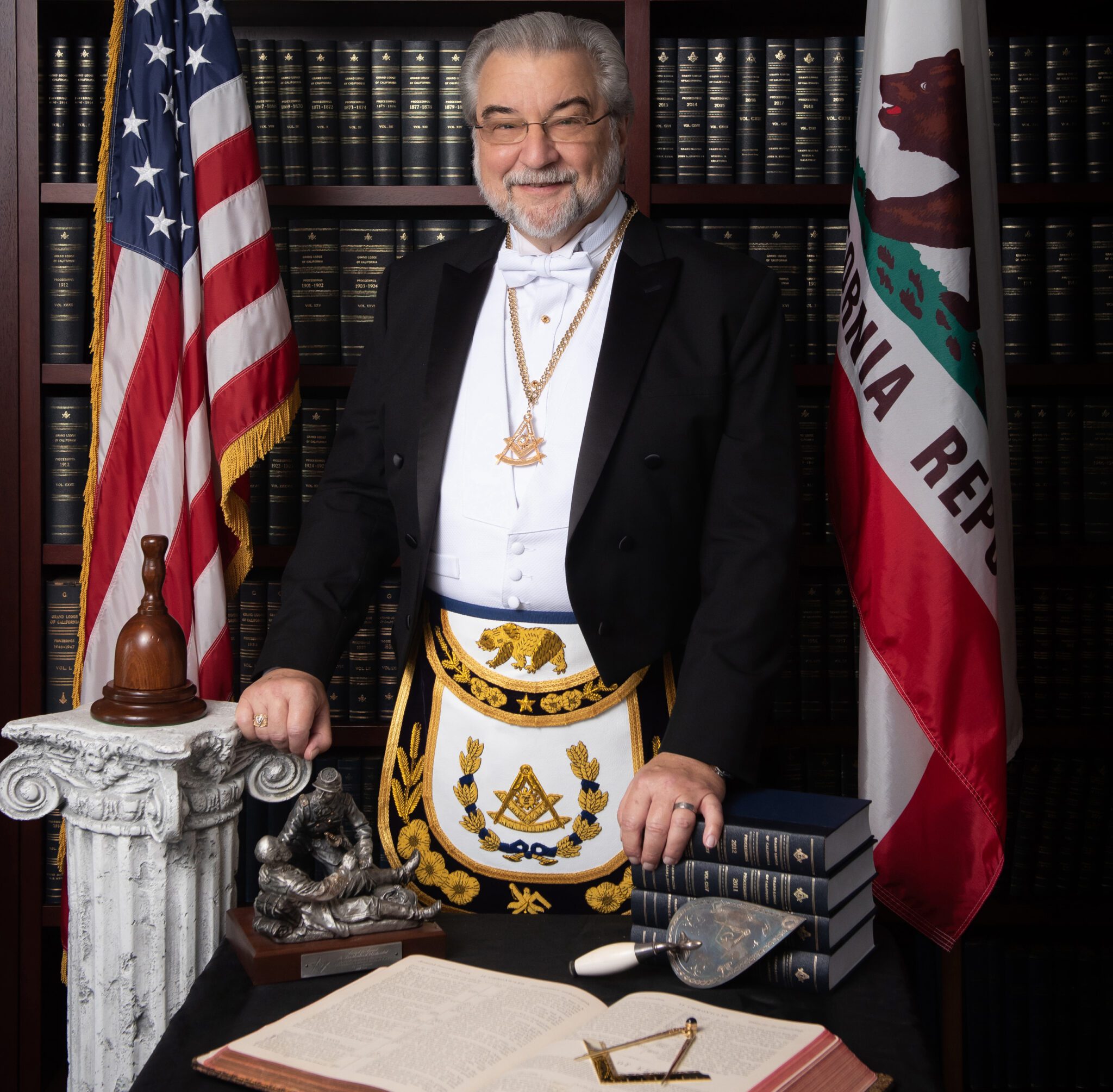

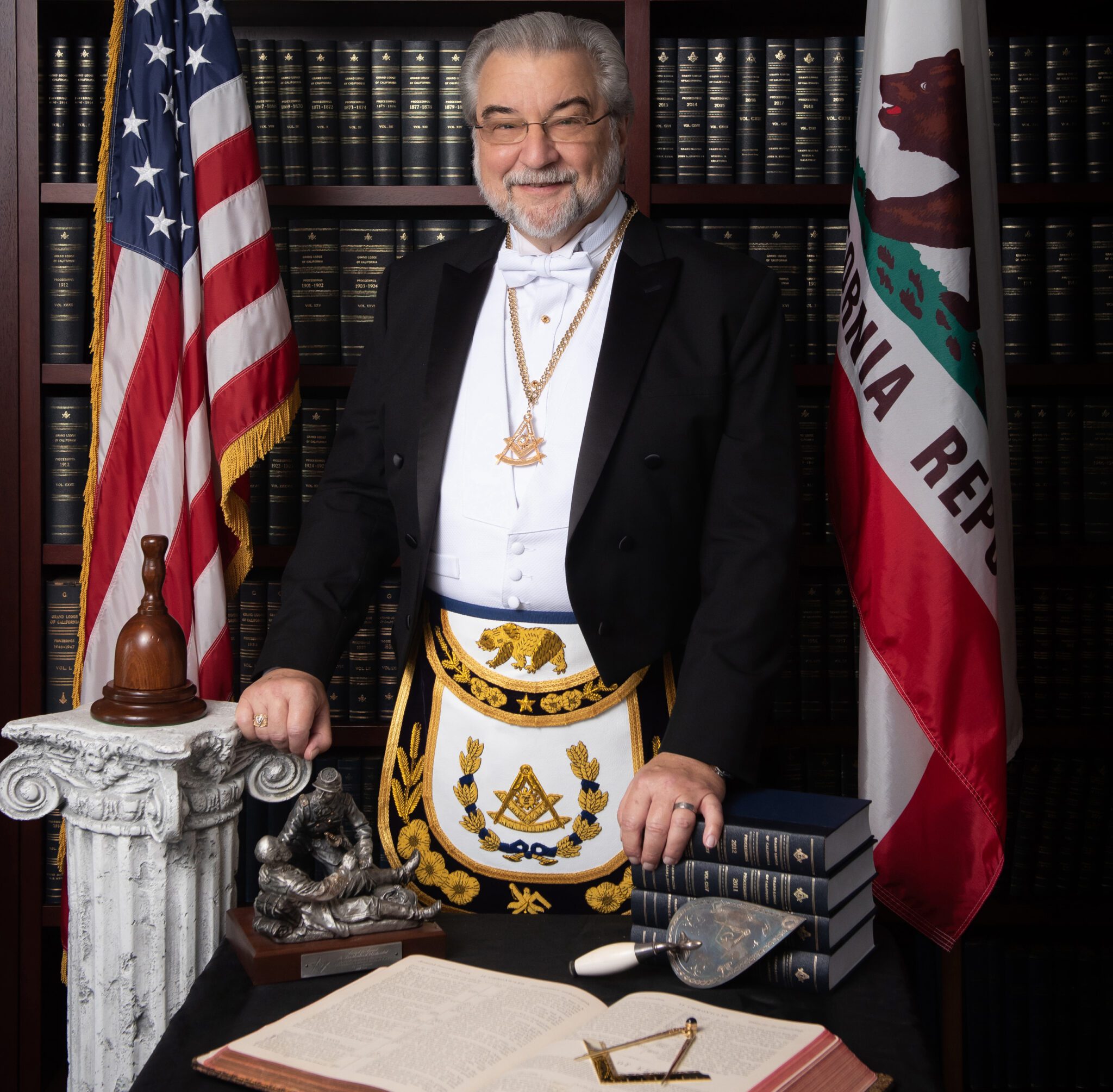

Grand Master Randy Brill: Starting Again

Grand Master of Masons of California Randall L. Brill explains how now’s the time for Freemasonry to begin again in California.

When the enigmatic image of a girl reaching for a heart-shaped balloon mysteriously appeared on the wall outside Sonoma County’s Windsor Lodge № 181 in December, it was instantly familiar to Patrick Muldoon, the first at the lodge to spot it. “Normally, if something were to be painted on our building, the response would be, ‘Let’s contact the city to come out and clean it off,’” Muldoon says. But this was a bit different. That’s because the image, “Girl with Balloon,” is one of the most famous works by one of the most widely known living artists, the street artist and activist known as Banksy. It also happened to be among Muldoon’s own possessions, albeit in scaled-down form. “I have thank-you cards that have that exact same image on them,” he says.

But could it possibly be authentic? The prospect seemed almost too tantalizing to consider.

As word of the stenciled girl spread, the lodge found itself playing host to dozens of selfie-taking visitors and fielding questions from reporters. Is-it or isn’t-it stories appeared across the web, including from local outlets like NBC Bay Area News, the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, and KCBS. “We’ve all seen graffiti on buildings and don’t think twice, but this one draws your attention,” Muldoon says.

Attention, yes. But also skepticism. Windsor, a sleepy town about 15 minutes north of Santa Rosa, would seem far outside Banksy’s usual milieu. Among his best-known works are pieces on the streets of London, Paris, and New York. More recent ones have appeared in the Palestinian West Bank and in Ukraine. “Washington, D.C. might get a little more attention than Windsor,” jokes Mark Azzouni, a trustee of the lodge’s hall association.

Also complicating the case for the work’s originality was its placement. The work w as installed on the back side of the lodge, facing a parking lot—not exactly the typical high-visibility placement that Banksy (and most other street artists worth their salt) would usually go for.

Still, lodge members couldn’t quite shake the idea that it might really have been put there by the artist himself. It wasn’t entirely out of the question: several of Banksy’s works have appeared in the Bay Area over the years—and even a world-famous art provocateur might reasonably take a side trip to wine country. Almost a decade ago, an authentic Banksy image of a rat in blue and red 3D glasses was one of three pieces found in the relatively unlikely locale of Park City, Utah. There was also the Masonic angle to consider. “People have talked about the relationship between Banksy, who is kind of anti-establishment, and the contrast of that with the Masons,” Muldoon speculates. Could the work have been a statement about Freemasonry, with its many ties to the founding of the republic (or its reputation for secrecy)?

Muldoon figured it was probably a long shot, but he enjoyed the buzz nonetheless. “I do love the attention it brings to our community and the lodge,” he says. “If people enjoy it, and enjoy taking pictures with it, I’m all for it.” And if it raised the profile of the lodge in the process, that seemed like an added bonus. (The lodge’s square and compass insignia is visible in many photos of the artwork posted online.)

In any case, the lodge and hall association weren’t taking any chances. Working with the Grand Lodge real estate division, the lodge reached out to its property insurer and submitted images of the piece to the online official authenticator of Banksy works. Meanwhile, the insurance provider connected the lodge to auction houses in London to help place a value on the piece, if it was in fact real.

As for how much it might be worth, the sky was practically the limit. Banksy’s best-known works have sold for as much as $20 million in the past, and even some seemingly immovable stencils have been carved out of buildings and sold for millions. Whether or not the image was legitimate, the lodge agreed it needed to be protected. “It fits right in, so I hope we figure out a way to protect it,” lodge member Randy Saxe said in January.

As the weeks went by, the lodge continued to check on the stencil, with a rotating cast of members taking turns driving by the building to make sure it wasn’t painted over or vandalized. “It kind of brought the lodge together,” Muldoon says. Even members who wouldn’t have known a Banksy from a Caravaggio found themselves growing fond of the piece. “It’s part of the story of our lodge now, whatever happens,” Muldoon said.

By mid-February, the official word had come down: the Windsor Banksy was a fake. The artist’s authenticators confirmed as much in a three-line email. “Unfortunately, the work you submitted is not a genuine work of art by Banksy. Apologies this isn’t the answer you were hoping for.”

So while the lodge was not, in the end, sitting on a pop culture goldmine, most members weren’t too broken up about it. The piece would remain regardless. “Just as if I had a copy of someone’s artwork in my house, it still leads to an emotion or a feeling or a discussion,” Muldoon says. “It’s art. If somebody sees beauty in it, that’s great.”

Above:

Lodge members Randy Saxe (left) and Patrick Muldoon pose outside Windsor No. 181 in front of the mysterious stencil.

PHOTOGRAPHY/VIDEO BY:

JR Sheetz

ILLUSTRATION BY:

Frank Stockton

Grand Master of Masons of California Randall L. Brill explains how now’s the time for Freemasonry to begin again in California.

For seniors at the Masonic Homes of California, moving in is an opportunity to focus on what matters most.

In Vancouver, a pair of lodges are reborn as mixed-use developments.