Member Profile: Aziz Yousef

Meet a San Francisco café owner giving back through Freemasonry.

Past Grand Master Russ Charvonia remembers exactly where he was on Highway 101 when he decided to pick up the phone and apologize. “My heart was beating fast as I dialed,” says Charvonia, who at the time was still coming up the fraternity’s ranks. “I thought, Is this the right thing to do? It’s going to make me look like a fool.”

A recent conflict at his lodge, Channel Islands No. 214, had been eating at him. To be fair, it was more like a one-sided war than a conflict, with Charvonia an army of one. Not long before, during a turbulent time, a new master had stepped in to lead the lodge. Right away, something about him set Charvonia off. To put it bluntly, Charvonia says, “I had made my mind up: This guy is a real jerk.”

This went on for months. Until one day, Charvonia witnessed an interaction between him and another member. It ran against everything he’d been telling himself. “He was treating this brother with such care and compassion,” he says. The old narrative crumbled. Charvonia realized that if there was any jerk in the lodge, it was him.

Now, speeding along Highway 101, he knew he wanted to do something about it.

When his fellow lodge member picked up the phone, Charvonia didn’t waste any time. “Worshipful, I owe you an apology,” he said. “I judged you when I shouldn’t have.”

On the other end of the line, the member listened. He gave Charvonia all the time he needed to say his piece. When Charvonia was done, he forgave him. And then he did him one better. He went on to become one of Charvonia’s most trusted advisers. It’s a lesson Charvonia thinks about whenever he sees members struggling with conflict. What if he hadn’t swallowed his pride and picked up the phone that day? What if he’d just let things take their course? “That phone call didn’t just preserve a relationship,” he says. “It built a foundation.”

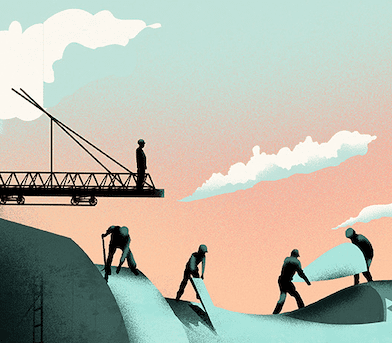

In any building’s foundation, minor cracks can eventually lead to major problems. It starts any number of ways—a mistake during construction, a catastrophic event, the simple wear and tear of time. If you spot a crack early, you might be able to repair it yourself. Let it go too long and the damage will almost certainly get worse. After enough time, it can bring down the whole structure.

In any building’s foundation, minor cracks can eventually lead to major problems. It starts any number of ways—a mistake during construction, a catastrophic event, the simple wear and tear of time. If you spot a crack early, you might be able to repair it yourself. Let it go too long and the damage will almost certainly get worse. After enough time, it can bring down the whole structure.

That’s the case with Masonic lodges, too.

“You can usually sense the minute you walk into a lodge if there’s conflict,” says Gary Silverman, past master of Saddleback Laguna Lodge No. 672. “It’s almost palpable. There’s a fracture. You can see it in the dining room. There’s a group over here and a group over there, and never the twain shall meet.”

Silverman should know. As a crisis management consultant, he’s made a career out of conflict resolution. He intervenes with businesses experiencing explosive growth or about to go under, helping CEOs and other leaders work through their issues to build healthier teams.

He now takes the same lessons for struggling businesses and applies them to lodges. At Masonic leadership retreats, he often gathers lodge leaders in candid, confidential discussions about the problems keeping them up at night. Over the years, he’s visited many of their lodges to facilitate conflict resolution.

As a result, he’s been around more lodge discord than most. He’s seen conflicts that started as innocent misunderstandings harden into grudges. He’s seen conflicts caused by the pressure a lodge experiences during a time of growth or change. He’s seen conflicts about money and status and personality clashes. More than that, he’s seen them start with someone who simply wants to be heard. “Interpersonal conflicts usually come from a common issue: Somebody has a desire to contribute and they’re not being allowed to,” he says. “Often all the person wants is to be listened to and have their opinion valued.”

Whatever the circumstances, take it from Silverman: Conflicts don’t just flare up at troubled lodges or growing lodges, old lodges or new. They happen everywhere.

No matter what the cause of such problems is, learning to address them is one of the most important issues a lodge faces. In membership surveys, Masons consistently say that issues related to lodge harmony—interpersonal relationships, politicking, bickering—are the greatest contributor to their overall feelings toward the fraternity. Those who feel heard and respected remain active; those who don’t tend to drift away.

For many lodge leaders, navigating the tangle of intralodge beefs isn’t just challenging—it can feel totally outside their skill set. Yet a lodge master’s greatest responsibility isn’t just balancing the books or organizing events; it’s maintaining lodge harmony. Luckily, Silverman says, the tools they need are all available within the context of Masonic teaching.

When Silverman meets with members who are at odds, he usually begins with a question: Why did you join? If members can focus on that shared experience, they might find the motivation to stick around and talk. “Both parties must be invested in a resolution,” Silverman says. In other words, they have to care enough about the relationship to begin the hard work of fixing it. For that to happen, they often need to recognize that they share a common goal. “That gets the focus where it needs to be.”

Once they agree to that, it’s a matter of following the lessons every candidate learns in the first degree: Meet each other on the level. Part on the square. Walk uprightly.

Of course, like most of Masonry’s lessons, this is easier said than done.

To mend a damaged relationship, a lodge needs the courage to sit down and talk about the problem. And for that to be successful, it might need some help from a skilled facilitator—or, at the very least, some practice with difficult conversations.

To mend a damaged relationship, a lodge needs the courage to sit down and talk about the problem. And for that to be successful, it might need some help from a skilled facilitator—or, at the very least, some practice with difficult conversations.

So in 2014, when he became grand master, Charvonia made difficult conversations something of a mission. He was troubled by the increasingly divisive rhetoric in the news and on social media; he knew that Masons could do better. So he devoted his grand master’s term to forming and launching the Masonic Family Civility Project, hosting discussion forums and sharing resources for promoting respectful, productive discourse between Masons and non-Masons alike.

The discussion model takes Masonic concepts like equality, tolerance, and brotherly love and puts them through their paces. It typically features a group of five seated in a half-circle, representing different viewpoints on a hot-button issue. The goal at the end of the 45-minute discussion isn’t to solve a problem or change anyone’s mind. It’s simply to practice hearing one another and responding with respect, even on a topic that makes everyone see red.

Charvonia applies the same strategies to help lodges navigate personal conflict. When he visits a lodge to talk through a problem, he begins by asking everyone to make a commitment to remaining civil. Then he opens up the floor. In the ensuing discussion, he chimes in occasionally, but only to keep things on track. He reminds members to restate what they’ve heard before rushing to respond. He coaches them to use “I” statements instead of sweeping declarations about others (or “you” statements).

Crucially, he asks everyone to allow for the possibility that they might be wrong. “How many times, with our kids, our partners, our lodges, does it become a battle to be right?” he says. “That’s not conducive to harmonious relationships. So much of getting along with one another is giving people the grace to be wrong.”

Many times, by the end of these conversations, Charvonia senses a shift. The more people feel heard, the more they’re willing to listen. The more they feel acknowledged, the less they care about winning. Charvonia sees members genuinely try to put themselves in one another’s shoes. Perhaps best of all, he watches their mutual respect deepen, even among those who remain on opposite sides of an issue. These changes may be subtle; reconciliation takes time. But for many, even a small course correction can point the way back to harmony. Oftentimes, the lodge may wind up stronger than it started.

“As Masons, we make a commitment to each other to do what it takes to build rewarding, productive relationships,” Charvonia says. “That’s all Masonry is. It’s how we can be more intertwined to achieve greater good for this world. It’s about relationships.”

Masonry talks a lot about how to build a lodge. It talks less about how to fix one. But the same tools for building are used to make repairs. Take the square and the plumb. They remind Masons to treat one another fairly and with respect. That’s the way out of almost any conflict. In times of turmoil, they’re more important than ever. “I’ve heard it said: ‘A lodge should be a place where armor is neither required nor rewarded,’” says Chris Smith, a district inspector and member of Peninsula No. 168. To Smith, that gets at the whole point of Masonic harmony. “For us to really be able to focus on improving ourselves and on the principles of the fraternity, we need the lodge to be a safe space,” he says.

Masonry talks a lot about how to build a lodge. It talks less about how to fix one. But the same tools for building are used to make repairs. Take the square and the plumb. They remind Masons to treat one another fairly and with respect. That’s the way out of almost any conflict. In times of turmoil, they’re more important than ever. “I’ve heard it said: ‘A lodge should be a place where armor is neither required nor rewarded,’” says Chris Smith, a district inspector and member of Peninsula No. 168. To Smith, that gets at the whole point of Masonic harmony. “For us to really be able to focus on improving ourselves and on the principles of the fraternity, we need the lodge to be a safe space,” he says.

When a lodge fractures, it’s hard to feel safe. Members’ instincts turn to fight or flight. Instead of opening up, they withdraw. For a time, they lose their safe space. But more than most, Masons have the tools to repair something that’s broken—including themselves. In these moments, Smith turns to the symbol of the rough and perfect ashlars, that lifelong work in progress. “There are so many lofty ideals for us to struggle toward,” he says. “Everyone has their own ashlar that they’re working with, trying to knock off all the pointy edges that cause injury to others.”

Basically, when it’s time to repair a relationship, it takes both sides admitting that they still have some rough edges. And that they care enough about the future of the lodge to keep chipping away. “Harmony isn’t a passive act,” Smith says. “It requires diligence. You have to try. Brotherly love is not a secret sauce. It takes work.”

But then, that’s the point of Masonry: to tackle the work together.

ILLUSTRATION BY

Raul Arias

Meet a San Francisco café owner giving back through Freemasonry.

At the Masonic Homes of California, a veterans memorial builds a bridge to the not-so-distant past.

A historic Masonic temple in Vallejo finds new life as artists’ lofts.