At the Masonic Homes, Staying Ahead of the Curve

With the coronavirus wreaking havoc across the state, the Masonic Homes of California sprung into action to ensure the health of its residents and staff members.

By Lindsey J. Smith

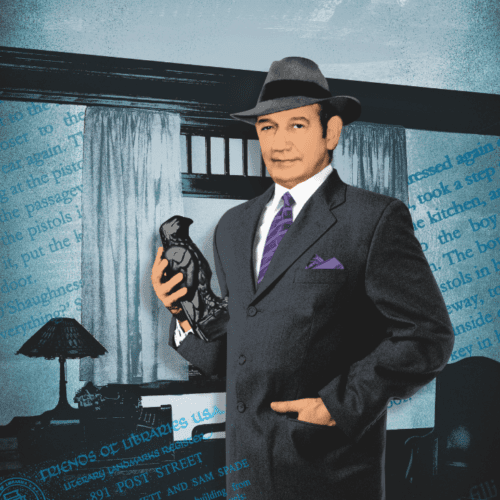

William Arney’s life took a turn the day he bought his gray fedora. It was November 1981; the purchase was in celebration of his big move to San Francisco, the cool gray city. Three months earlier, he’d arrived on a one-way ticket from Illinois with nothing more than his two suitcases and a job interview lined up.

Turns out the fedora was a savvy move; that winter was a wet one. Arney paired the hat with a gray trench coat, cutting such a striking figure around town that a friend suggested he start reading Dashiell Hammett’s hard-boiled detective novels. The tip resonated with Arney, who plunged himself into the classic San Francisco writer’s crime dramas, including The Continental Op, The Thin Man, and Red Harvest. Arney, now a member of Marin Lodge No. 191 and California No. 1, was hooked.

A year later, he signed up for a Hammett-themed walking tour of downtown San Francisco, visiting the real-life sites described in the novelist’s most famous stories. The tour stopped outside the unassuming building at 891 Post Street, where the writer lived from 1926 to 1929 and wrote his first three novels, including his most celebrated, The Maltese Falcon. He didn’t think much of it. But the memory of the building stayed with Arney for more than a decade, until one night in 1993 when he passed by the corner in a taxi and noticed a “For Rent” sign in the window.

Talk about foreshadowing. Arney, already something of a Hammett fanatic, was buzzing. But he needed to know if the available unit was actually the great writer’s. Hammett’s letters from the time bear the return address of 891 Post Street, but never listed a specific apartment number. So, like a gumshoe from the Continental Op detective agency, Arney started digging for clues. First he turned to his well-thumbed copy of The Maltese Falcon, in which the protagonist, detective Sam Spade, lives in an apartment widely believed to be modeled on Hammett’s own. Arney, an architect by trade, sketched a layout of Spade’s flat based on descriptions from the book, mostly in three key scenes. Then he compared those with a blueprint of the 1917 building.

The plans he found weren’t very detailed, but they did contain the original design of the bathroom. The Maltese Falcon ends with an iconic scene in which Spade searches the femme fatale, Brigid O’Shaughnessy, for a key piece of evidence in the bathroom of his apartment:

He sat on the side of the bathtub watching her and the open door. No sound came from the living-room… He put his pistols on the toilet-seat and, facing the door, went down on one knee… He did not find the thousand-dollar bill. When he had finished he stood up holding her clothes out in his hands to her. “Thanks,” he said. “Now I know.”

To Arney, that was crucial intel: The room was shaped such that Spade could sit on the edge of the tub, within reach of the toilet seat, and still leave enough room for O’Shaughnessy to stand between him and the door. “Just with those criteria, I was able to eliminate almost every apartment in the building,” he says.

Except one. Apartment 401, the very unit up for rent, in the building’s northwest corner, fit the bill. It had other telltale quirks, too, like a 90-degree bend in the hallway mentioned earlier in the novel. All told, the apartment was a miniscule 300 square feet. No matter. Arney moved in.

The closer he looked, the more Arney found clues about the apartment’s literary past. Weeks after signing the lease, Arney flaked a bit of paint from a doorjamb. Underneath was the flat’s original varnished wood detailing, which proved easy to strip. Arney began to meticulously restore the apartment to its original. He refinished the flooring, installed a vintage glass-and-wood door he found in the basement, purchased a Murphy bed, and furnished the unit with other circa-1920s pieces. He even created a secret compartment in the floor under the desk. “It would have been a great place for a gun—or an unfinished manuscript,” Arney says.

As the apartment got closer to resembling Hammett’s, Arney delighted in rereading The Maltese Falcon. “You can pretty much put yourself in the story,” Arney says. Watching headlights move across the wall at night, “I got the creepiest feeling, looking up at the ceiling and thinking, This has got to be just about exactly what Hammett saw every night when he went to bed,” he says.

Arney invited the Hammett walking tour to make the apartment a regular stop. Before long, he’d became part of the inner circle of Hammett fandom. He went to the unveiling of the Maltese falcon statuette from the 1941 John Huston and Humphrey Bogart film at John’s Grill, another locally famous Hammett haunt. He met Hammett’s daughter and granddaughter. And in 2005, when the group Friends of Libraries USA installed a plaque on the building to commemorate it as a literary landmark, Arney met and befriended Eddie Muller, the founder of the Film Noir Foundation, who asked Arney to serve as an announcer at the popular San Francisco Film Noir Festival.

For 16 years, Arney lived in apartment 401. But unlike the bachelor Sam Spade, 300 square feet didn’t cut it once Arney got married. Still, he kept the apartment for two more years after tying the knot, even following a move to San Rafael, fearing that if he gave it up, a new tenant would undo his hard work. Salvation came, as in so many mystery thrillers, from a shadowy stranger—in this case a “billionaire with a literary inclination.” Arney won’t name names, but the silent partner took over the lease and agreed to preserve the apartment.

Today the unit remains much as it was in 1929, unoccupied but cared for, as if awaiting Sam Spade’s return from dinner at John’s Grill. A tinny alarm clock and a copy of Drake’s Celebrated Criminal Cases of America—a Spade standby—rest on the desk. A leather rocking chair sits in a corner. At night, lights from cars streaming down Post and Hyde rake across the walls and ceiling, like roving eyes searching for clues.

PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION CREDIT:

JOHN RITTER

With the coronavirus wreaking havoc across the state, the Masonic Homes of California sprung into action to ensure the health of its residents and staff members.

Mystery writer James Lincoln Warren is an expert author of the hardboiled crime story.

Meet the Invisible Lodge, the most mysterious Masonic group in the known—or unknown—world.