At the Masonic Homes, Staying Ahead of the Curve

With the coronavirus wreaking havoc across the state, the Masonic Homes of California sprung into action to ensure the health of its residents and staff members.

By Ian A. Stewart

Masons share a fondness for unraveling life’s great mysteries. James Lincoln Warren loves putting them together.

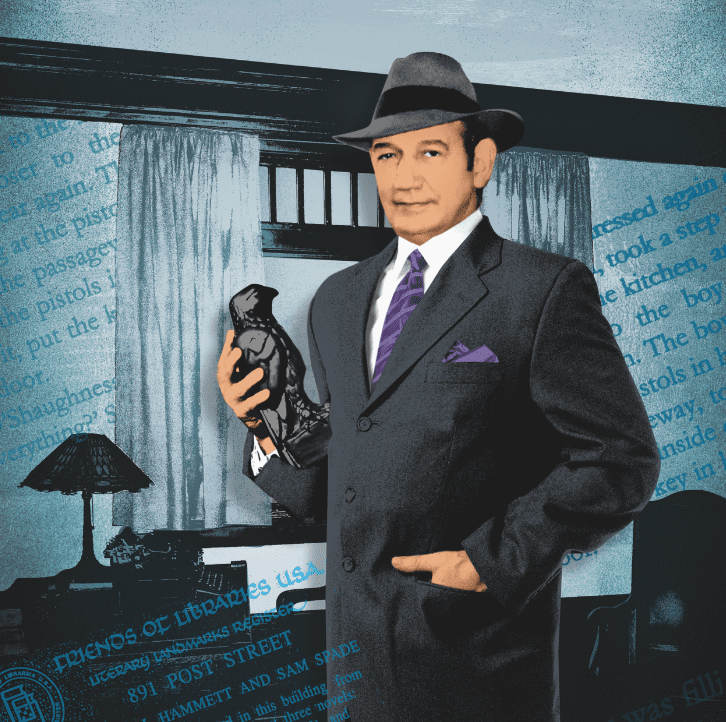

Warren, of Santa Monica-Palisades Lodge No. 307, is an expert of the tightly wound detective story. He is a frequent contributor to the long-running Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, and a past president of the Southern California chapter of the Mystery Writers of America. He’s behind two celebrated mystery series: the Treviscoe of Lloyd’s stories, about the exploits of an 18th-century insurance investigator; and the Cal Ops detective agency series, about a multiracial PI outfit probing contemporary Beverly Hills. A master of both his crafts, Warren was given the Black Orchid Novella Award in 2011 by the Nero Wolfe Society, and in 2019 he received the Hiram Award for service to his lodge.

California Freemason caught up with the prolific writer to talk about parallels between Masonry and mystery writing, and the enduring appeal of pulp fiction.

CALIFORNIA FREEMASON: How did you get started as a crime writer?

JAMES L. WARREN: I started writing in grade school. I had my first published story at 19, but it took me 20 more years to get another story published. At that time, I was writing mostly science fiction, but it wasn’t really cutting-edge. Science fiction is the literature of ideas; mystery is the literature of behavior. Temperamentally, mystery was a better fit for me.

CFM: You differentiate between hard-boiled crime fiction and noir. What’s the difference?

JLW: Hard-boiled is about tough guys who win. Noir is about tough guys who lose. So, for instance, The Maltese Falcon is hard-boiled, but Double Indemnity is noir. Generally, there’s very little humor in noir; it’s about desperation, some sort of obsession.

CFM: What are the essential elements of the genre?

JLW: Writing hard-boiled stories, as I do, you have three characteristics. First, rather than being a fair-play puzzle, like in Hercule Poirot, they’re usually travelogues. There’s a lot of shoe leather. You discover the clues as the detective does and you arrive at the solution at the same time as the detective. Then, you have a mix of convention and invention. The convention is the thing you expect to see to be satisfied—the knight in rusty armor, as someone called it. The detective with his own code of ethics. The invention is how you differentiate it—often through the use of setting. The setting is almost a character in itself.

CFM: Why do you prefer to work in short stories, rather than novels?

JLW: In terms of choosing it as a form, it’s a matter of temperament. I remember I was on a conference panel and the moderator, a novelist who was a friend of mine, introduced me by saying, “Jim does something I don’t do. I build clocks; he makes watches.” And I thought that was a perfect analogy of the novel versus the short story. Everything has to fit exactly with every other piece, all tightly packed.

CFM: Why do you think crime drama remains so popular as a genre in literature and film?

JLW: You know, I used to work in a bookstore, and if someone came in and said, “I don’t like mysteries,” I’d say, “I’m sure I can find a mystery you’ll like.” Mystery encompasses everything from madcap humor to serial killer stories. Most mystery readers are above average in intelligence, so that process of putting together the pieces of the jigsaw appeals to them.

CFM: Do you see any similarities between Freemasonry and crime fiction? Both deal with mysteries and secrets, of course.

JLW: The primary thing that connects Freemasonry to crime fiction is ethics and morality. In the final analysis, every crime fiction story winds up being a morality play— the difference between right and wrong. The symbols of Freemasonry almost uniformly have to do with becoming a better person. The three big metaphors of light, or knowledge; travel, as in the journey through life; and geometry, or the building of things—they all apply to crime fiction, too.

CFM: Have you ever made references to Masonry in your stories?

JLW: The first year I was a Master Mason, I was appointed chaplain of our lodge by Ara Maloyan and his senior warden, David Ferreria. Our secretary at the time could never pronounce their names correctly. He’d call them Malone and Ferrari. I thought, Ferrari and Malone—sounds like a buddy-cop movie. And from that errant thought came Custer Malone and Carmine Ferrari, the two principal detectives in the Cal Ops stories.

And while the multiracial makeup of the agency was categorically reflective of Masonic ideals, the stories themselves owe more to Rex Stout and the late San Francisco crime writer Joe Gores’s DKA Files stories. But the lodge enjoyed the gag.

PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION:

Clark Miller

With the coronavirus wreaking havoc across the state, the Masonic Homes of California sprung into action to ensure the health of its residents and staff members.

When a tiny apartment with a big-time literary past came up for rent, William Arney found himself walking in Sam Spade’s footsteps.

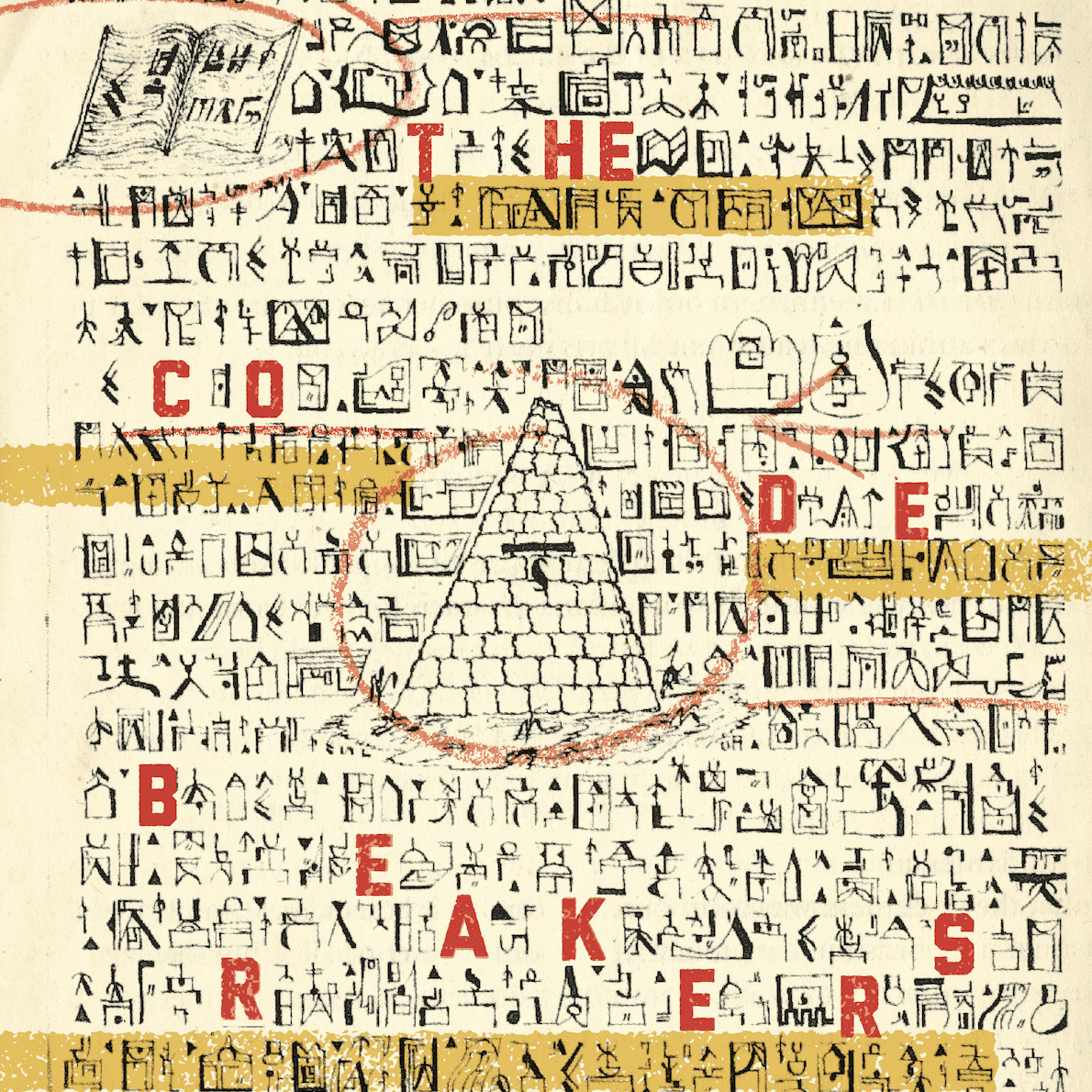

For more than 150 years, the Folger cipher had Masonic experts stumped—until Dr. Brent Morris and his team at the NSA took their turn.