Quarantine, Disease, and Masonic Relief—170 Years Ago

During the Sacramento Cholera Outbreak of 1850, Masons took the reins of a public health emergency.

By Lindsey J. Smith

On the morning of November 8, 2018, Bill Richards was up with the sun. Around 7 a.m., as he was feeding the chickens on his ranch home in Paradise, he saw smoke rising beyond his back fence. Like many towns throughout California, Paradise, in Butte County, was no stranger to fires—a series of blazes a decade prior had destroyed a few hundred homes in the area—and by this point, Richards, a past master of Table Mountain Lodge No. 124, knew the drill.

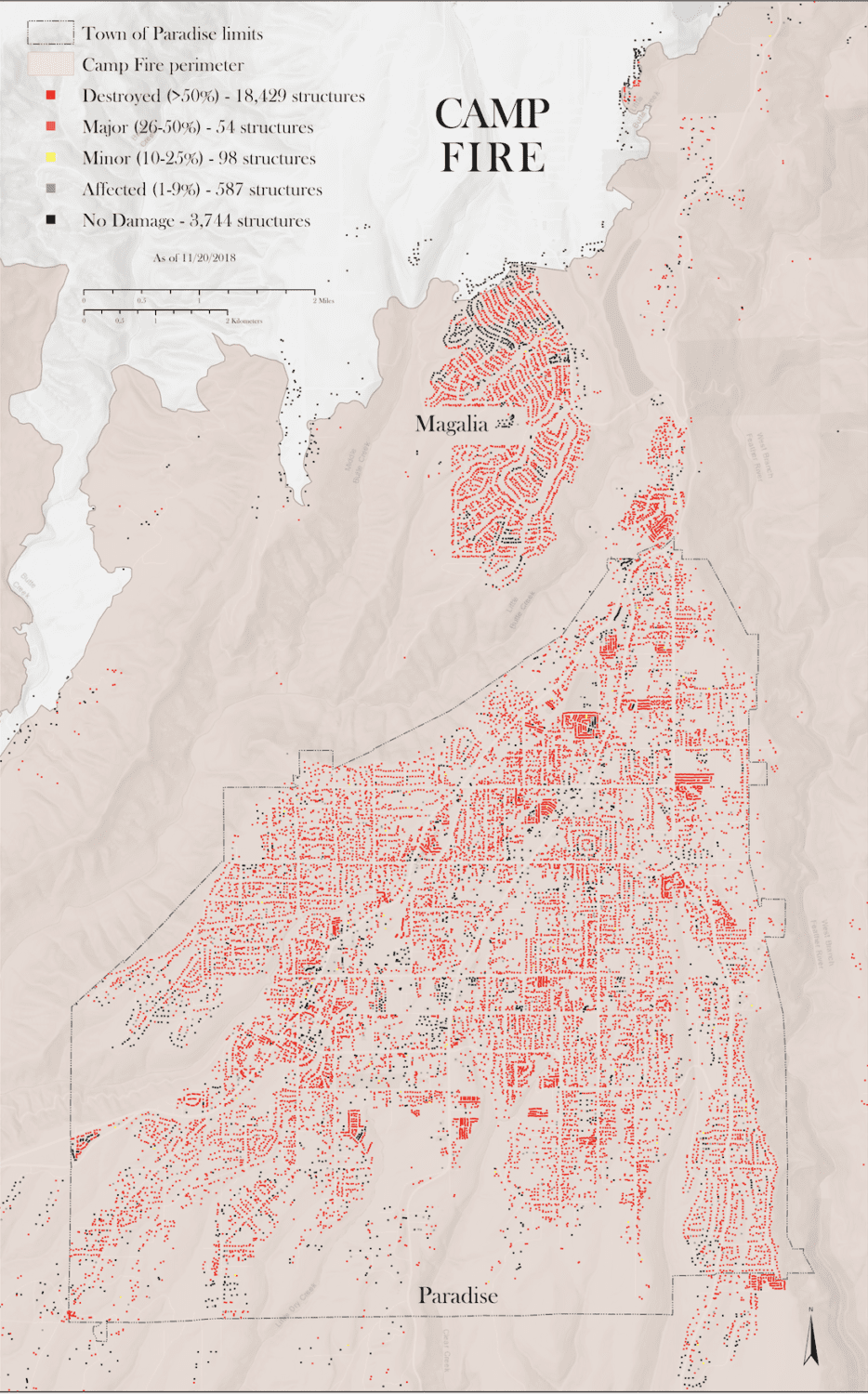

He called the fire department to report the smoke and was told that crews were on their way. Just to be on the safe side, he and his wife, Becky, drove down the block to scout the fire’s location. It was too close for comfort, so they returned home and began packing. “I managed to hook up my trailer and got the dog,” Richards remembers. “She got the car, and we grabbed a few clothes and our computers and got the heck out of there.” By the time they got the call to evacuate what was rapidly turning into the Camp Fire— which would go on to incinerate 153,000 acres, destroy 18,000 buildings, and claim 85 lives, making it the deadliest fire in California history—giant smoldering embers were already showering their front yard.

On his way out of town, Richards did what many Masons in an emergency do: He called a Mason. In this case, it was past lodge master Bill Spencer. Spencer lived in Paradise until 2008, when that year’s fires came within 150 yards of his home. Since then he’d moved to Chico. Still close friends, Richards and Spencer had plans to drive a group of children to the Shriner’s Hospital in Sacramento that week. So when Richards called to warn Spencer about the approaching fire, he said that the trip to the hospital would have to be canceled.

Spencer didn’t miss a beat: He invited Richards and his wife to come stay with him as long as they needed. Grateful, the Richardses headed east to Chico. By the time they reached the Paradise city limits, their house had burned to the ground.

While the coronavirus outbreak has spurred a nearly unprecedented outpouring of Masonic relief, the megafires that have become an almost yearly occurance in California have recently given Masons a chance to show their commitment to the cause. In each instance, lodge members have reached out to one another to offer help any way they can. From the Thomas Fire, which claimed 23 lives near Santa Barbara in 2017; to the 2017 Tubbs Fire in wine country that claimed 22 and the Camp, Carr, and Mendocino Complex fires that blazed through Northern California in 2018, Masons have lent a hand in ways big and small to help their brothers in an urgent time of need. “It gives you a little bit of grounding,” Richards says, choking up at the memory. With no home to return to and nothing but the few possessions they’d hastily packed, he and his wife ended up staying with Spencer for three months.

Examples like theirs demonstrate the unique position Masons are in to offer relief in the wake of a disaster. That happens both at the local level, where lodge members can check in on one another, and at the state and national levels, where resources can be activated and directed to those in urgent need. Psychically and institutionally, Masons are expected—and eager—to step in and help. “It’s part of our culture,” says Past Grand Master Bruce Galloway, whose home lodge, Reading-Trinity No. 27, had its own recent brushes with wildfire. “It’s our obligation to assist all distressed brother Masons.”

Richards recalls the state of shock he and so many others in Paradise experienced in the first few days of the Camp Fire. Nevertheless, the lodge kicked into gear. Members reached out over the phone, by text message, and on Facebook. Long email threads attested to members’ whereabouts and safety, particularly elderly members and widows. “Over the course of the week, we checked in about where everybody ended up,” says Brian Grandfield, the lodge secretary. Fortunately, no members’ lives were lost, but Grandfield estimates that 95 percent suffered material losses. As news of the disaster spread, donations and calls of support poured in from lodges near and far, with people offering spare bedrooms, connections to rentals, storage areas, meeting space, or just a sympathetic ear.

Those offers weren’t confined just to Paradise. Earlier in 2018, as the Carr Fire tore through Shasta and Trinity counties, members of lodges there sprang into action. Matt Larsen, then a junior warden at Western Star No. 2 in Shasta, recalls getting a call from Uriah McBroom, then master of Redding No. 254. “He asked, ‘What do you need? How can I help?’” Larsen says. Before long, McBroom had shown up with his trailer, and together he and Larsen emptied the Shasta lodge of its valuables. Their next stop was secretary Chris Wordlow’s home, a mile away, in the direct path of the blaze, to help him load up his own possessions. Ultimately, Wordlow was one of three lodge members who lost their homes. He wound up staying with past master Richard Montgomery for several weeks.

Instances like that of Masons helping Masons have played out across the state, attesting to the lodge’s status as an effective, if informal, support network. In the days after the Carr Fire broke out, Larsen says that he studied his lodge’s member directory, typing addresses into an online map to determine who lived in the fire zone, then directed them to service providers.

During the Thomas Fire and the subsequent mudslides in Santa Barbara County in 2017, which burned 281,000 acres and destroyed more than a thousand buildings, donations poured into local lodges. “We literally had supplies piled to the ceiling on all three floors of the lodge,” says Past Grand Master and King David’s No. 209 member Russ Charvonia. “It was overwhelming. We had people coming in all day long and walking out with bags of stuff to take to the fairgrounds or to friends.”

Masons provide relief at higher organizational levels, as well. Statewide, Masonic Outreach Services, run through the Masonic Homes of California, exists to offer those in need access to services and financial support, while the Grand Lodge office in San Francisco can direct fundraising dollars and coordinate recovery efforts. After the Camp Fire, Masons from around the state funneled donations to the California Masonic Foundation, which was able, through Masonic Outreach Services, to disperse much-needed funds to affected lodges.

Nationally, groups like the Masonic Service Association of North America have performed similar tasks: In 2018, following the Camp Fire, MSANA put out an appeal for relief to members across the country, leading to more than $200,000 in donations for affected Masons. It made similar nationwide appeals in 2004, in the wake of a series of wildfires around the state, and in 1993 and 1989, following the Northridge and Loma Prieta earthquakes, respectively.

After the Camp Fire, Richards, Spencer, and fellow lodge member Charlie Haggerty were tasked with distributing donated funds to members of Table Mountain Lodge. They designed a survey to assess people’s losses and insurance coverage, which helped them split the money equitably. “Masons are altruistic,” Richards says. “And they don’t like asking for help.”

For members who’d lost everything, often the seemingly smallest forms of relief were the most meaningful. Richards recalls members of Nevada No. 13 donating a trailer packed with supplies to the lodge. Elderly residents and staff at the Masonic Homes loaded trucks with goods. Masonic-affiliated groups like the Seekers of Light motorcycle association organized group rides to deliver materials. And countless lodges offered to help replace the aprons, bibles, and other Masonic paraphernalia lost in the fire.

Providing aid to those in need is a core tenet of Masonry—and one that California Masons have, historically, been all too familiar with. And it isn’t only wildfire. In the state’s early days, building fires were practically ubiquitous. In the most famous example of Masonic fire relief, Masons in 1871 banded together after the Great Chicago Fire to donate more than $100,000 to the city—so much that the Grand Lodge of Illinois sent refunds to many states, including $1,874 to California. Thirty-five years later, that favor was repaid after the 1906 earthquake and fire leveled San Francisco and destroyed its Masonic Temple. Almost overnight, more than $315,000—upwards of $9 million in today’s dollars—was raised by Masonic jurisdictions across the country for San Francisco, and hundreds of Masons spent weeks providing direct relief in the broken city.

As the Camp Fire raged and members feared for the fate of their homes, Table Mountain Lodge also hung in the balance. About a week into the fire, word broke that the lodge had been saved by an unknown Good Samaritan. As Spencer heard it, “Somebody hollered at the strike team during the fire, ‘Whatever you do, save the lodge.’” One group of firefighters stayed behind and made sure the lodge survived. “They were the ones that gave us the framework to recover,” Spencer says. “And for that I’m very grateful.”

For Richards, the lodge’s survival was a beacon in an otherwise dark time. Not only did he lose his house—it’d been recently remodeled but not reinsured to its new value—he also lost the tools for his woodworking business, including some he’d inherited from his grandfather.

Although the lodge hall survived, it would be a long time before it was usable again. In December 2018, members gathered at Chico-Leland Stanford No. 111 for their first meeting back. It was emotional. “The damage from the fire goes well beyond having all your stuff burned,” Richards says. “The loss of community is the thing most people are feeling.”

The challenges to the lodge were immediately clear: Members had scattered to the wind, some temporarily, others permanently. “When 50 percent of your membership goes away overnight, how do you keep going?” Grandfield asks. Members determined that, no matter what, they wouldn’t consolidate. “Table Mountain Lodge is not going to fold because of a fire,” Grandfield says. “We’re going to keep it going, stay strong together.”

Carrying on came with changes. For the next year, the lodge met in Chico, which itself had only narrowly escaped disaster. They moved meetings from Monday night to Saturday afternoons so more members could participate. Some who hadn’t been active for years stepped into leadership roles. Others forced to move away continued paying dues, recognizing how important the connections formed in lodge remained. That display of brotherhood had an effect on those who witnessed it. “It’s just now sinking in,” says Brad Marr, lodge master of Chico-Leland Stanford No. 111. “At the time, it was just chaos. There wasn’t even a thought about helping—it’s just what you do. But now, as we go to other lodges for degrees, we run into people from Paradise, and they tell us how much it meant to them to be able to keep on meeting.”

Marr is still moved by the generosity he saw in the wake of the fire. At one point, the offers of assistance were so overwhelming that he instructed lodge secretary Sidney Crane to make a spreadsheet so members could connect with would-be donors. One Mason offered to fly a National Guard helicopter full of supplies to them. All around him, Marr says, he felt the Masonic spirit of relief permeating the community. “The whole town, everyone was giving. I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s like everyone was a Mason.”

Eventually, lodge members turned their attention to their own building. Spencer, who had spearheaded a solar project at the lodge before the fire, offered to lead the circa-1936 hall’s rehabilitation. He coordinated between Grand Lodge and the insurance company, wrangled permits, communicated with contractors, and supervised cleanup of water damage. Knowing there wasn’t much he could do to help the lodge recover its membership, he focused on rebuilding.

Table Mountain No. 124 reopened in September 2019, after months of delays caused by testing of the municipal water system. The first meeting back was a celebratory affair, and a degree ceremony followed in December, with sideliners joining in from as far away as Sacramento. “A lot of people came up, people who didn’t know our candidate,” says Harwood “Woody” Nelson, the current lodge master. “I guess that’s part of Masonic history: We’re here to help one another.”

Bill Richards, who at the time of the fire was the district inspector for Paradise, Gridley, Oroville, and Forbestown, has yet to return. The loss pushed him and his wife to bump up their retirement plans. They bought a mobile home and have been driving across the country, visiting friends and family— and, of course, other lodges. “I receive a great reception everywhere I go,” he says. He still pays dues at Table Mountain No. 124 and plans to come home for its rededication, which had been scheduled for July. (A new date has not yet been set.)

The brothers of Table Mountain don’t want to let the Camp Fire define them, but know that it has undeniably changed them. “I think we’re more together now,” Nelson reflects. “We still have our own lives, but part of that individual life is the lodge and the community.” Just as they were hosted in Chico, they’re trying to be a home away from home for other local organizations in need. “We want to make sure that the community itself is helped out by our lodge,” Nelson says. “We know we were very, very fortunate.”

FOR CALIFORNIA’S earliest Masonic lodges, fire was a constant. By one account, more than a fifth of the state’s first 200 lodges were lost to fire. By 1906, when the great earthquake and fire in San Francisco leveled the Masonic Temple, California Masons were already well acquainted with having to rebuild. Here, a partial timeline of Masonic baptisms by fire. —IAS

1849

Pacific Lodge UD (chartered through the Grand Lodge of Illinois) burned.

1851

Sutter Lodge No. 6 (Sacramento) burned.

Nevada No. 13 (Nevada City) burned.

1852

Tuolumne No. 8 (Sonora) roof burned; hall destroyed shortly thereafter.

Georgetown No. 25 (El Dorado County) burned.

1853

Western Star No. 2 (Benton City) burned.

1854

The lodge room of Washington No. 20 (Sacramento) burned.

1855

Mokelumne No. 31 (Calaveras County) burned.

Madison No. 23 (Grass Valley) burned, along with the whole town.

Bear Mountain No. 76 (Angels Camp) burned.

1856

Entire town of Placerville, including El Dorado No. 26, burned.

Nevada No. 13 again burned.

St. James No. 54 (Tuolumne County) burned.

Mormon Island (Sacramento County) burned, including Natoma No. 64.

1857

St. Louis No. 86 (Sierra County) burned.

Late 1857 or early 1858, Quartzburg No. 98 (now Hornitos) burned.

Exact date unknown, but Indian Diggings No. 85 (El Dorado County) burned; shortly after, lodge surrendered charter.

1858

Mariposa No. 24 (Mariposa County) burned.

Entire town of Michigan City (Placer County), including Michigan City No. 47, burned.

1859

Windsor No. 116 (Sierra County) burned.

Vallecito No. 118 (Calaveras County) burned; lodge surrendered its charter.

St. James No. 54 again burned.

1860

Entire town of Amador burned; Amador No. 65 lost records but hall survived.

1861

Oro Fino No. 137 (Siskiyou County) burned and surrendered its charter.

Don Pedro’s Bar (Tuolumne County), including Mountain No. 82, burned.

Jefferson No. 97 (Plumas County) burned.

1862

Forbestown No. 50 (Butte County) burned.

Amador No. 65 again burned, but hall survives.

1863

Rising Sun No. 153 (Sierra County) burned and surrendered its charter.

Nevada No. 13 again burned.

1866

Again, Mariposa No. 24 burned.

1869

Quitman No. 88 (Tuolumne County) burned.

~1870

Sierra Valley No. 184 burned.

1871

Again, Natoma No. 64 burned.

Again, Tuolumne No. 8 burned.

1877

Vacaville No. 134 burned.

1879

Again, Mokelumne No. 31 burned.

1880

Landmark No. 253 (Madison, Yolo County) burned.

1882

Vesper No. 84 (Red Bluff, Tehama County) burned.

1883

Entire town of Dixon (Solano County), including Silveyville No. 201, burned.

Forest No. 66 (Sierra County) burned.

1884

Mountain Shade No. 18 (Sierra County) burned.

1888

Suisun No. 55 (Solano County) burned.

Lodge hall of Southern California No. 278 and Pentalpha No. 202 (Los Angeles) burned.

1895

Roseville No. 222 burned, but hall survives.

1898

Hope No. 234 (Beckwourth, Plumas County) burned.

1903

Fisher Hall, home of Palestine No. 351 (Los Angeles), burned.

1904

Truckee No. 200 burned.

Again, Forest No. 66 burned.

1905

Snow Mountain No. 271 (Stonyford, Colusa County) burned.

EACH YEAR IN OCTOBER, the names of the country’s firefighters and emergency medical service workers who died in the line of duty are added to the National Fallen Firefighters Memorial in a ceremony in Emmetsburg, Maryland. The event is a sober and meaningful one for the many colleagues and families that make the trip to pay tribute. The next time it occurs, they’ll be joined by another group of firefighting brothers: the members of St. Florian 9-11 Lodge No. 238, the only Masonic firemen’s lodge in the United States.

EACH YEAR IN OCTOBER, the names of the country’s firefighters and emergency medical service workers who died in the line of duty are added to the National Fallen Firefighters Memorial in a ceremony in Emmetsburg, Maryland. The event is a sober and meaningful one for the many colleagues and families that make the trip to pay tribute. The next time it occurs, they’ll be joined by another group of firefighting brothers: the members of St. Florian 9-11 Lodge No. 238, the only Masonic firemen’s lodge in the United States.

The lodge, chartered in 2015 by the Grand Lodge of Maryland, is open to all Masonic fire and EMS workers in that state and, through a new associate-member program, to personnel across the country. For a $25 initiation fee, the Hook Program offers associate membership along with a lapel pin, a bumper sticker, and access to all lodge events and communications. “The more I’m around these guys, the more similarities I see between firefighters and Masons,” says lodge master Ron Block. “We don’t all run into burning buildings, but it’s the same desire to do good for your community with good people. It’s definitely a brotherhood.” —IAS

PHOTO CREDIT:

Peter Hansen/CSU-Chico

Noah Berger/AP/Shutterstock

Harwood Nelson

Russ Charvonia

The Henry W. Coil Library And Museum Of Freemasory

Matt Larsen

Masonic Homes of California

During the Sacramento Cholera Outbreak of 1850, Masons took the reins of a public health emergency.

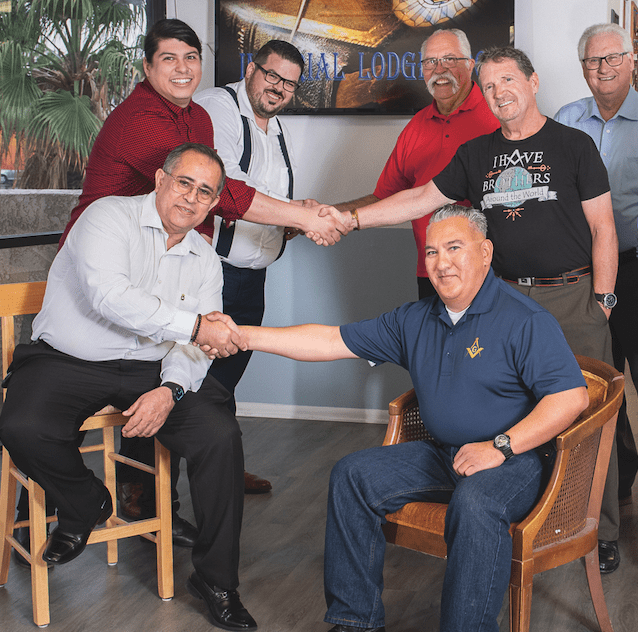

At Imperial Valley Lodge No. 390, Masons are making valuable community connections on both sides of the border; and tracking Masonic first pitch misfires in anticipation of another Masons4Mitts season.