A Second Home

For decades, Masonry has played a central role in the Filipino immigrant experience. Now a new generation is making its mark on the fraternity.

“You’ve almost got to experience it yourself to understand the immersion of Freemasonry in Filipino culture,” begins Felix Pintado. He knows of what he speaks. Pintado, who was born in the Philippines, is today the grand chaplain of the Grand Lodge of Victoria, in Australia, and served from 2014 to 2020 as Philippine consul to Melbourne. In 2018, he coauthored a deeply reported history of Freemasonry in the Philippines that was published by Quator Coronati, the leading Masonic lodge of research. We caught up with Pintado to discuss the unique melding of Filipino culture with Freemasonry and its role in society today.

CFM: Freemasonry is inextricably linked to the fight for Philippine independence. Why does that connection endure?

Felix Pintado: You can’t understand Freemasonry in the Philippines unless you understand Philippine history. Remember, there was 333 years of Spanish colonialism, and then 50 years of American rule before Filipinos could claim their own identity. And all of the independence figures were Freemasons. One theory is that in countries that have been brought up in a colonial, theocratical environment like the Philippines, people looked for something more secular that they could hang their philosophical hat on. People were looking for something that was secular, and that spoke of freedom. And so Freemasonry flourished.

CFM: But it’s a complex history, right? If José Rizal came back to life today, he would not be allowed to sit in most lodges since he belonged to a different grand lodge.

FP: It’s true that those Freemasons whose statues appear outside the Grand Lodge of the Philippines would not be admitted in any of their lodges today. But really, people today would say it’s a product of history. And I don’t know how many Filipino Masons know about all the various schisms and separatist movements. There’s an element of, Does it matter? They fought for our freedom, they gave their lives for this country, and they were Masons.

CFM: Something that Masons who visit the Philippines invariably mention is how much respect they’re afforded there. Is that just a really extreme version of Filipino hospitality or is there an element of elitism at play?

FP: There’s definitely a different way of doing Freemasonry. In some cases, it costs six months’ salary to become an entered apprentice. So you’re saving for many years to become a Mason. So yes, it can be elitist, and to be a master of a lodge, that’s a very big thing. But I think it comes from a time when being a Freemason could cost you your life. And one of the ways to keep it safe was to make it very difficult to become a Freemason. During the revolution, through groups like the Katiputan, which was quasi-Masonic, there was a real discipline about keeping things secret and exclusive. So, in many ways, it’s been hard to let go of a past that said, This is exclusive. And then the other thing is that following martial law in the 1970s, the Philippines lost a lot of the middle class. In recent years, they’ve had to cope with that, but it’s happening gradually.

CFM: In California, fraternal organizations like the Masons have played a crucial role for many Filipino immigrants in establishing roots. Is that the case in Australia as well?

FP: Yes, it’s about preserving and continuing the Filipino identity and traditions in an adopted country. And Freemasonry affords that very easily. Here in the Grand Lodge of Victoria, in 2019 we granted a dispensation for a new lodge called Plaridel Lodge to work the Philippine ritual—which is the California ritual—in our jurisdiction. That was unique, and it enabled a large Filipino group to join. We had 80 petitioners—that’s bigger than most lodges in existence here. It’s going very strong.

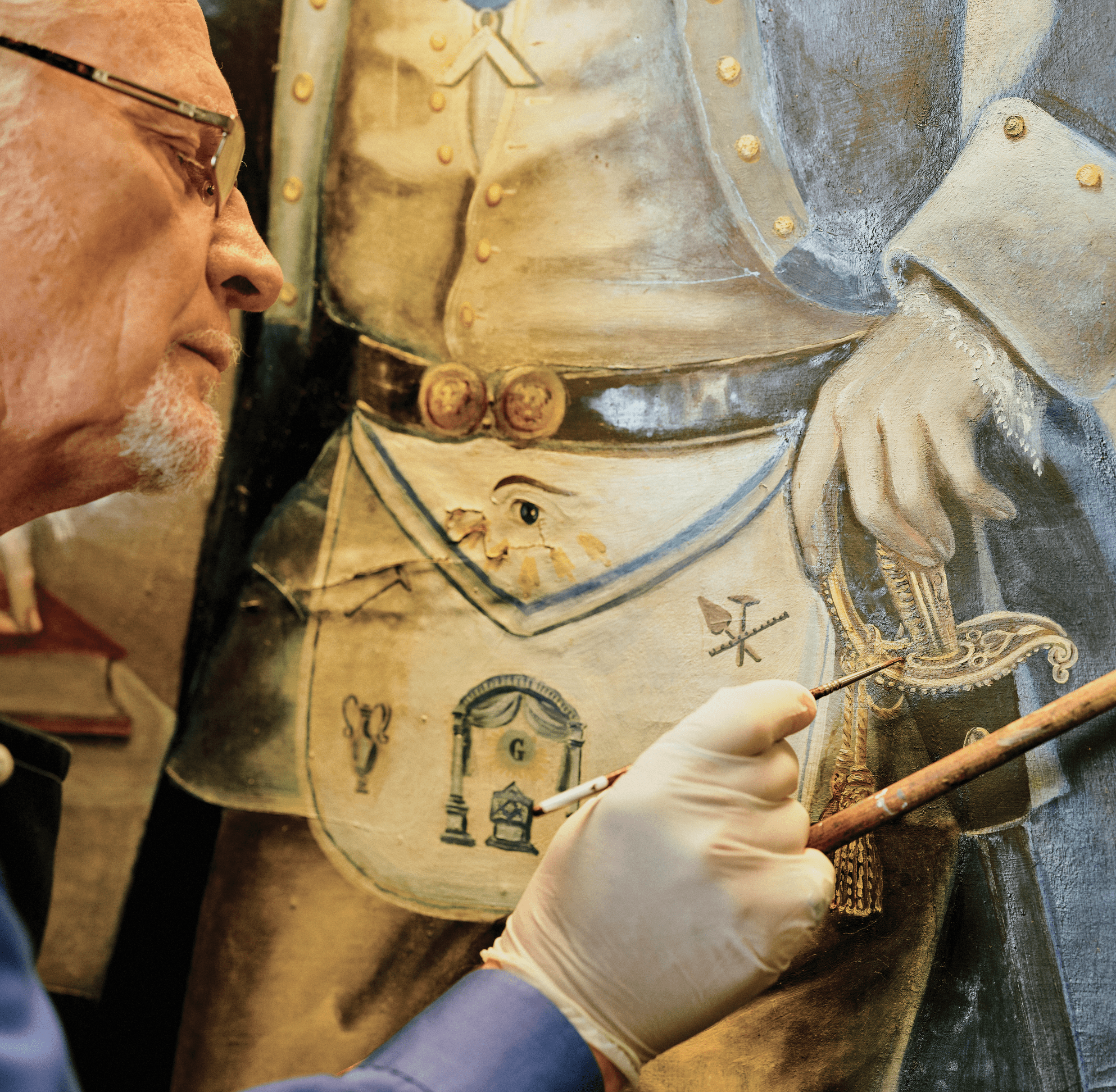

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Matthew Scott

For decades, Masonry has played a central role in the Filipino immigrant experience. Now a new generation is making its mark on the fraternity.