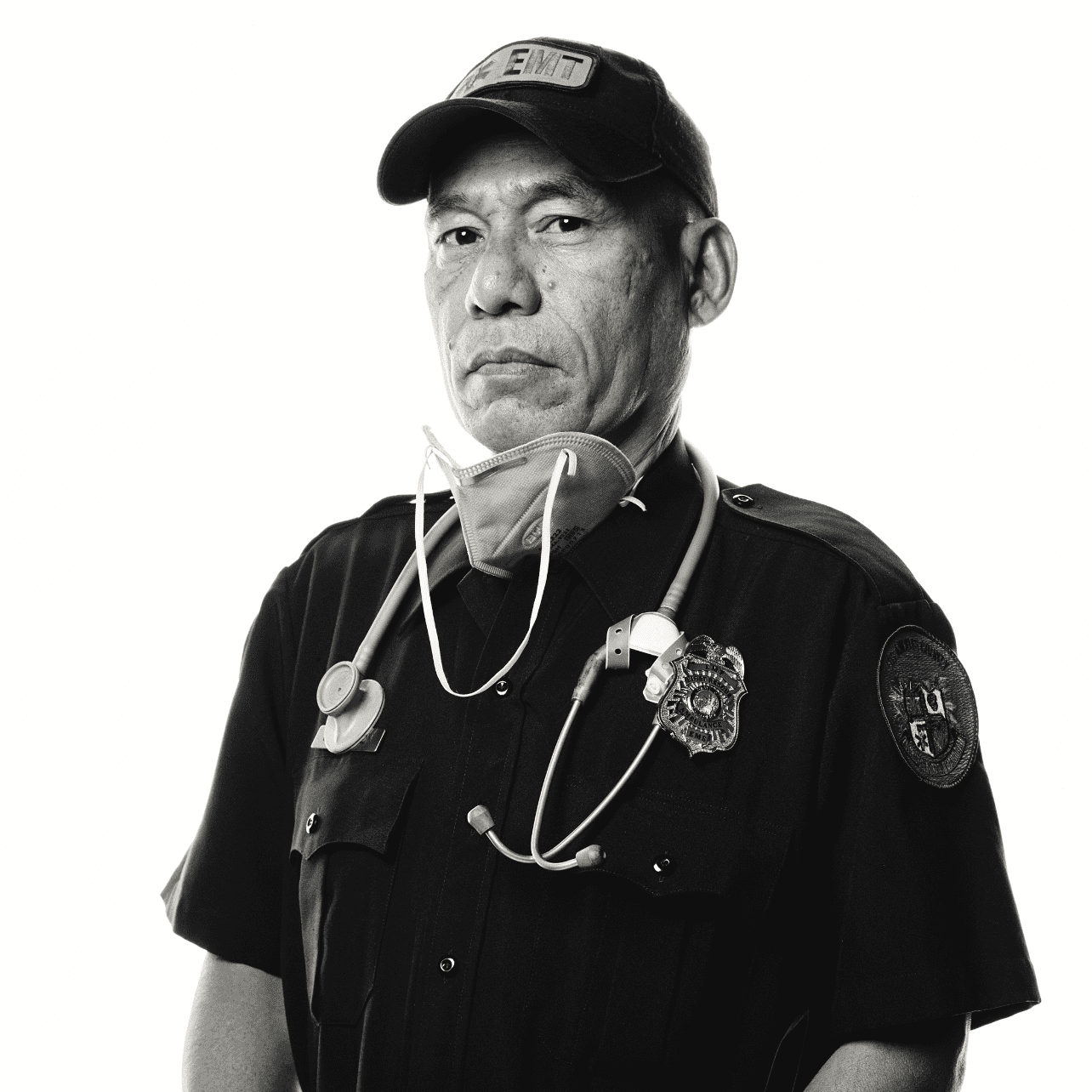

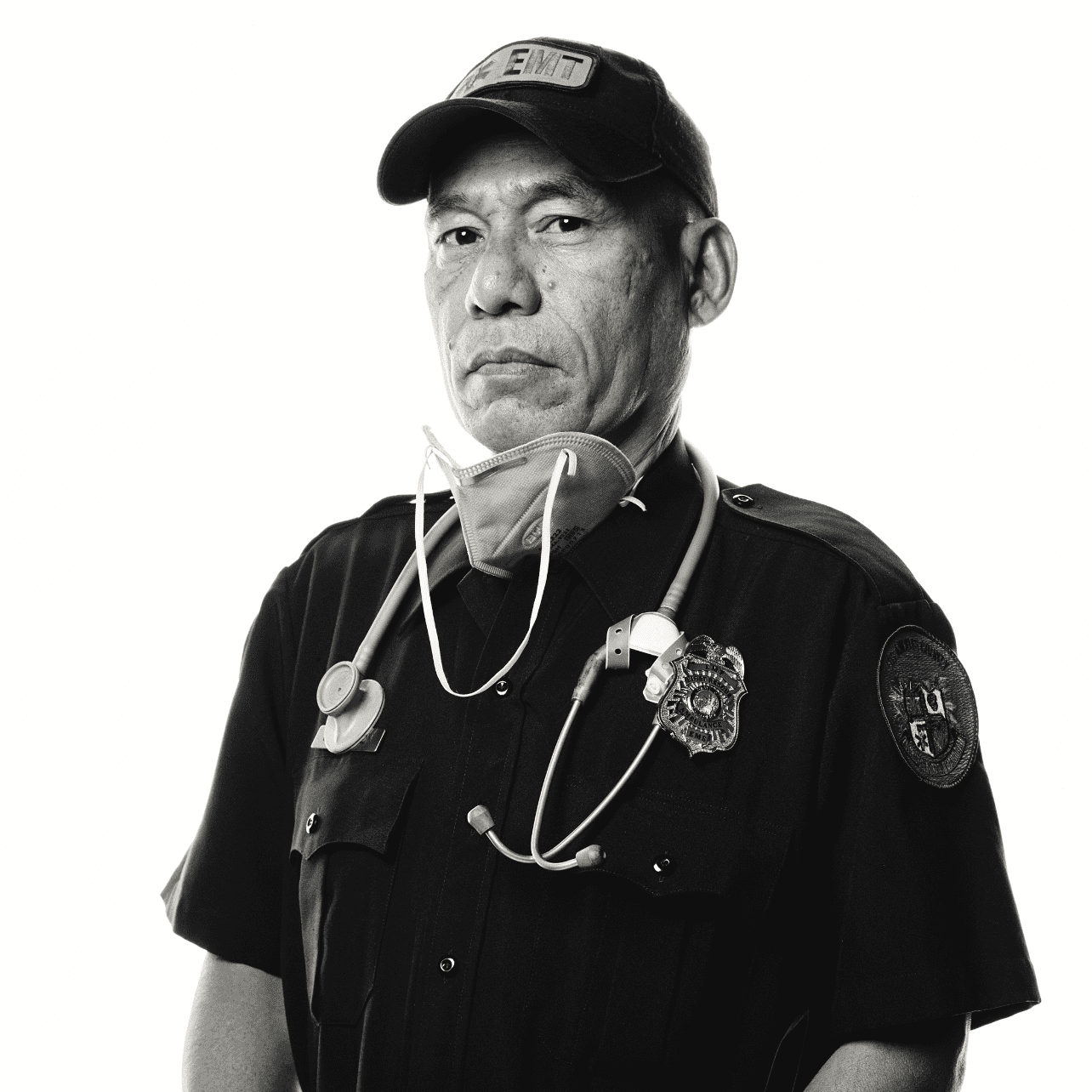

Three Masons Working as Death’s Doormen

Meet three Masons with an intimate familiarity with death—and the other side.

Hollywood has always had a flair for the dramatic. And in 1931, the town’s newest Masonic lodge was no exception. Abutting the massive Paramount Studios movie lot, the lodge played host to a theatrical midnight funeral service, billed in the press as an ultra-rare ceremony witnessed only a handful of times in history.

The Masons entered the upstairs lodge room for the service at the “low 12” hour, each holding a single candle. As they filed in, they flanked the coffin of the deceased, and a ritual prayer was read. Upon recitation of the last incantations, the Masons knelt and blew out their candles, and the room went dark. Silently, the pallbearers spirited the coffin through a secret door. When the lights came back up, the body had vanished.

Nearly a century later, the Masons are long gone, but the old lodge room still retains its magical allure. Situated within the old Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery, the two-story building on Santa Monica Boulevard now hosts some of Tinseltown’s most celebrated performers. In 2008, the site was rebranded as the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, with the Masonic Lodge acting as a venue for intimate concerts from renowned artists including Philip Glass, Moby, Karen O, and the National, among any others.

In short order, the Masonic Lodge has become a part of the fabric of Los Angeles’ cultural life. In addition to the concert series, it hosts Cinespia’s outdoor movie nights, which are projected against the exterior walls of the Churrigueresque lodge hall. Patrons sit under blankets beside headstones for some of the country’s most famous performers and celebrities, from Rudolph Valentino to Judy Garland to Chris Cornell.

All that gives the site one-of-a-kind ambiance. Jay Boileau, who has been Hollywood Forever’s executive vice president and director of cultural events since it was purchased out of bankruptcy in 1997, says the Masonic lodge there is no typical venue. “The way the room is designed with those high beams, it feels huge. But it’s actually a small room, so it feels intimate, too,” he says. “As you walk in, the wheels are turning in your brain.”

The history of the lodge is still apparent in its renovated state. Onstage, the lodge officers’ chairs are conspicuous reminders of its past. In 2009, rocker St. Vincent played one of the venue’s first-ever shows flanked by two of the ornate seats, with the Eastern Star light and intricate chandeliers suspended above her. Stained-glass windows full of Masonic emblems lent the room—and performance—a sanctified air.

When Boileau and his colleagues assumed control of the property, the lodge room had sat vacant for nearly 30 years and was being used mainly as a storage facility. It took them a year to clean out the countless cemetery documents, purchase records, and building models. At first they envisioned the space as a production studio for multimedia tributes of the deceased, but looking over the architectural models, an idea for a new use became clear.

Originally, the lodge’s presence was the work of one man. Frank Heron was a 32nd-degree member of the Scottish Rite, past commander of the Knights Templar’s Los Angeles chapter, and, beginning in 1922, president of the Hollywood Cemetery Association. It was Heron who helped turn the property into a modern memorial park and first made plans for a Masonic hall on its grounds.

In 1924, the Bankers Masonic Club of Los Angeles petitioned for a dispensation to form a new lodge. The following year, it was constituted as Southland № 618, with William Frederic Gallin as its first master and Heron as junior warden. At the time, Heron was exploring ways to build on the cemetery property, but city codes required any new construction on coveted Santa Monica Boulevard to be commercial.

Additionally, “He was under pressure to lease the space to an organization that was deemed appropriate to a cemetery,” says Heather Goers, an architectural historian who has been compiling a cultural landscape report on the cemetery while it’s under consideration to be named an L.A. historical monument. “People who had purchased lots in the cemetery didn’t want, say, a bar on the property. So his idea was to lease the upstairs space in this commercial building project to Masonic lodges.”

Above:

An exterior shot of the lodge hall at the former Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery. Courtesy of Hollywood Forever.

It was a perfect match, and Heron got the structure built almost immediately. Southland № 618 moved into the lodge room, which it shared for a time with Mt. Olive № 506, a group made up of movie studio men (including the producer Darryl F. Zanuck of The King and I). Heron served as the building manager until 1939, when Jules Roth took over. Roth managed the space until its sale in the 1990s. Southland № 618 decamped in 1967, and in 1979 consolidated into Southland Heritage № 618. In 1990, it consolidated again into the current Magnolia Park № 618.

And while the Masonic connection exists today in name only, the lodge’s history lends the site an atmosphere that’s hard to replicate. Says Boileau, “It really opens people up emotionally for an incredible artistic experience in a way other venues can’t.”

Above:

The original Eastern Star room inside the Masonic Lodge at what is now called the Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Courtesy of Hollywood Forever.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Courtesy of Hollywood Forever

Meet three Masons with an intimate familiarity with death—and the other side.

In San Diego, get to know a diversity-focused lodge where membership is an international Masonic melting pot.

The 18th century Benicia Masonic Hall, the oldest Masonic lodge in California, gets a 21st century makeover.