How Masonic Relief Boards Provided Support for 100 Years

For more than a century, California Masons supported one another—and brothers from around the world—through a vast network of boards of relief.

By Ian A. Stewart

Tucked near the bottom of the famous gossip columnist Herb Caen’s September 21, 1961, report in the San Francisco Chronicle was a brief adieu to what at one time had been the center of the Masonic social scene: “The old Fraternity Club… where once we danced with devilish grace, is not only gone for good, its fixtures will be auctioned off next week,” he wrote. “Now dry your martinis and try to carry on.”

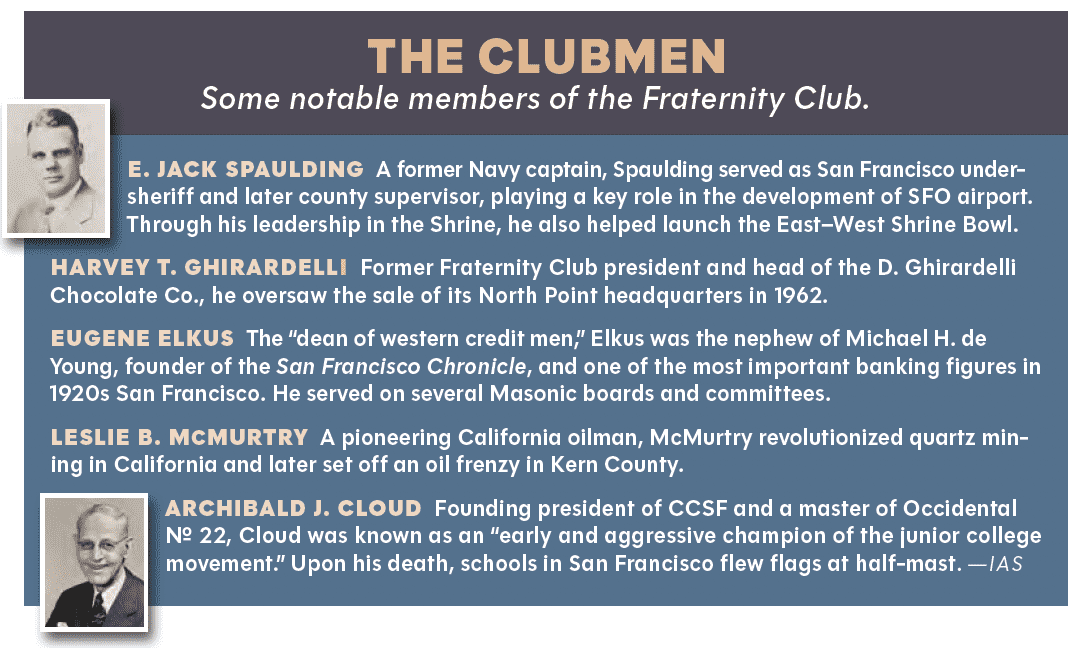

It was an ignoble end to what for almost half a century had been one of the most important—and lavish—centers of fraternal life on the West Coast. The Fraternity Club, originally called the Masonic Club, operated from 1916 until 1961 from suitably gilded digs at the Palace Hotel, and later at a Financial District clubhouse, providing its roster of nearly 2,000 members with a home away from home—and also away from lodge. There, the club brought together Masons primarily from the Bay Area, but also from farther afield, to hear speakers on current events, to socialize and network, and to wine and dine. In many ways the club, which included a who’s who of San Francisco movers and shakers (including, among its charter members, the banking magnate William H. Crocker; William P. Filmer, sovereign grand inspector of the Scottish Rite and first president of the Golden Gate Bridge District; and San Francisco postmaster Harry L. Todd), was the embodiment of the proverbial smoke-filled back room.

And yet its primary aims were altruistic. In 1917, the club funded and organized the Masonic Ambulance Corps, a team of nearly 100 California Masons who enlisted as the 316th Sanitary Train of the 91st Division during World War I. The corps served during the Meuse–Argonne Offensive, the deadliest campaign in the war, and earned a battle star at the Lys. The following year, Masonic Club members raised more than $452,000—that’s more than $10.3 million in today’s dollars—for the Third Liberty Loan war fund. During peacetime, the club organized Christmas toy drives and hosted orphans’ nights, providing children of all backgrounds with gifts, costumes, dinner, and entertainment.

On that front, the group was explicit about being more than just an old boys’ club. “The Masonic Club will be not only a social club composed of Masons— it will be a Masonic Club in the truest sense of the term, and conducted in accordance with the well-defined principles of the Order,” read an article in Masonic Trestleboard magazine.

One of its chief architects was John L. McNab, onetime federal attorney for the Northern District of California and a prominent lawyer at the time. (As attorney for the Chinese Six Companies, he was credited with helping establish peace among the rival tongs in San Francisco’s Chinatown.) During the Panama–Pacific International Exposition of 1915, he and other members of Bethlehem № 453 began formulating plans for a clubhouse full of amenities and comforts that members from around the country could enjoy while in town.

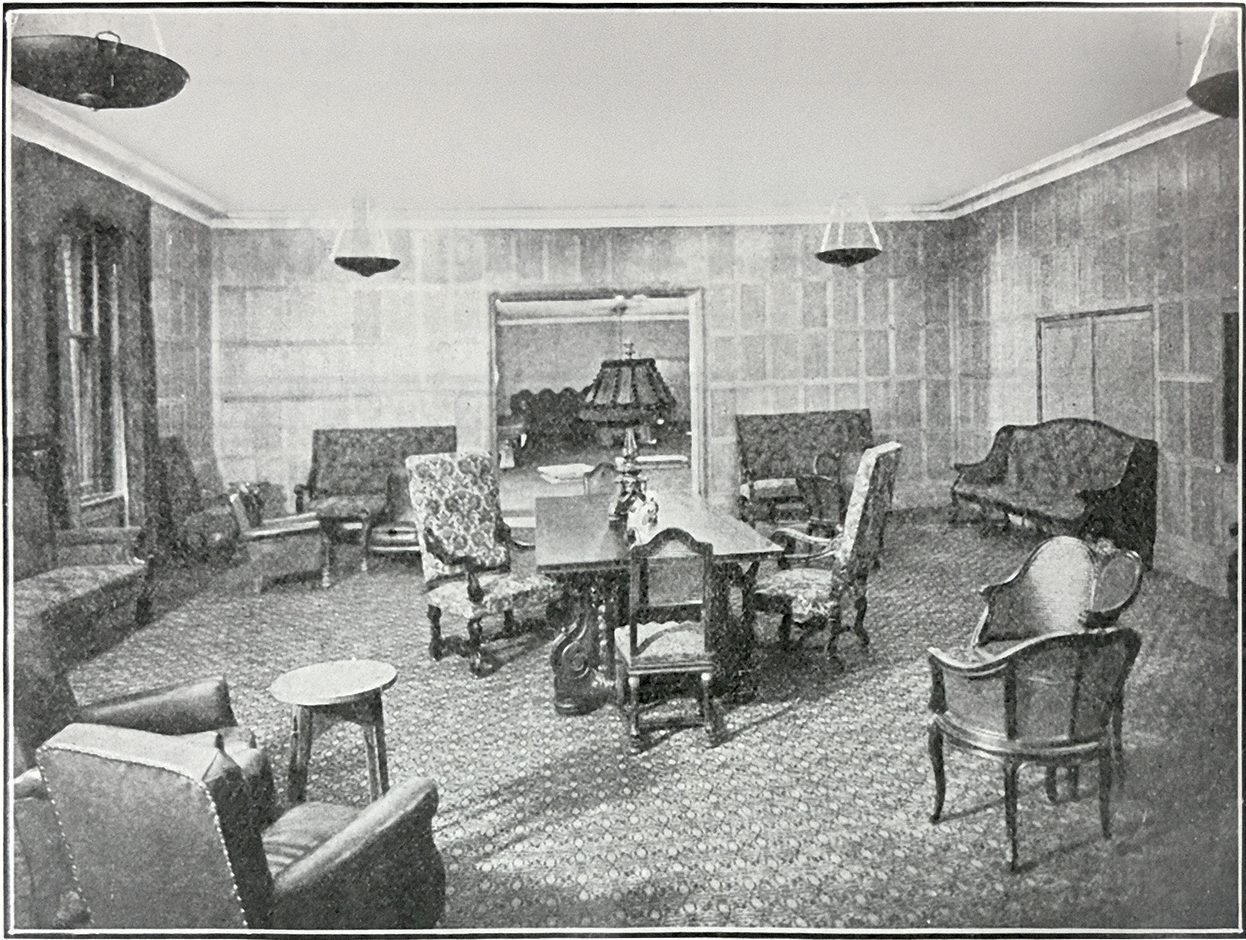

The idea proved popular. By December 1916, just a month after plans for the group were announced, the club had enrolled more than 2,000 charter members and begun construction of its $40,000 clubhouse, which would take up the entire western wing of the second floor of the famous Palace Hotel. To make room, the hotel renovated more than 30 rooms, including the Presidential Suite, where Ulysses S. Grant, William McKinley, William Taft, and Theodore Roosevelt had all stayed. The new clubhouse, which opened in December 1917, included a lounge area, a billiard room, a card room, a library and reading room, offices, and a dining room. “Beyond question, the appointments of the Masonic Club are of the very finest, and of such a character as to excite unstinted admiration,” read one review.

Unlike similar Masonic clubs in Detroit and New York, which were reserved for members of a specific lodge, the San Francisco outpost was open to all Masons. And indeed, among an initial 250 associate members were Masons from as far away as China, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Alaska.

Between WWI and WWII, the Masonic Club provided entertainment and recreation for a roster of about 900 members. That included bridge and billiard tournaments, ladies’ nights, and all manner of receptions—including an annual “high jinks” party featuring musicians, dancers, and other performers. In one 1921 advertisement, organizers touted a “strong man who promises to let any man in the audience stand on his chest while he lies on his back on a bed of sharp-pointed spikes.” Lectures were held at the club on subjects as varied as U.S.–Asian political relations, the “Ethical Practice of Law,” and, in spring 1941, the outlook for the upcoming San Francisco Seals baseball season.

During that time, however, the club began instituting changes. In the 1930s, the group was renamed the Fraternity Club, and its membership was extended to anyone recommended by a current member. In 1944, the club moved to a new headquarters at 345 Bush Street, where it had a large dining room, cafeteria, cocktail bar, library, card room, billiard room, and auditorium.

At the same time, the era of the men’s club was drawing to a close. By the 1950s, membership had fallen to a few hundred, and in 1961 the club finally sold the building and folded up shop.

Today, traces of the Fraternity Club are all but gone. And though it is little remembered even within California Masonry, its history is a reminder of a forgotten age of Masonic influence in the city. As one advertisement noted, in announcing the sale of the clubhouse’s stock and furnishings, “This club was furnished in excellent taste.” It was a fitting eulogy.

Illustration by RITTERlens

Photography:

Courtesy of the Henry W. Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

For more than a century, California Masons supported one another—and brothers from around the world—through a vast network of boards of relief.

East San Diego № 561 has made service to others paramount. For that, it is the 2025 Joe Jackson Award Recipient.

The International Conference explores Masonry in film, politics, and propaganda.