Serving Those Serve at San Dimas Lodge

In the San Gabriel Valley, San Dimas Masonic Lodge No. 428 is tackling food insecurity for military families.

By Gary Kamiya

The connection to history is all around as you wander San Francisco’s Mission District. Now the center of the city’s Latino community, it was formerly a predominantly Irish neighborhood with large numbers of Scandinavians, Italians, and Germans, as well. In more recent years, it’s been the eye of the storm over gentrification and the impact of tech money on the town. While Mission Street itself has fallen on hard times, the stretch between 16th and Cesar Chavez was, during the 1950s, called the Miracle Mile—a thriving commercial district second in importance only to downtown.

Yet most pedestrians walking along Mission won’t notice one of the most significant connections to the area’s rich history. There, among the check-cashing outlets, produce markets, and pawnshops, is a massive dollar store. Unless they look up, however, they won’t notice the building’s elegant Art Deco exterior, whose strikingly horizontal design elements give it a Bauhaus quality. And even if they see that façade, they might not notice the three cryptic medallions high up on its south end, including, at the top, the famous square and compass. This is the Mission Masonic Temple, where Masons have met for more than 125 years. Inconspicuously standing over the Mission, the lodge is strangely hard to spot, but a closer look provides vivid detail about the early days of Freemasonry in the American West and of San Francisco history dating back to the Gold Rush. As James Lintner, a longtime member of the lodge who now manages the building, says, “It’s amazing how much history is packed into the place. The ghosts of past members are everywhere.”

Above: An expansion of the Mission Masonic Temple in the 1930s resulted in the installation of a new ceramic tile façade featuring three Masonic symbol medallions.

That history began in 1863, when 13 Masons gathered in the small second-floor parlor of a rooming house at the corner of 16th Street (then called Center) and Valencia, out in what was then San Francisco’s suburban sticks. By that time, the city was already home to a dozen Masonic lodges, all of which met inside the newly built Grand Lodge temple at Post and Montgomery, in the heart of the “instant city” created by the Gold Rush. But as the nascent metropolis expanded, increasing numbers of its residents moved out of today’s downtown and into the outlying neighborhoods, including the rural area around Mission Dolores.

Almost all the charter members of what would become Mission № 169 lived within a few blocks of their proposed lodge. With varied and colorful occupations and often rollicking life stories, they were a representative cross-section of the working-class Mission. They included Daniel Hanlon, a ship’s carpenter who lived near the Pioneer Race Course, eight blocks away at 24th Street; Mortimer Hopkins, a policeman who lived at Valencia and 16th next to the new lodge; Nathan W. Spaulding, a carpenter and gold miner who patented an improved type of saw and later became mayor of Oakland; James H. Welch, who ran a grocery and liquor business at 16th and 1st Avenue (now Guerrero); and Henry Hock, a barber who later ran a drayage business, with an exclusive contract to deliver beer for the Mission Railroad Brewery. For these men and others who joined Mission Lodge after it formally opened in September 1863, it was far easier to have a lodge close to home. Theirs, they proposed, would be the first “neighborhood lodge” in the city.

Above: The lodge hall of the 1897 Mission Masonic Temple features several ornate details, including stamped copper doors and intricate doorknobs.

It’s easy to understand why the members would advocate for a lodge to come to them. Consider what it took to get from the Mission to downtown at the time: It wasn’t until 1860 that an entrepreneur named Francois Pioche opened the Market Street Railway, a steam line that ran out Valencia Street to 17th Street. That, in turn, connected to Mission Plank Road, which linked up with Dolores—a crumbling old Spanish quarter full of bars, bullfights, and brothels—and the rest of the Mission District.

The new lodge proved successful, and by the late 1890s, Mission № 169 had grown to more than 300 members (it would top 500 in 1900), and the decision was made to relocate to larger quarters nearer the heart of the district. The cornerstone of the new Mission temple was laid in 1897, and the building formally dedicated on December 29, with the traditional pouring of corn, wine, and oil. Another happy event took place a few years later, when the building’s mortgage was paid off and ceremonially burned. In later years, several more lodges would share space there, including Amity № 370, Bethlehem № 453, Golden West № 455, Mt. Moriah № 44, and Seaport № 500.

The new temple was—and remains—a grand affair. Lintner, who has deep connections to the lodge (his father, Robert D. Lintner, was a past master), calls it one of the most impressive Masonic buildings in the state. With its imposing copper doors, gorgeous hand-made wall coverings, chandeliers, and stained-glass windows, the room exudes dignity and elegance.

Above: The lodge room features a multicolor Eastern Star lighting motif in the ceiling.

The site was impressive outside as well: The imposing brick building featured a three-part horizontal order, large Palladian windows opening onto Mission Street, and a mansard roof. It survived the 1906 earthquake and fire. But in 1938, when the lodge was expanded, its façade was covered with the modernist ceramic tile design scheme that passers-by see today.

That’s been a point of some contention. Kevin Hackett, a member of the lodge and the architect who designed Freemason’s Hall inside the California Memorial Masonic Temple, was among a group of members interested in daylighting some of the old façade and uncovering a bit more of the building’s history. However, those changes proved impractical and were eventually scrapped.

And so the Mission Temple is simultaneously a preservationist’s dream and nightmare, a rare example of a historic building that’s too much of a good thing: a wondrous 19th-century structure, covered by a 1930s façade that’s also a significant piece of local architecture. Hiding in plain sight, the lodge is a forgotten treasure, a living link to 150 years of history in the ever-changing Mission.

Photography by:

J.R. Sheetz

Jeremy Chen/San Francisco Standard

In the San Gabriel Valley, San Dimas Masonic Lodge No. 428 is tackling food insecurity for military families.

The Prince Hall Apartments, built by the fraternal order during San Francisco’s urban renewal, are a testament to the city’s black history.

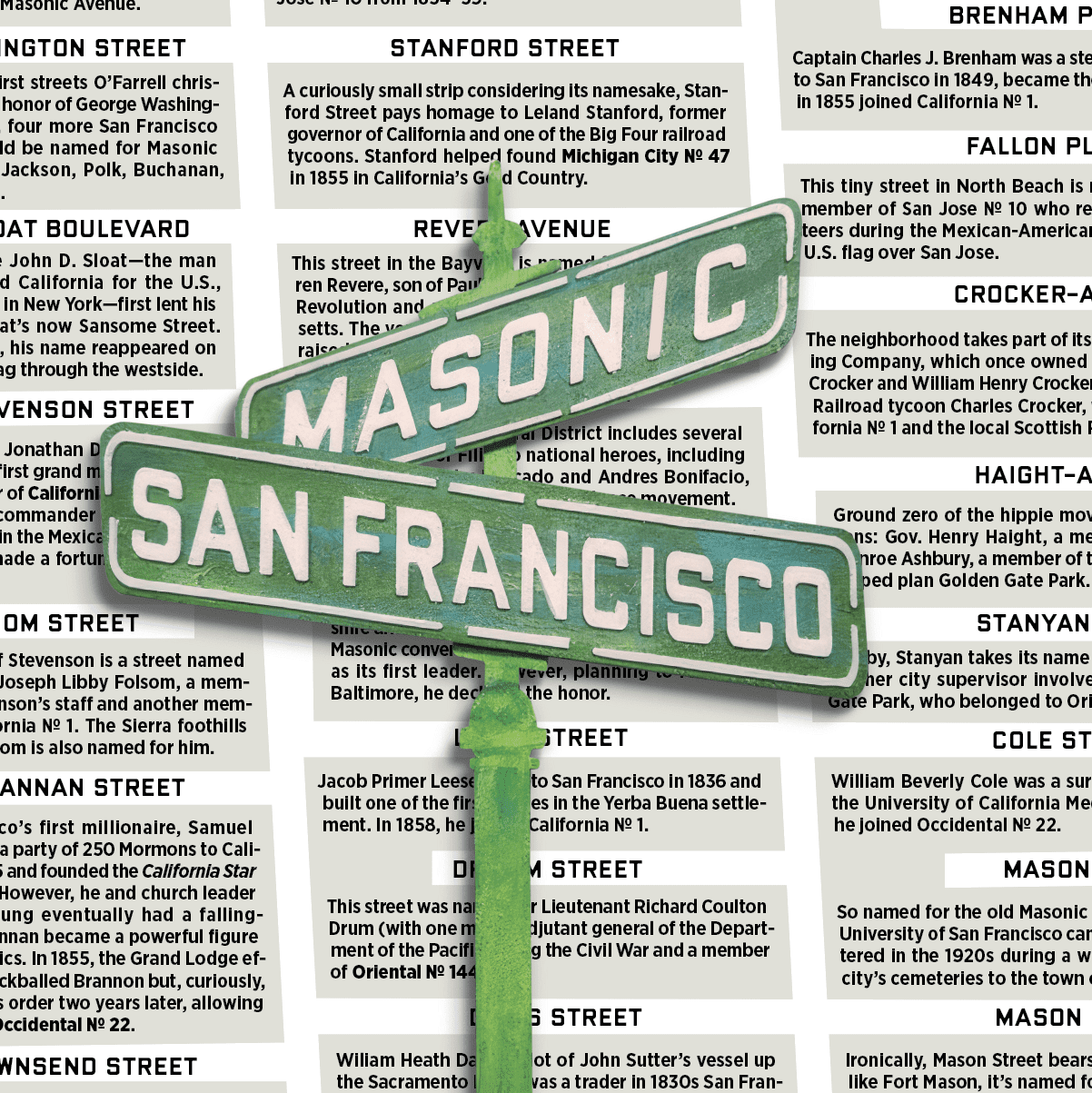

Throughout San Francisco, street names share subtle reminders of a fraternal past.