With New Breaking Barriers Exhibition, Baseball History Comes Alive

A new exhibition in San Diego spotlights Negro League pioneers, thanks to a gift from the Masons of California.

Above: Founding members of Fiat Lux U.D. under Sather Gate at the southern edge of campus at UC Berkeley. The lodge is comprised of Cal alumni. Photo by Peter Prato.

The ghosts of Freemasonry are everywhere in Berkeley. Downtown, on the main drag of Shattuck Avenue—so named for Francis K. Shattuck, past master of Live Oak № 61—the circa-1905 Masonic Temple is now occupied by the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business and tech startups. It’s largely obscured by scaffolding, but the stained-glass square and compass in the transom is still visible to curious passers-by.

One block over, Durant Avenue takes its name from Henry Durant, founder of the University of California and a member of Oakland № 268, which after his death was renamed in his honor. It’s been more than 25 years since Berkeley had an active lodge, but the echoes of its long Masonic history still ring out. Now a new group aims to revive that legacy—in large part by turning their attention toward Bro. Durant’s blue-and-gold alma mater. The state’s newest lodge, which received its dispensation this spring, will be known as Fiat Lux U.D. (The name, which means “let there be light,” is both the motto of the university and one of the central themes of the Masonic ritual.) The lodge is made up of UC Berkeley alumni, who intend to make university connections the centerpiece of their lodge culture.

While the campus-themed lodge is a new endeavor, it isn’t an entirely novel idea, at least historically. For half a century, the fraternity had a significant presence at UC Berkeley. From 1923 to 1969, it operated a Masonic student clubhouse there, built and maintained by the Grand Lodge of California, designed to serve Masonic students and the college-aged children of Masons. There was also a lodge, Henry Morse Stephens № 541, primarily serving faculty members and administrators, plus Greek fraternity and sorority houses for students with Masonic connections. Indeed, the city was once a buzzing hive of Masonry:

At its peak, Berkeley was home to six Masonic lodges, along with four Prince Hall lodges, an Eastern Star chapter, Commandery № 42 of the Knights Templar, and a bethel of the Job’s Daughters.

For all that, the true hub of Masonic activity in Berkeley, at least where the college was concerned, was the Masonic Clubhouse. It opened in 1923 to serve the university Masonic Club, formed in 1919 by members of the Acacia House fraternity, whose members were all Masons or the sons of Masons. (A sorority, Phi Omega Pi, was formed for daughters of Masons and for student members of the Eastern Star.) A Grand Lodge study found in 1920 that there were 500 Master Masons among the Cal student body, along with several hundred members of the Eastern Star and more than 60 Masonic faculty.

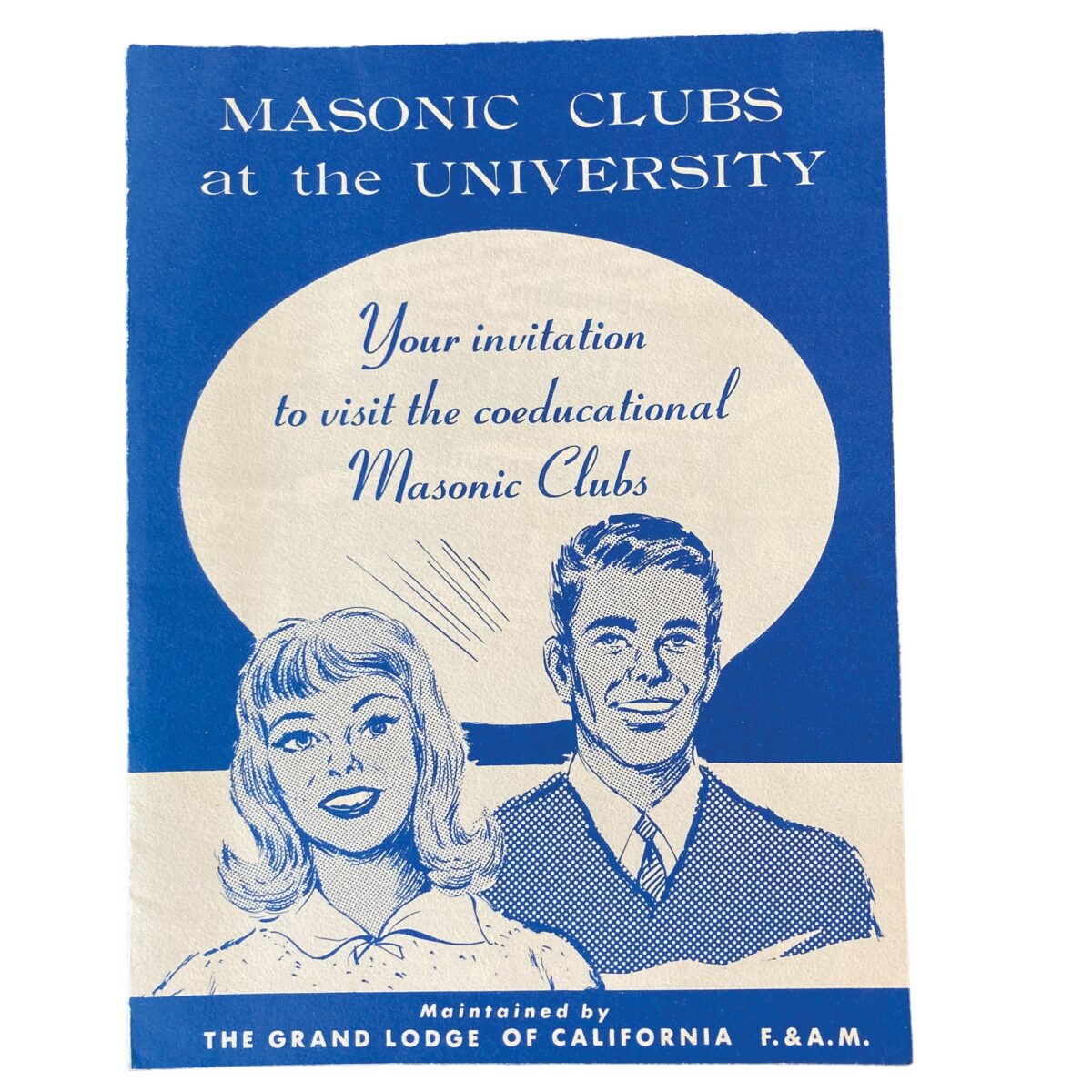

Above: The UC Berkeley Masonic Clubhouse operated from the 1920s until the 1960s on Bancroft Way and Bowditch Street. Below: A promotional brochure for the clubhouse. Image courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

The idea for a permanent clubhouse to serve those students was championed by Grand Master Charles Adams. After meeting with the students for dinner at their fraternity house, Adams wrote, “I was impressed … with the great power for good which these young men, imbued with the principles of Freemasonry, can exercise in the university.” Adams proposed erecting a permanent clubhouse where they could socialize, grow, and, as a later grand master put it, supply “as nearly as humanly possible the touch of home life and home comforts that are so deplorably absent in a great institution of more than ten thousand students.”

The idea proved popular. California Masons raised funds to cover the $102,848 cost of the site and construction for the new two-story brick building at the corner of Bowditch and Bancroft Way. On April 28, 1923—the same year that a Berkeley Mason, Friend Richardson of Durant № 268, was elected governor of California— the cornerstone for the UC Masonic Clubhouse was laid by Grand Master William Sherman, accompanied by Adams and William H. Waste, also of Durant № 268, who was a state supreme court justice and president of the Masonic Clubhouse board of trustees. The building was designed by architect Carl Werner, of Tehama № 3, who also built Scottish Rite temples in Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose, and Sacramento. It featured a Georgian Colonial exterior and included a secretary’s office, women’s parlor, lounging room, billiard room and library, and a social hall with study rooms.

The idea proved popular. California Masons raised funds to cover the $102,848 cost of the site and construction for the new two-story brick building at the corner of Bowditch and Bancroft Way. On April 28, 1923—the same year that a Berkeley Mason, Friend Richardson of Durant № 268, was elected governor of California— the cornerstone for the UC Masonic Clubhouse was laid by Grand Master William Sherman, accompanied by Adams and William H. Waste, also of Durant № 268, who was a state supreme court justice and president of the Masonic Clubhouse board of trustees. The building was designed by architect Carl Werner, of Tehama № 3, who also built Scottish Rite temples in Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose, and Sacramento. It featured a Georgian Colonial exterior and included a secretary’s office, women’s parlor, lounging room, billiard room and library, and a social hall with study rooms.

The early returns on the project were encouraging: In 1927 its board reported that the clubhouse had received more than 11,000 visitors, with one university dean noting that “the influence of Masonic activities on campus is one of the pronounced factors for good at the university.”

Above: Student members of the Masonic Clubhouse gather for a Hawaiian-themed dinner party at the clubhouse. Image courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

The clubhouse hosted several Masonic student groups, including men’s and women’s clubs, a degree team, an Ashlar Club for the children of Masons, a DeMolay Club for senior members of that youth order, a theater club, a women’s glee club, and an alumni association. The club hosted a yearly reception for the grand master and held semiannual dances, an end-of-semester social, weekly luncheons, and frequent dinners and Fireside Chats—the latter of which seems to have morphed into a “humorous and undoubtedly more enjoyable evening,” according to one annual report. In 1935, club members held the university-wide positions of student-body president, chairman of the student affairs committee, and yell leader.

The clubhouse also served practical purposes: A service committee helped new students enroll in classes and find housing, while an employment bureau helped them land jobs. Rather than form their own lodge, members tended to associate with nearby Henry Morse Stephens № 541, which opened in 1922 under William Brodbeck Herms, a noted professor who’d been responsible for the first anti-malarial mosquito abatement campaign in the U.S. So popular was the clubhouse that in 1927, the grand master proposed erecting similar clubhouses at Stanford University, the University of Southern California, and UCLA. That project was ultimately built in 1929.

For several years the clubhouses flourished, peaking at about 800 members in Berkeley in 1946. But shortly thereafter, the university saw a precipitous drop in enrollment. The club shrank to 405 members by 1950; five years later, it was at 180—while at the same time, an “increasing number of student centers are appearing on or near the campus and the effect of competition is being felt by the Masonic Club,” as was noted in one annual report. That was the beginning of the end for the clubhouse—and for Masonry in Berkeley. In 1967, the Grand Lodge reported that it was spending more than $50,000 annually to support the Berkeley and UCLA clubhouses, and proposed shuttering them both. On September 20, 1968, the UC Berkeley Masonic Clubhouse was sold for $266,000—funds that became the basis for the California Masonic Foundation’s endowment, which would take up the mantle of supporting students, this time through a statewide scholarship program.

In the rest of the city, Masonry began to evaporate, too. The same year as the clubhouse sale, Charter Rock № 410 in North Berkeley consolidated into Berkeley № 363. By the end of the decade—a time when student protests would leave their own profound cultural imprint on the city—the downtown Berkeley Masonic Temple, once the largest and most elaborate building in Berkeley, had been sold to Crocker Bank. In 1972, Henry Morse Stephens № 541 and Francis K. Shattuck № 571 consolidated; a decade later, that group merged into Richmond’s Alpha № 431. (It, in turn, became Bay Cities № 337.) In 1985, the venerable Durant № 268 consolidated into Oakland-Durant-Rockridge № 188 (now Oakland № 61). In 2001, Berkeley’s last surviving lodge was consolidated out of existence.

Into that void step the 16 charter members of Fiat Lux, who plan to meet quarterly at the Odd Fellows Temple, just steps from the Berkeley Masonic Temple and a stone’s throw from the old clubhouse site. Fred Loeser, the group’s first master, says he envisions group outings to Cal football and basketball games, as well as lodge dinners that are open to students. “As we get our legs, we’ll see if we can make a presence on campus,” he says. “You can imagine, you’re a student going through your first semester and you find out your grandfather was a Mason. Well, here we are. Come get some information about the craft.”

Despite Masonry’s long absence from Berkeley life, Loeser says he’s confident the lodge can succeed by tapping into the community’s deep fraternal roots. “We have a lot of pride as a group,” he says, “both as Masons and as guys who bleed Cal blue.”

A new exhibition in San Diego spotlights Negro League pioneers, thanks to a gift from the Masons of California.

The Masonic ritual is an elaborate production seen by only a select few. And yet Masons are committed to putting on the best show possible.

A new program from the California Masonic Foundation is introducing students to careers in green tech by partnering with Cal EPIC, formerly the California Mobility Hub.