The Masonic Homes of California, Now a Home for All California Masons

For the first time, Prince Hall Masons have access to relief through the Masonic Homes of California.

By Ian A. Stewart

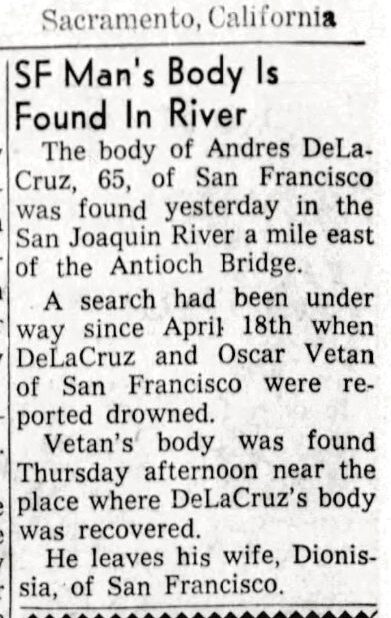

Above: Members of Jerusalem Lodge № 72 at Hannibal Hall in San Francisco, 1954. The lodge was one of several Filipino Prince Hall lodges in California until it disbanded in 1971.

Even among the thousands of photographs, papers, and news clippings that make up the Royal E. Towns Prince Hall archive at the African American Museum and Library of Oakland, one black-and-white image catches the eye: eighteen men in dark suits, arranged behind the altar, the checkerboard floor visible beneath them and Masonic rods, banners, and flags peeking out from either side of the group. It’s a pose that’s been recreated hundreds of thousands of times by lodges all around the world. Dated 1954, it’s an almost archetypal formal portrait of a Masonic lodge.

And yet this one stands out, as much for what isn’t there as for what is. The lodge, Jerusalem № 72 of San Francisco, was made up entirely of Filipino Masons. Notably, for a Prince Hall lodge, there wasn’t a single Black member. That isn’t the only curiosity. Today, there’s no trace of Jerusalem Lodge left, nor are there any other Filipino lodges within California Prince Hall Masonry. A Google search reveals nothing about the group.

The image tantalizes with mystery. It may be a perfectly typical lodge photo, but in its utter conventionality, it contains a story that tells us much not only about the history of interracial Masonry in California, but also how and where ethnic subcultures were welcomed into a statewide fraternity—and the tragic undoing of that era. In short, there’s lots more there than meets the eye.

Prince Hall Masonry is often described as a Black fraternity, but its ranks have never been closed to members of other races. (In fact, the second grand master of Prince Hall Masons, following Prince Hall, was Nero Price, a Russian Jew.) In California, that has included white, Latino, Native American, and Filipino members.

The first all-Filipino Prince Hall lodge was formed December 3, 1943, in Vallejo, near Mare Island, then home to one of the largest Naval bases on the West Coast. Vallejo at the time was a center of the Filipino American community—by 1942, there were more than 1,500 Filipinos employed at the shipyard. (The U.S. Navy offered a pathway to American citizenship for Filipino nationals.)

That Masonry would take root there is no surprise. Freemasonry has a long history in the islands and was seen as central to the revolutionary movement that ousted the Spanish in 1898. Many of the country’s preeminent historical figures, including José Rizal, Andrés Bonifacio, and Manuel Quezon, were proud Masons. In 1912, the Anglo-led Grand Lodge of the Philippines was chartered by the Grand Lodge of California, with leadership of the group initially alternating between white and Filipino grand masters. Despite that connection to California Masonry, Filipino immigrants were not typically welcomed into the larger state fraternity.

Rather, many Filipino immigrants who arrived in California formed their own Masonic and quasi-Masonic organizations. Among those were the Gran Oriente Filipino, the Grand Lodge of the Philippine Archipelago, the Legionarios del Trabajo, and the Caballeros de Dimas-Alang. Groups like these provided essential networking opportunities, as well as housing and a social safety net for men who, especially prior to the War Brides Act of 1946, almost always arrived stateside without family.

The first Filipino Prince Hall lodge, Amicus № 48, was founded by Pedro G. Tolentino, who served as its first master. In 1946, he would go on to organize yet another group, alongside Prince Hall Grand Inspector D.D. Mattocks, called Philadelphus № 54, headquartered in Stockton (home to another large Fil-Am population). It was from that lodge that Jerusalem № 72 was born.

From the remaining Prince Hall archives, it isn’t clear where or when the charter members of those lodges were initiated, whether in Prince Hall lodges or elsewhere. (New lodges typically require 13 Master Masons, including the sponsorship of a past master.) One theory is that the membership of Amicus may have already belonged to an “irregular,” or unrecognized, Masonic group, and simply petitioned the Prince Hall Grand Lodge for recognition en masse. That kind of thing certainly happened: For instance, Golden West № 83 renounced its affiliation in 1954 with an unrecognized grand lodge (named for George Washington Carver) in order to secure a new charter under the Prince Hall grand lodge.

In any case, on February 16, 1952, a past member of Philadelphus, Stanley H. Manzano, joined with four other members of the Stockton group to form the Filipino Club of San Francisco. Led by Rosendo F. Hadloc, another past master of Philadelphus, the club petitioned the Prince Hall Grand Lodge to form their own lodge, which was granted the next month. Jerusalem № 72 was chartered on October 25, 1952, along with Monarch № 73 and Monument № 74, in a joint ceremony held near Sacramento by Grand Master Starling J. Hopkins and Grand Marshall Stanley Y. Beverly.

That wasn’t the extent of the Filipino presence in Prince Hall: In 1953, another Pinoy lodge, Rising Sun № 75, was constituted in Santa Monica. And the following year, yet another, Zephaniah № 86 of Delano, in Kern County, received its charter. By 1955, an incredible five Prince Hall lodges served almost entirely Filipino constituencies.

Seventy years later, traces of that legacy are hard to find. None of those Filipino lodges remain—the result of an overall membership decline, but also of larger changes within the diaspora.

There were also local misfortunes. Amicus № 48, the first Filipino lodge, attempted to purchase land for a new meeting hall in Earlimart (Tulare County), a plan that it seems never come to fruition. In time, that lodge was consolidated into today’s Firma № 27 (Vallejo).

There were also local misfortunes. Amicus № 48, the first Filipino lodge, attempted to purchase land for a new meeting hall in Earlimart (Tulare County), a plan that it seems never come to fruition. In time, that lodge was consolidated into today’s Firma № 27 (Vallejo).

Perhaps the most unfortunate case, however, is that of Jerusalem № 72. In 1959, three members of the lodge were involved in a fishing boat accident on the San Joaquin River a mile east of the Antioch Bridge.

According to a UPI report carried in several California newspapers, Andres DeLaCruz, 65, a veteran of both world wars, lost his balance trying to net a fish and fell overboard.

Another member of the lodge, Oscar Vitan, 40, dove in after him, upsetting the skiff and sending a third member, Ruperto L. Gamboa, 70, in as well. Gamboa had been a charter member of the lodge and served as its first tyler. DeLaCruz and Vitan were both swept away in the fast-moving current as their boat sank; Gamboa was the only survivor.

Vitan’s body was discovered April 18, DeLaCruz’s a week later. An obituary in the San Francisco Examiner April 28, 1959, listed DeLaCruz’s death as occurring “accidentally near Antioch.” It also gave the name of his wife, Dionissia, and mentioned his many fraternal affiliations, including Menelik Temple № 36 (Shrine), Victoria Consistory № 25 (Scottish Rite), and Jerusalem № 72, which officiated his funeral.

The incident seems to have cast a pall over the lodge, which appears less frequently in the archival records in subsequent years. It may well have been the beginning of the end for Jerusalem Lodge. In 1971, the group formally surrendered its charter, with the reason given that the lodge could not recruit new members and that existing members were unable to meet regularly.

As for the other Filipino Prince Hall lodges, within a decade each had either folded or been consolidated. At the same time, the first Filipino lodge associated with the Grand Lodge of California, Tila Pass № 797, was chartered in 1960. Over the ensuing decades, Filipino membership in the Grand Lodge of California grew and today makes up one of the largest ethnic subgroups in the fraternity. Where once Filipino Masons had turned to Prince Hall, they began to find acceptance in the Grand Lodge of California.

Ultimately, the Filipino flash in the Prince Hall pan was short-lived, but as a phenomenon it underscored the interracial unity that fraternity fostered. That much is evident in the Prince Hall records, which paint a picture of progressive racial coalition-building. At a time when much of the country remained segregated, Prince Hall lodges were not only a haven for Black Americans, but also for all ethnicities.

Ironically, that was perhaps best seen far away from the shores of the Golden State. From 1943 through 2000, the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of California governed three lodges in Hawaii. The second of those, the aptly named Cosmopolitan № 82, was described by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1954 thusly: “The unique feature of this lodge is the multi-racial membership. It is composed of Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, Puerto Rican, Caucasian, Hawaiian, Negro, Filipino, [and] Korean ancestries and also others of mixed racial extractions.”

Writing just five years later, the lodge explained its worldview: “The name Cosmopolitan as applicable to our lodge means a brotherhood of men of multiple racial origins or social backgrounds, who ignore local or racial prejudices, attachments, and peculiarities or any of the many shortcomings of humanity by demonstrating to the world that the equality of the human race is a practical solution to many of our problems.”

Almost 80 years later, the local “peculiarities” of the fraternity have shifted, but that same animating spirit remains.

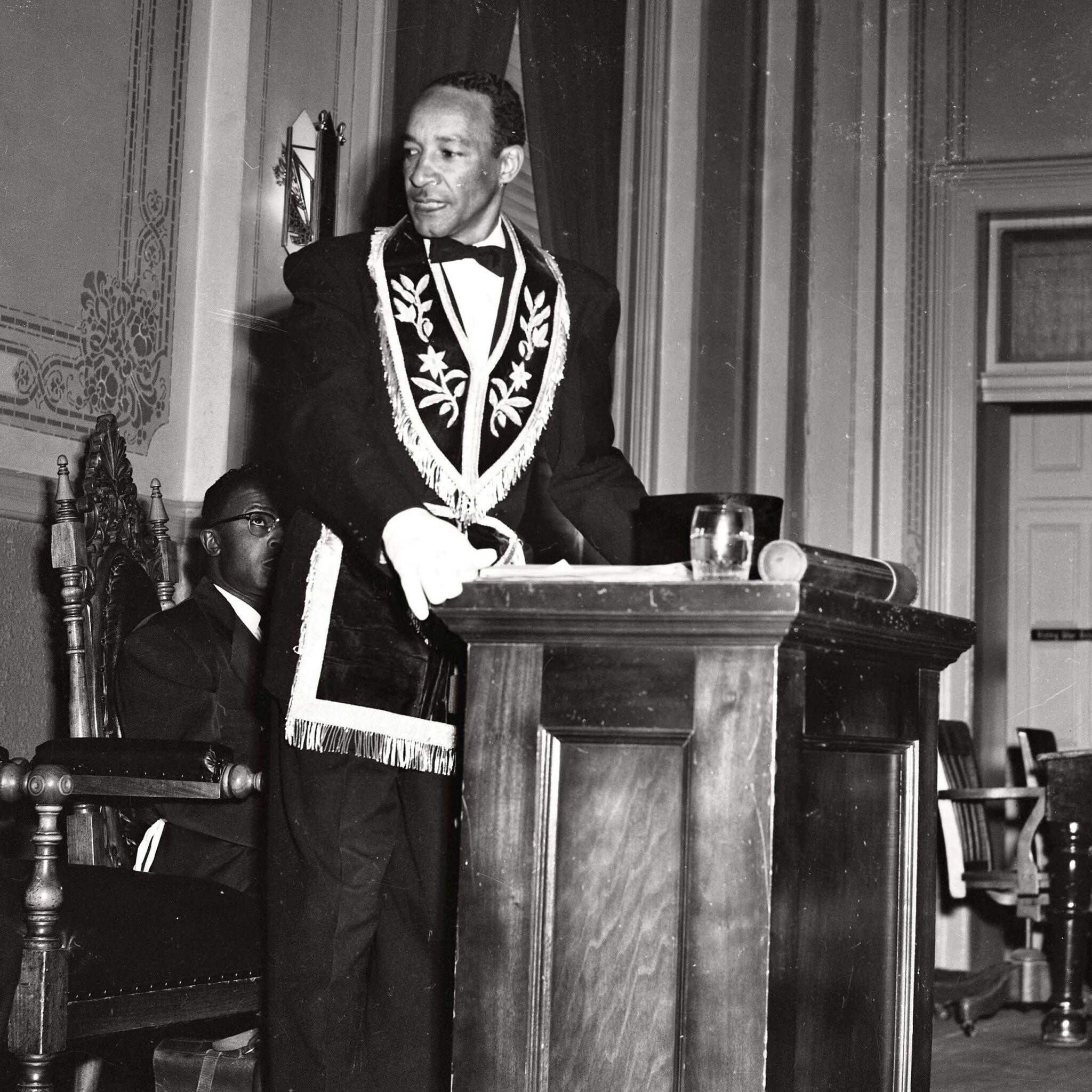

Above:

Jimmy Domingo, listed in 1958 as the only Eskimo (Inuit) member of Prince Hall Masonry in California.

Photography by:

Courtesy of the Royal E. Towns Collection, African American Museum and Library at Oakland

For the first time, Prince Hall Masons have access to relief through the Masonic Homes of California.

Largely overlooked by historians, Prince Hall remains a towering figure of both Masonic history—and American history writ large.

The most frequently asked questions about the historic branch of the fraternity.