Member Profile: Seb Badoyan

From Beirut to the San Gabriel Valley, Seb Badoyan has made a point of giving back to others.

Freemasonry’s material culture holds deep meaning for its members – and the same can be said for organizations throughout the world. Here, we look at examples of material culture within the fraternity and the wider world that convey emotional and experiential significance.

The rosary is a string of beads, gems, or pearls used by Christian worshippers to count prayers – typically the Roman Catholic Rosary. The term “rosary” comes from the Latin word for a garland of roses. As the rose is commonly used to symbolize the Virgin Mary, the meditation of the rosary is considered to be a devotion in her honor.

The rosary is a string of beads, gems, or pearls used by Christian worshippers to count prayers – typically the Roman Catholic Rosary. The term “rosary” comes from the Latin word for a garland of roses. As the rose is commonly used to symbolize the Virgin Mary, the meditation of the rosary is considered to be a devotion in her honor.

Shown here is a standard rosary, which consists of five sets of ten beads (also called “decades”) divided by marker beads, plus a set of five additional beads leading away from the strand to a crucifix. Rosary prayers begin at the crucifix and move through the decades. Each bead marks a prayer. The first bead after the crucifix is an “Our Father”; the next three are iterations of “Hail Mary”; and the last is “Glory Be.” The beads that make up the five decades each represent a single “Hail Mary” while the marker beads that separate them represent one “Our Father.”

Monarchs and deities are often seen or represented wearing a crown – an ornamental headdress. Crowns have traditionally represented authority, triumph, gory, righteousness, immortality, and sovereignty, among other powerful connotations. They are typically made of or decorated with precious metals and jewels or other rare and symbolic materials – such as rare feathers or other natural objects.

Monarchs and deities are often seen or represented wearing a crown – an ornamental headdress. Crowns have traditionally represented authority, triumph, gory, righteousness, immortality, and sovereignty, among other powerful connotations. They are typically made of or decorated with precious metals and jewels or other rare and symbolic materials – such as rare feathers or other natural objects.

Shown here is the Imperial Crown of India, worn by King George V in 1911 while acting as Emperor of India. Formed from a frame of gold-laminated silver, this exceptional piece is set with 6,100 diamonds. It is adorned with emeralds, sapphires, rubies, and thousands of additional diamonds.

The sword of state is a traditional component of royal regalia and a powerful symbol of monarchal authority. Considered to be one of a nation’s crown jewels, it represents the monarchy’s might against enemies and its duty to preserve peace. As Western European empires spread in the 17th and 18th centuries, swords of state were often used to represent conquering monarchs in their absence.

The sword of state is a traditional component of royal regalia and a powerful symbol of monarchal authority. Considered to be one of a nation’s crown jewels, it represents the monarchy’s might against enemies and its duty to preserve peace. As Western European empires spread in the 17th and 18th centuries, swords of state were often used to represent conquering monarchs in their absence.

The Irish Sword of State, shown here, was used in this ceremonial capacity. It was created for King Charles II of England in 1660. The hilt (handle) was made by goldsmith George Bowers and the blade was created by William King. As the sword was designed for processional use with the point up, its decorations reflect this position. Its design includes an uncrowned harp, representing Ireland; a lion, representing England; and a unicorn, representing Scotland.

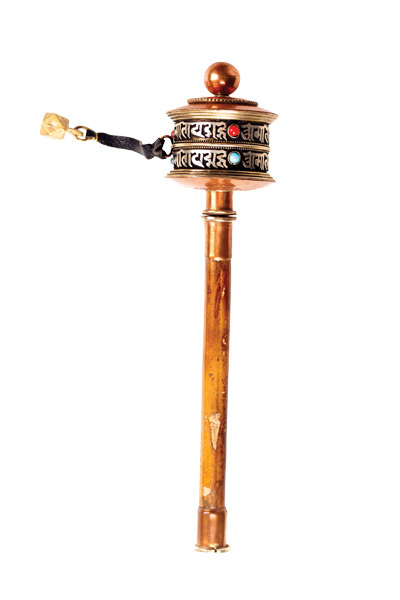

Many Tibetan Buddhists use prayer wheels, such as the one shown here, as they meditate on, and sometimes recite, mantras. The interior of each wheel contains rolls of thin paper, upon which prayers are written, wound around an axle. Tibetan Buddhists believe that mindfully turning the prayer wheel – also known as the mani – has the same spiritual benefits as reciting the number of prayers inside the wheel multiplied by how many times the wheel is spun. This action is thought to be a reflection on the phrase “turning the wheel of the dharma,” a classic metaphor for Buddha’s teachings. These often-ornate wheels originated around 400 A.D. as a tool for illiterate followers to engage with sacred texts. Large-scale versions are typically found in monasteries.

Many Tibetan Buddhists use prayer wheels, such as the one shown here, as they meditate on, and sometimes recite, mantras. The interior of each wheel contains rolls of thin paper, upon which prayers are written, wound around an axle. Tibetan Buddhists believe that mindfully turning the prayer wheel – also known as the mani – has the same spiritual benefits as reciting the number of prayers inside the wheel multiplied by how many times the wheel is spun. This action is thought to be a reflection on the phrase “turning the wheel of the dharma,” a classic metaphor for Buddha’s teachings. These often-ornate wheels originated around 400 A.D. as a tool for illiterate followers to engage with sacred texts. Large-scale versions are typically found in monasteries.

Military decorations are presented to members of a nation’s armed forces to recognize distinguished service, heroism, or personal accomplishments. They are often worn during formal ceremonial occasions, social functions of a military nature, and military holidays as a tangible expression of exemplary service. The tradition of military decorations dates back to ancient Egypt.

Military decorations are presented to members of a nation’s armed forces to recognize distinguished service, heroism, or personal accomplishments. They are often worn during formal ceremonial occasions, social functions of a military nature, and military holidays as a tangible expression of exemplary service. The tradition of military decorations dates back to ancient Egypt.

Shown here are some contemporary United States military awards. From left to right:

University students and professors display their scholarly achievements through formal academic regalia, which signifies their education level and university traditions through style, colors, and hood length. This tradition, which dates back to the 13th century, was adopted by American universities in 1895. Though it was developed for use as daily attire, today’s academic regalia is typically only worn during graduation ceremonies. Shown here is a University of Mississippi – aka “Ole Miss” – doctoral gown, which bears the school’s Lyceum logo. Widely known as Mississippi’s most famous building, the Greek Revival Lyceum building was constructed in 1848 and served as a hospital during the Civil War. It is a National Historic Landmark due to the race riot that took place there following the enrollment of the first African-American student in 1962.

University students and professors display their scholarly achievements through formal academic regalia, which signifies their education level and university traditions through style, colors, and hood length. This tradition, which dates back to the 13th century, was adopted by American universities in 1895. Though it was developed for use as daily attire, today’s academic regalia is typically only worn during graduation ceremonies. Shown here is a University of Mississippi – aka “Ole Miss” – doctoral gown, which bears the school’s Lyceum logo. Widely known as Mississippi’s most famous building, the Greek Revival Lyceum building was constructed in 1848 and served as a hospital during the Civil War. It is a National Historic Landmark due to the race riot that took place there following the enrollment of the first African-American student in 1962.

Known as the badge of a Mason, the apron is a central icon of Freemasonry. Masons don ceremonial aprons at all lodge meetings to call to mind the fraternity’s stonemason origins. The iconic North American Masonic apron is made of plain white lambskin. The addition of custom painting or embroidery on the apron varies by jurisdiction.

Known as the badge of a Mason, the apron is a central icon of Freemasonry. Masons don ceremonial aprons at all lodge meetings to call to mind the fraternity’s stonemason origins. The iconic North American Masonic apron is made of plain white lambskin. The addition of custom painting or embroidery on the apron varies by jurisdiction.

Shown here is a Master Mason/Royal Arch apron, circa 1798-1813. It is from the Antients Grand Lodge (aka Atholl Grand Lodge), which amalgamated with the Grand Lodge of England in 1813 to form the United Grand Lodge of England. The inscription at the bottom reads, “Printed for and sold by Br. Berring, Church Street, Greenwich.” The apron’s design, hand-colored engraving on silk, is based on an apron made by Robert Newman, of England, in 1798. The figures of Faith, Hope, and Charity and of the junior and senior wardens were common decorations at the time on English and American Masonic aprons. The concentric bands of blue and red silk on the border are characteristic of English aprons in the 1790s.

Photo courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry, Acc# 124.

Operative stonemasons used trowels to spread cement and join building stones. In Freemasonry, trowels symbolically unite members into one brotherhood. Commemorative trowels are often created for use at cornerstone ceremonies, during which Masons dedicate new buildings. Shown here is a commemorative trowel that was created for the 1872 cornerstone laying of San Francisco City Hall and Law Courts – a building that was unfortunately destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and resulting fires.

Operative stonemasons used trowels to spread cement and join building stones. In Freemasonry, trowels symbolically unite members into one brotherhood. Commemorative trowels are often created for use at cornerstone ceremonies, during which Masons dedicate new buildings. Shown here is a commemorative trowel that was created for the 1872 cornerstone laying of San Francisco City Hall and Law Courts – a building that was unfortunately destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and resulting fires.

The trowel is composed of coin silver with a walrus ivory scrimshaw handle. It is stamped by the popular manufacturer, J.W. Tucker, a member of California Lodge No. 1, and is believed to have been made by Tucker or his competitor, William Keyser Vanderslice – a member of Occidental Lodge No. 22. The back of the trowel is decorated with a representation of the building. On the front, it is engraved with the following dedication:

PRESENTED TO THE

M.W. Leonidas Pratt

Grand Master of Masons in California

by the

CITY OF SAN FRANCISCO

AT LAYING THE CORNER STONE OF ITS NEW

City Hall and Law Courts

22nd February A.L.

5872

The trowel is 13.5” long and 5” wide. It weighs approximately two pounds.

Jewels are another type of Masonic accessory that was popular through the mid-20th century. Jewels were typically purchased by the wearer or received as a gift, rather than bestowed by a lodge or grand lodge. These decorative pieces often showed Masonic affiliation or rank – like this example from the collection of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

Jewels are another type of Masonic accessory that was popular through the mid-20th century. Jewels were typically purchased by the wearer or received as a gift, rather than bestowed by a lodge or grand lodge. These decorative pieces often showed Masonic affiliation or rank – like this example from the collection of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry.

Charles Ernest Green gave this 33° Scottish Rite jewel to William H. Crocker in 1915, in memory of his late brother, Charles Frederick Crocker. Both sons of the “big four” railroad baron Charles Crocker were members of California Lodge No. 1 in San Francisco, like their father. William H. Crocker was president of the Masonic Temple Association; his achievements include the construction of the Masonic Hall at 25 Van Ness Avenue in 1911.

The 14-carat gold jewel has nine large old European‐cut diamonds, totaling around 2.34 carats, as well as an additional 11 smaller diamonds, ranging in size from 1.30mm to 2.50mm (about 0.25 carat). Its 20 large rubies average 0.20 carat each, and approximately 25 smaller rubies add 0.25 carat.

The marshal’s baton is used by the lodge marshal to direct guests within the lodge. This tradition can be traced back to English field marshals. Shown here is the Grand Lodge of California’s grand marshal’s baton. It was hand-carved from a single piece of wood and received as a gift from the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1958, in commemoration of the completion of the California Masonic Memorial Temple in San Francisco. According to Grand Lodge tradition, every successive past grand marshal has received a replica of this baton in recognition of his service. The top of the baton is engraved with the words, “The Grand Lodge of California.”

The marshal’s baton is used by the lodge marshal to direct guests within the lodge. This tradition can be traced back to English field marshals. Shown here is the Grand Lodge of California’s grand marshal’s baton. It was hand-carved from a single piece of wood and received as a gift from the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1958, in commemoration of the completion of the California Masonic Memorial Temple in San Francisco. According to Grand Lodge tradition, every successive past grand marshal has received a replica of this baton in recognition of his service. The top of the baton is engraved with the words, “The Grand Lodge of California.”

The tiler’s sword is a familiar sight at the door of all lodges. The tiler ceremoniously uses his drawn sword to “keep off cowans and eavesdroppers.” It is a symbol of his authority to refuse to admit those whom he does not know into the lodge during closed, “tiled,” sessions.

The tiler’s sword is a familiar sight at the door of all lodges. The tiler ceremoniously uses his drawn sword to “keep off cowans and eavesdroppers.” It is a symbol of his authority to refuse to admit those whom he does not know into the lodge during closed, “tiled,” sessions.

Shown here is the Grand Lodge of California’s grand tiler’s sword, which was a gift from the Grand Lodge of France in 1958. Iconography on the sword’s hilt includes the gavel, setting maul, trowel, five-pointed star, square and compass, scull and crossbones, and All-Seeing Eye. The sword’s red leather case bears a description of the gift and the date upon which it was bestowed.

The wardens columns are two columns that represent the pillars Jachin and Boaz that were erected at the entrance to the legendary King Solomon’s Temple. The senior warden’s column represents Jachin, signifying establishment, while the junior warden’s represents Boaz, signifying strength.

The wardens columns are two columns that represent the pillars Jachin and Boaz that were erected at the entrance to the legendary King Solomon’s Temple. The senior warden’s column represents Jachin, signifying establishment, while the junior warden’s represents Boaz, signifying strength.

The silver-plated pillars shown here were presented by Bro. Carl J. Lenzen as a gift to King Solomon’s Lodge No. 260 in December, 1923. They will be erected in the new lodge room under construction in the California Masonic Memorial Temple in San Francisco. (King Solomon’s Lodge No. 260 is now part of Pacific Starr-King Lodge No. 136.)

Photo courtesy of the Henry Wilson Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry, Acc# 99.23.1AB.

PHOTO CREDIT: Paolo Vescia, Satyam Shrestha, and iStock Photo

From Beirut to the San Gabriel Valley, Seb Badoyan has made a point of giving back to others.

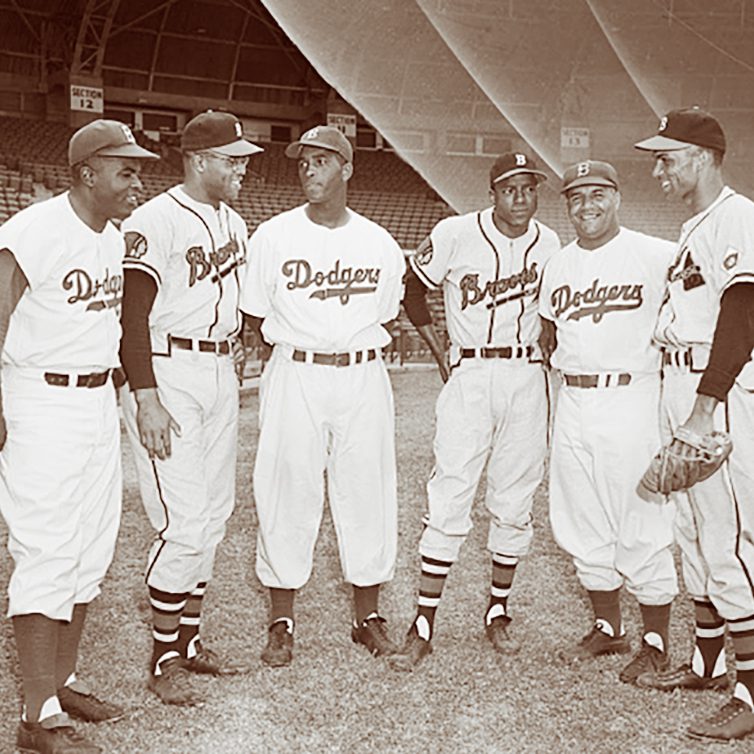

A new exhibition in San Diego spotlights Negro League pioneers, thanks to a gift from the Masons of California.

At the Masonic Family Park in Washington State, a Masonic campsite is a respite for the fraternal sojourner.