At the Chinese Acacia Club, a Cultural Legacy Lives On

For 77 years, the Chinese Acacia Club has created a space for Chinese American Masons, a historically underrepresented group.

By Tony Gilbert

Driving to lodge dinner, the news playing on the car radio is focused on the conflict in Israel and Gaza. There are also updates on Ukraine, book bans, and protests on college campuses. National strikes, gas pipeline development, housing battles, a debate over rising crime. Then there’s the election, for which the lodge will transform into a neighborhood polling place in less than a year’s time.

None of that comes up during the dinner. The Masons gathered here shake hands, smile, and exchange pleasant banter about their kids, an upcoming lodge barbecue, and the football season. At the end of the night, everyone piles back into their cars to drive home, the airwaves full again of nonstop news coverage.

One of the most famous—and famously difficult—maxims of Freemasonry is that politics and religion shouldn’t be discussed in lodge. The benefits are obvious: preserving a sense of harmony and cooperation among people from a wide range of backgrounds and with a diverse set of beliefs. But in a world in which nearly everything, from your pronouns to your vaccine status, has become a political statement of sorts, the question stands: Can anyone really avoid politics? Should they?

It’s now taken for granted that politics have become hyper-partisan, polarized, and, perhaps worst of all, all-encompassing. A simple conversation today can feel like navigating a minefield, in which erstwhile neutral topics have taken on new dimensions of divisive connotation. Given that reality, can Masons really live up to their ideal any longer? And if so, is there a secret to Masonic engagement that might be replicated outside of the lodge?

For Russ Charvonia, the answer to both is a resounding yes. Charvonia, a past grand master and member of Channel Islands № 214, has taken this issue on directly, launching the Civility Project, a series of talks, resources, and conferences aimed at helping people communicate across political divides. Since 2011, he has led civility workshops for more than 100 lodges and Masonic organizations, and his 2021 book, The Civility Mosaic, uses the framework of Freemasonry—with its working tools symbolizing patience, tolerance, and respect—to describe a new paradigm for how we can “have rational and productive discussions about hard subjects.”

To Charvonia, Masons shouldn’t avoid uncomfortable topics for the sake of politeness. “If our Masonic forefathers had that attitude, we wouldn’t have a United States as it’s designed today,” he says. In Masonry, there’s a perfect scaffolding to help members engage in precisely those kinds of challenging conversations. “We as Masons are better equipped than any other organization or society that I can think of, including religious organizations, to do this work.”

Anyway, Masons can hardly claim to exist outside the reach of politics. Consider: Among the many issues that the Masons of California line up behind is support for public schools. And yet public schools today are ground zero for many flashpoints in the so-called culture wars, from bathroom bills to critical race theory, to say nothing of larger debates around charter schools, private school vouchers, and historical curricula.

And of course individual Masons have just as deeply held stances on these topics as anyone. So why don’t lodge discussions of Public Schools Month devolve into riotous sideshows? To Charvonia, it’s because Masonry incorporates elements of reasoned debate into its core lessons. “Freemasonry, in its lowest common denominator, is a means of teaching us to treat others with dignity and respect,” he says. “All the tools, the language, how we operate a lodge room, how we respect and transfer authority—it all boils down to treating others with dignity and respect.” Marshall Goodman, of Lakewood № 728 in Long Beach, has seen that firsthand. As mayor of La Palma, he presided over contentious local debates that ran the gamut from police funding to ordinances over the color of city-approved housepaint (really). When he arrived at lodge, there was no hiding his position on those matters—they were a matter of public record.

And yet his fellow Masons didn’t try to shout him down, as can sometime happen at city council meetings. The lodge existed as a totally separate space—and it is. Because there are a different set of rules.

The chain of union bonds Freemasons together.

So how is it that Masonry is able to set aside the kinds of vicious political fights that seem to dominate every other part of our lives? It isn’t just about preserving the peace; when it comes to the prohibition against political talk in lodge, there’s a particular historical context to it.

The rules around political and religious talk are a distinctly British Masonic phenomenon. (The United States and many other jurisdictions are derived from the English tradition, and in fact Masonic lodges in many other countries take on a much more distinctly political bent.) When the United Grand Lodge of England was formed in the early 18th century, the English Civil Wars were still a relatively recent memory. There was clearly an appetite to tamp down political rhetoric within the craft.

In the United States, an additional reason to limit lodges’ political visibility was the rise of the anti-Masonry movement and the Anti-Masonic Party in the 1820s and 1830s. Many of America’s earliest leaders were Masons, including many of the Founding Fathers and framers of the Constitution, but that point of pride for the fraternity eventually soured into distrust of the fraternity. For nearly two decades, Anti-Masonry was a powerful third political party and membership in many Masonic lodges plummeted. In that atmosphere, limiting political chatter wasn’t just about polite behavior; it was a matter of basic survival.

To contemporary Masons, there’s a simpler reason to put a lid on such talk: because politics are divisive. “Politics, like religion, divide rather than unify,” says Peter Coe Verbica of Mt. Moriah № 292. Verbica has a somewhat unusual perspective on the issue: He’s a rancher, financial planner, and published poet, and in 2022 he was a candidate for the state Board of Equalization. He is currently chair of his party’s county central committee, a state delegate, and part of his state party’s executive and proxy committees. While his political platform is available for anyone to read on his campaign website, he tries to leave that behind when sitting in lodge. “As a practice, Masonry is at its best when politics are set aside and the hand of friendship and brotherly love is extended,” he says.

Or as Maynard Edwards, the host of the Tyler’s Place podcast, puts it, “The minute you’re in the lodge room, the door’s closed and we have a gentleman’s agreement not to discuss those things that are going to divide us. We put those things aside and we show up for the purpose of improving ourselves and our communities.”

That silence has echoes in the Masonic ritual. Before they take their degrees, new initiates are given time alone to meditate or ponder, in what Masons in some countries still refer to as a chamber of reflection. The initiate quiets his mind and clears a calm space, far away from the mundanities and noise outside the lodge room. The ensuing drama encapsulates the profound beauty and poetry that Freemasonry has to offer. In so many words, it marks the boundary between the profane and the sacred. Why then would we allow something so profane as politics to intrude upon our sacred inner temple?

If the inharmonious topics of politics and religion are verboten in the lodge room, what about the lodge parking lot? Or on the lodge Facebook page? There are clearly practical reasons for keeping distractions to a minimum during lodge meetings and focusing on the business at hand. But Masons interact as much outside the four walls of the lodge as within them. In Masonry and politics, is there any point trying to separate the two?

Charvonia is adamant that Masonry’s strength isn’t in simply making politics taboo. In fact, he encourages Masons to have more difficult conversations, not fewer. “When we get to a point where we bristle at talking about anything that could be politically interpreted, we’re potentially missing out on important conversations,” he says. By opening ourselves to opinions and experiences that are different from our own, we give ourselves the capacity to grow, he says.

Masonry provides a useful template for engaging with others outside of the black-and-white (or red-and-blue) framework. By taking the structure and strictures of Masonry and re-creating them in the outside world, Charvonia says Masons have a unique opportunity to usher in a new era of civil dialogue. “When I talk to Masons about how we deal with each other upon the square or how we use the compass to keep our passions within due bounds, they agree these are concepts that can work for non-Masons, too,” he says. “We should share these not in the name of Masonry, but because it’s the right thing to do.”

So how can we re-create the Masonic ideal of harmony in the outside world while recognizing that each of us still have our own set of views, values, and experiences that we feel passionately about? Charvonia lays it out like this.

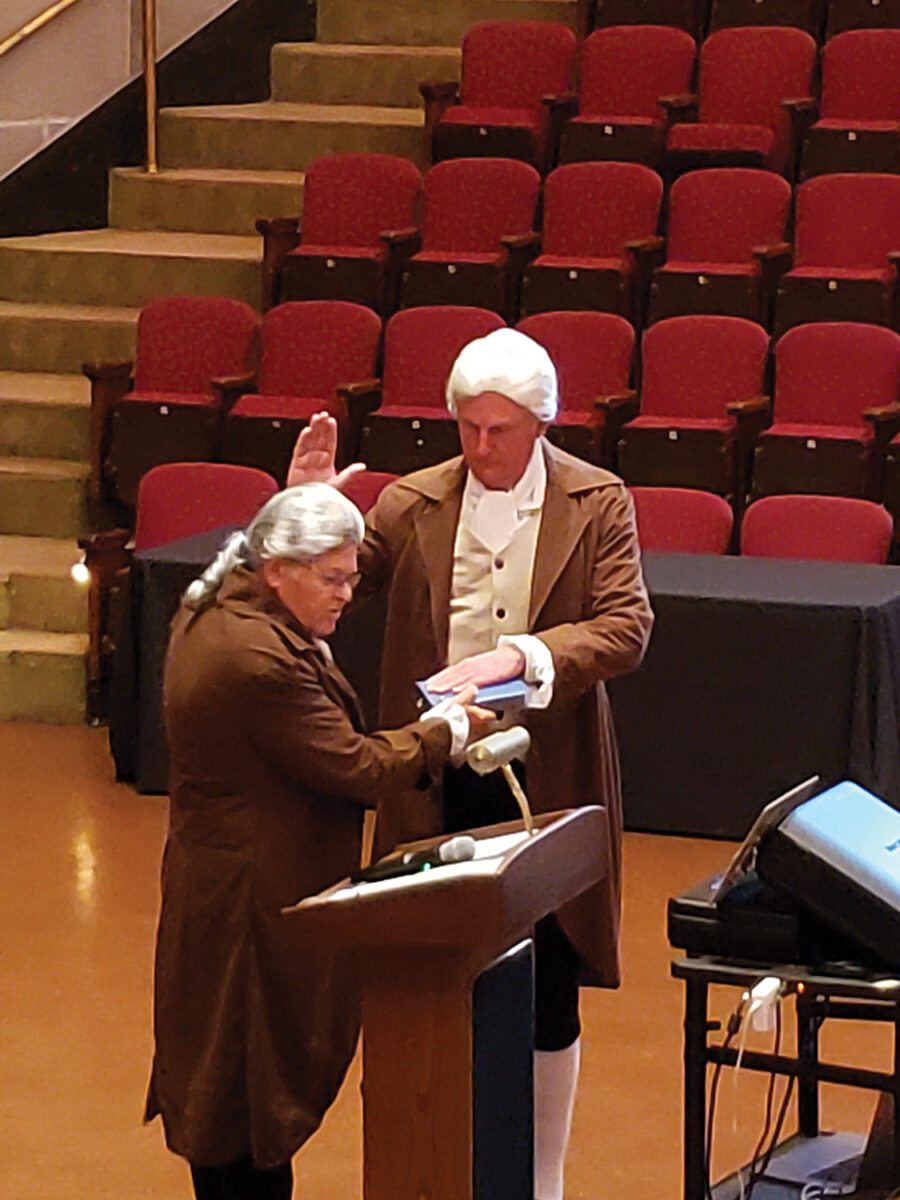

Members of Crocker Lodge No. 212 socialize at a new officer installation ceremony in Daly City.

Charvonia, who works as a mediator outside of Freemasonry, often jokes with fellow Masons about how much easier life would be if you could carry a gavel around with you and call order to conversations that were getting out of hand. But while that’s probably not going to happen, there are ways to establish rules of decorum regarding emotionally fraught issues. First, he says, suggest that parties agree to certain ground rules in order to maintain productive dialogue. Allow both parties to add more as they see fit. “Most people, if their motives are pure, tend to abide by them,” Charvonia says. So what are the rules of engagement? Use Masonry as a model: Listen patiently and don’t interrupt. Avoid framing dialogue as an argument. Allow and welcome counterpoints. Keep your passions within due bounds.

Verbica, the rancher turned candidate, points out that there’s a wide swath of unclaimed territory between the two political extremes where most people share common ground. In his political life, he says, “Rather than argue with reflexive presumptions, I try to have conversations around economic issues.” That takes the emotional sting out of thorny topics. It also allows people to start from a baseline of shared values. For instance, we all want safe and supportive schools for our children. We may disagree about how to achieve that, but if our North Star is building toward that shared goal, our conversation is building toward something concrete and not simply rehashing partisan points of conflict.

There is humanity behind someone’s politics, a face behind the mask, an individual within the group, and a name beyond the label. Politics are actually quite transitory. Platforms peter out, adjust, and swing all the time. People change and switch sides. And the causes that people were willing to die for yesterday might be forgotten tomorrow. (Try to pick a fight today about “free silver” and you won’t find nearly as many takers as you might have in 1895.) A person’s politics and worldview will be influenced by their surroundings and circumstances. So perhaps when our first reaction is to disagree with someone’s politics, we should at least recognize that what we are witnessing is the totality of that person’s experiences and perceptions, which can change.

“A lack of empathy is typically the culprit for societal and political stalemates, and we seem to have many components within our society trading empathic approaches for self-serving ones,” Goodman, the ex-mayor, says. In Masonry, members presume a level of decency in their fellow brothers, Charvonia point out. “For millennia, people have survived by making judgements about people in certain situations. But we need to flip that on its head and assume that people we’re in contact with are decent people. Occasionally, we’ll be proven wrong. But I want to be proven wrong occasionally rather than assume everyone’s a jerk.”

Masonry has much to teach us about servant leadership, says Frank Udvarhely, a member of Eureka № 16 in Auburn. Udvarhely is the district representative for an elected member of the Placer County board of supervisors. Before that, he served with numerous volunteer groups in his community, including the Greater Auburn Area Fire Safe Council, Leadership Rocklin, Municipal Advisory Council for Placer County, Rotary Club of South Placer, and Stand Up Placer. “It’s about service above self,” he says. “That means I’m doing something wholeheartedly for the benefit of somebody else, with no expected gain.”

Within a Masonic lodge, officer’s positions and the elevated titles that come with them, like worshipful master, aren’t about praise and plaudits. They’re about an obligation to act in service of the group. Plus, by placing others at the forefront of our thoughts and actions, people can transcend the issues that divide them. As Charvonia says, “If we’re engaged in the service of others, it’s just harder to be a schmuck.”

Goodman says the world of politics needs to take a cue from Masonry on that score.

“Politics can get in the way of public service,” he says. “I think party affiliation should be kept out of local government, because these are nonpartisan positions. There is too much important groundwork to be done to let any party matters or political strategizing get in the way of serving constituents.”

Masonry and Masonic lodges provide an opportunity for members to take on the problems they see in their own community, often without the baggage of national politics attached to them. (Whatever you think about the curriculum of your local schools, we can usually agree that handing out school supplies to kids is a good thing.) Lodges give us a forum to do that, locally and statewide through the California Masonic Foundation. That kind of public service isn’t partisan.

And, not for nothing, it feels good: “We feel better about ourselves when we do for others,” Charvonia says. “Feeling like you’re part of the solution is liberating. If you can do some good, taking action matters.”

Charvonia recalls his time as grand master, during which he would organize a day of public service to accompany every visit he made for a cornerstone ceremony or golden veteran’s award. Almost a decade later, he can’t recall many of the particulars about those Masonic events, but he remembers the beach cleanups, the soup kitchen volunteering, and the tree plantings. In fact, he still gets messages from Masons with photos of some of those trees and a note about how much they’ve grown. “That’s your common ground,” he says. “That’s working for a greater good.”

George Washington may be the most famous Mason in American history, and Masons have gone to great lengths to highlight the bond between him and his brotherhood. So perhaps they should look to him when thinking about how to approach handling politics in their own lives.

Washington did not belong to any political party— he’s the only American president not to. In fact, Washington was quite clear about his stance on partisanship in his Farewell Address, published in 1796.

[T]he spirit of Party […] serves always to distract the Public Councils and enfeeble the Public Administration. It agitates the Community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot & insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence & corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. [Parties] are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the Power of the People, & to usurp for themselves the reins of Government.”

Curiously, Washington’s fears for the young were not necessarily existential threats, but rather internal threats within people’s hearts and souls. He speaks about “jealousies,” “animosity,” and “riot,” which all come about when passions run wild.

Sound familiar? Learning to subdue one’s passions and to seek harmony are precisely Masonic virtues, and the restraint and self-mastery that are extolled in Masonry stand in contrast to the hubris and blustering Washington warned against. Each of us individually can choose to subdue with restraint our raw emotions or allow these to smolder into all-consuming flames. Almost 230 years later, that admonition is as relevant as ever. Just ask a Mason.

PHOTOGRAPHY/ILLUSTRATIONS COURTESY OF:

Frank Stockton

Mathew Reamer

Winni Wintermeyer

For 77 years, the Chinese Acacia Club has created a space for Chinese American Masons, a historically underrepresented group.

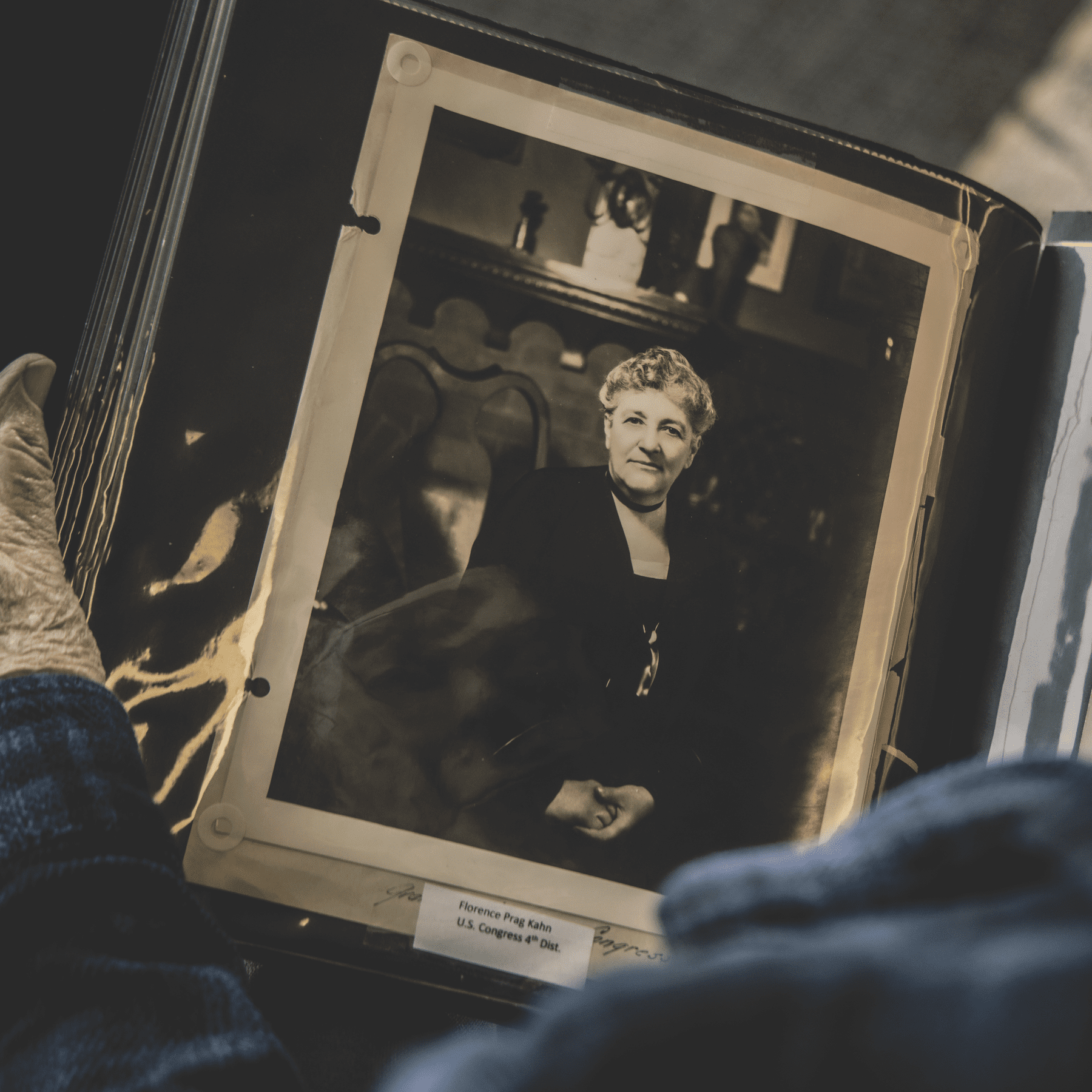

When a monument to his grandfather came under newfound scrutiny, Julius Kahn used the opportunity to shine a light on a lesser-known familial legacy: Florence Prag Kahn.

A Masonic trip to Hungary forges connections across borders.