Strong as Ever, 100 Years Later

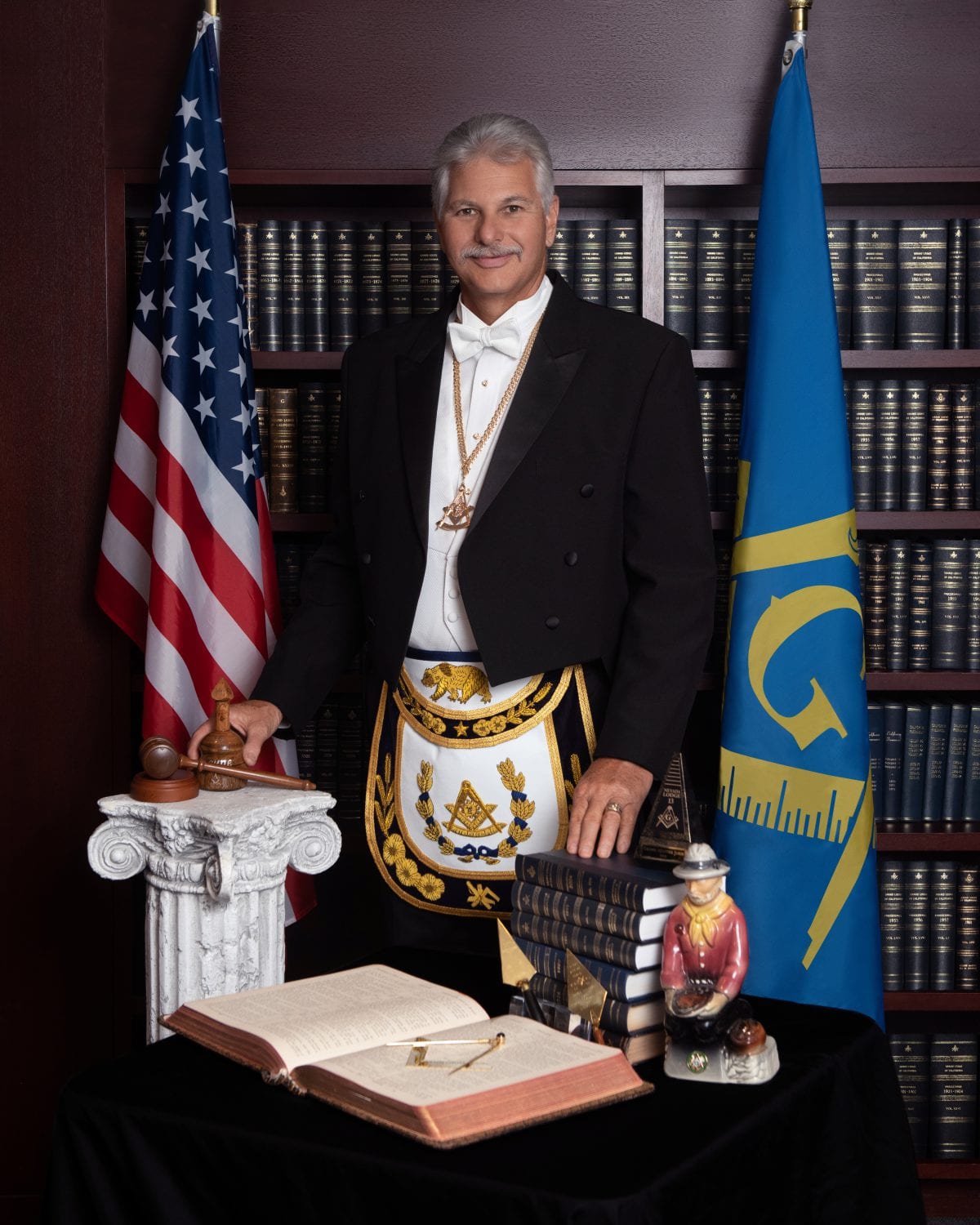

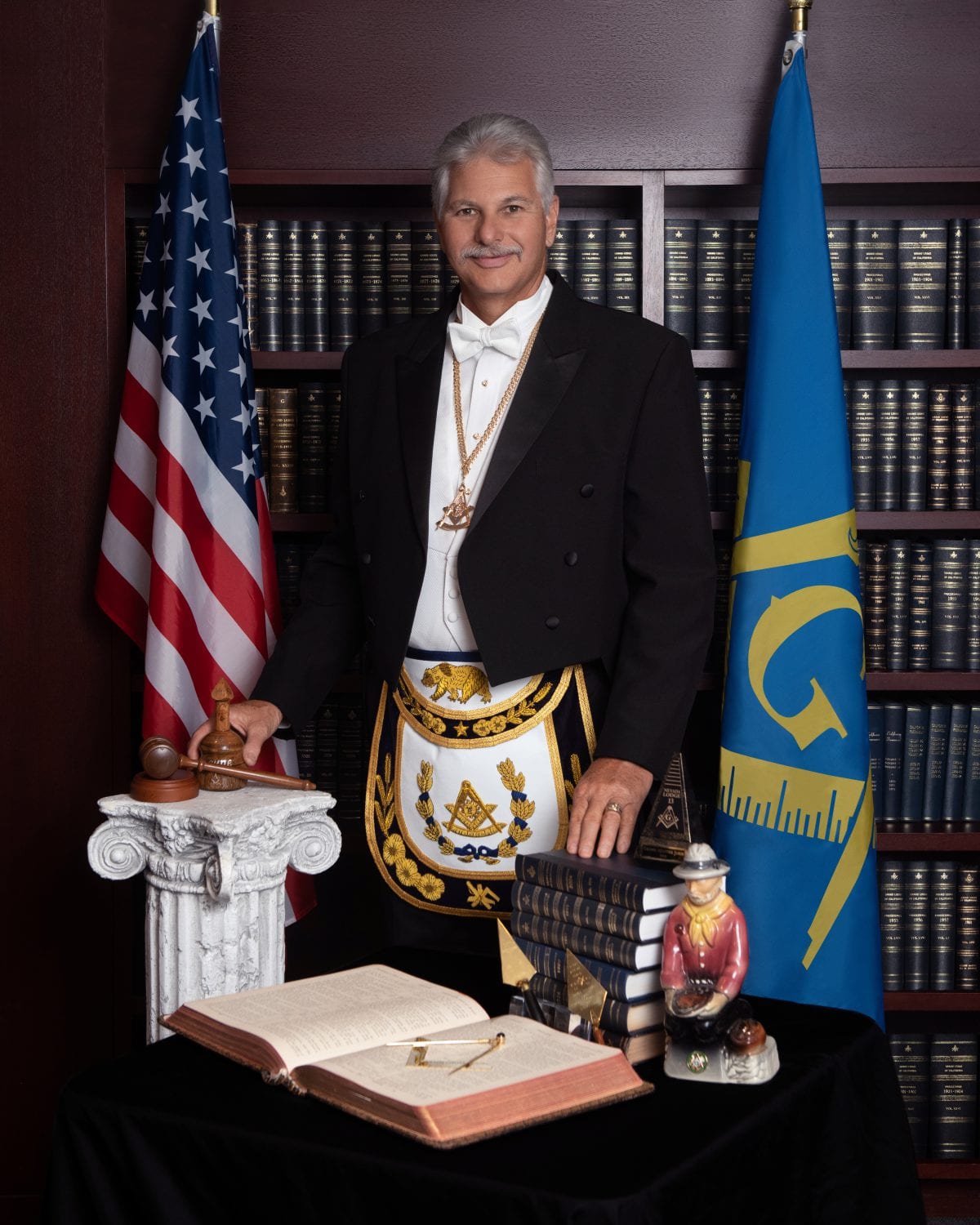

Grand Master John Trauner reflects on the historical precedent for Masonic support of public schools.

By Ian A. Stewart

Jim Dierke was a senior at San Francisco’s Lincoln High School in 1966 when he remembers the Masons walking in through the door. All week, lodge members had fanned out across the city and state to deliver prizes, awards, and scholarships to students from elementary school to high school—one of the largest public-awareness campaigns of its kind anywhere. For Dierke’s class, the nearby Golden Gate Lodge No. 30 had sponsored an essay-writing contest on George Washington and were giving away prizes. It wasn’t at all unusual: By 1966, Masons were practically a fixture in local schools each April. “They were just everywhere,” Dierke recalls.

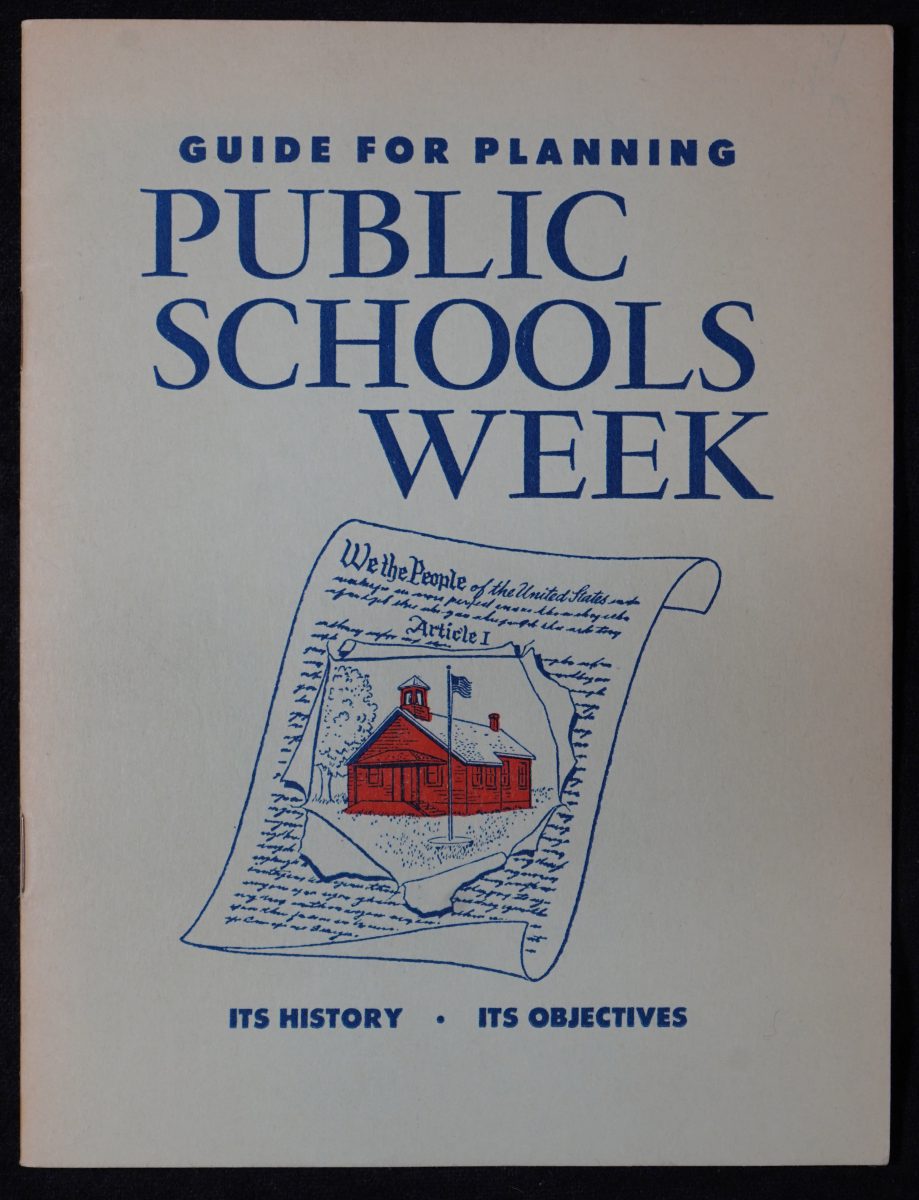

In fact, the year Dierke graduated high school, the Masons of California printed, shipped, and distributed two tons’ worth of posters and stickers advertising the fraternity’s statewide Public Schools Week campaign. The logo, which was designed by students at the LA Trade Technical College, appeared also on the side of milk cartons; meanwhile, television stations ran half-hour-long interviews about the campaign with Grand Master Theodore Meriam, himself a board trustee of the California State College system. Members of the Order of DeMolay handed out 25,000 Public Schools Week bumper stickers in California; lodge members hung more than 100,000 posters across the state. Four supermarket chains included Public Schools Week announcements in their advertising circulars. A year later, the Masons would run Public Schools Week advertisements on 100 billboards and on the sides of more than 1,000 buses, and form a subcommittee dedicated to getting Masons elected to local school boards. There was, in short, no missing how invested the Masons of California were in their public schools.

Today, 100 years after Grand Master Charles Adams first proclaimed the formation of Public Schools Week in California—later to become Public Schools Month—Masonic support remains a bedrock principle of the fraternity. And while the scope and scale of that support have waxed and waned over time, the guiding principle behind it has not. Nor, unfortunately, have the problems facing students been resolved; in many ways, California schools are in a similar crisis as they were in 1920.

This April, the Masons of California are celebrating the 100th anniversary of Public Schools Month in California, an important milestone and an opportunity to celebrate what has been a singular legacy of community support. It is also an opportunity to redouble the fraternity’s commitment to a cause that has animated its members like few others.

The issue has been central to Masonry since the very beginning. Long before the advent of Public Schools Month in California, American Masons had been closely connected to the cause of public education. That relationship begins with Pennsylvania Grand Master Benjamin Franklin’s founding of the Publick Academy of Philadelphia. Other early Masonic champions of public schools included North Carolina Grand Master William Davie, who helped launch that state’s first public university; Horace Mann, who founded the state board of education in Massachusetts; DeWitt Clinton, who as Grand Master of New York established the New York Free School Society for Masonic children, which would later serve as the model for that state’s public school system; and of course John Swett of Phoenix Lodge No. 144 in San Francisco, who as California superintendent of public schools helped create uniform textbooks and is today known as the father of California public instruction.

Beyond those education pioneers, Masonic Grand Lodges in the middle of the 19th century launched 88 public colleges across 11 states, many of which were among the first universities in the country to accept students without regard for their religious affiliation.

However, by 1919, the public school systems that Masons had played an important role in forming were in shambles: The First World War meant there was a dearth of qualified teachers, as thousands had either been sent abroad or gone to work in factories. In California alone, 600 schools were closed due to the teacher shortage—and those teachers who remained were often seriously underqualified. Of the approximately 600,000 teachers nationally, it is estimated that half had no special training. At the same time, the 1919 Smith-Towner Bill began the movement for compulsory primary education in the United States. The result was that many schools were stressed to their breaking point.

It was against that backdrop that Grand Master Charles A. Adams proclaimed that during the week of September 27, 1920, public meetings would be held in every Masonic lodge in California to discuss the “question of the public schools.” In addition to raising the issue within the membership of the fraternity, lodges were encouraged to invite educators to come speak about the state of their schools and the problems they were confronting.

The move wasn’t without risk: Advocating on behalf of public schools could have been considered a violation of the Masonic prohibition against engaging in politics in lodge. However, perhaps anticipating such a response, Adams fell back on precedent. Quoting former U.S. president and New York Freemason Theodore Roosevelt at the Annual Communication of 1920, Adams said, “We stand unalterably in favor of the public school system in its entirety.” Adams couched his proclamation by stressing that “the purpose of these meetings is only to inform and advise the members of the fraternity that they may as individuals discharge their duty as citizens.”

The issue struck a chord with lodges. An “almost universal compliance” with the request was reported the following year, and according to the 1921 Grand Lodge Proceedings, “Public educators everywhere gave their earnest cooperation.”

Within just a few years, the effort had metastasized: Rather than simply consisting of a single meeting in lodge to discuss the state of the public schools and various state and local measures relating to their funding, Public Schools Week events were being held in school auditoriums and gymnasiums and open to the general public, with distinguished speakers and politicians joining the fray. Just five years after the initial proclamation, 401 lodges had held events. A year later, members of other service organizations, including local PTA groups, Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions were becoming involved in planning school-related events. By 1927, William John Cooper, the state superintendent of public instructions was traversing the state speaking at various events.

Before long, Public Schools Week had taken on a life of its own. In 1934, Grand Master James B. Gist declared that no “work” be done in lodge during that week that wasn’t affiliated with the public schools effort. The same year, a single school district whose enrollment totaled 3,300 students reported having 4,524 visitors during Public Schools Week. “Never before in the history of our schools have we ever had such an outpouring of visitors,” wrote one superintendent. The first Spanish-language Public Schools Week program was also held that year.

Over time, the events became more elaborate. Several districts set up temporary “downtown schools” during the week as demonstration classrooms that parents could more easily visit; parades, school plays, and marching bands celebrated the launch of Public Schools Week. In 1954, the Emporium department store in San Francisco devoted window space for live class demonstrations, with gawkers watching from Market Street and listening in on the day’s lesson over a loudspeaker. By that time, Masonic jurisdictions in Montana, Arizona, Nevada, Texas, Wyoming, North Carolina, and Colorado had all launched versions of Public Schools Week. In 1956, some 1.1 million people attended Public Schools Week events in California.

“Public Schools Week is completely and universally accepted!” exclaimed the Report on the Committee of Public Schools in 1960. “Public schools interest and concern by the public at large is an accomplished result of our 41 years of dedicated work. Acceptance is just the beginning. There is no stopping us in the advancement of the cause of Public Education.”

The Masonic Public Schools fervor of Dierke’s youth was, in many ways, the high-water mark of the fraternity’s civic campaign. By the time the 1970s rolled around, three long-term trends had begun to conspire against it.

The first came from within the craft: From 1965 to 1985, membership in the fraternity declined from 244,586 to 174,423—the first stage of a 50-year slowdown that is only now beginning to show signs of reversing course. With fewer Masons joining the fraternity and fewer lodges to hold events, the muscle that had powered Public Schools Week began to atrophy.

The second trend was in some ways a symptom of the event’s success: As other organizations like parent-teacher associations and school boards became more involved in organizing Public Schools Week events, local Masons took a backseat. “It became a thing where they were just providing punch and cookies to the parents who came to the classroom,” says Past Grand Secretary John L. Cooper III, a longtime teacher in San Diego schools. The elaborate event that California Masons had birthed was able to stand on its own—and, in fact, many towns held successful Public Schools Weeks without any lodge backing at all, using the Masons’ playbook as a model. As the campaign became less a Masonic one and more a community one, the fraternity’s role in mobilizing it faded, and with that, so did the enthusiasm for organizing it.

Lastly and most importantly, the system of public education in California underwent a sea change during the 1970s. The “taxpayers’ revolt” of 1978, Proposition 13, stripped local school boards of their authority to levy taxes; the result was a drastic reduction in per-pupil spending statewide. Enrollment in private schools rose from 14 to 21 percent among high-income families between 1970 and 1990; at the same time, California schools sank to 48th in state test scores. Investing in public schools was suddenly fraught. “Unfortunately, it became politicized,” Cooper says.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, successive grand masters continued to proclaim Public Schools Month each April; however, the form of that support began changing shape. In the late 1980s, the fraternity piggybacked on the Just Say No anti-drug campaign, handing out erasers, pencil boxes, and other supplies embossed with the slogan “Drugs Are for Losers.”

Individual lodges continued to honor exemplary teachers, and many underwrote scholarships for promising students. But the mass organization of Public Schools Week events of the mid-century was gone.

In 2002, the Public Schools Committee was eliminated; advocacy for public education fell under the umbrella of the California Masonic Foundation, which continued to administer scholarships and the Masonic Student Assistance Program, a financial-aid program that had launched in 1994. It wasn’t until 2010 that a new body, the Public Schools Advisory Council, was constituted to breathe new life into the Foundation’s public-schools support.

The most significant change was moving away from the Student Assistance Program and toward a new K–2 literacy program, which evolved into today’s partnership with the national nonprofit Raising A Reader. The other was the refocusing of its scholarship program on those who would otherwise be unable to attend college—what became the Investment in Success initiative. Since launching in 2010, 669 students have received Investment in Success scholarships, along with 105 Masonic youths who have received college scholarships.

The partnership with Raising A Reader in particular has been a success. Focusing on the lowest-performing quartile of classrooms in the state, the program delivers age-appropriate and expert-vetted books to schoolchildren and their families who otherwise lack access to engaging reading material. Since launching the partnership in 2011, the program has expanded into 675 classrooms in California—with a goal of hitting 1,000—and reached 82,214 children and their families. Cindy Marten, superintendent of schools in San Diego, was among the first school administrators to partner with the fraternity on Raising A Reader while serving as principal of Central Elementary in City Heights, where 100 percent of students were living below the federal poverty line. When, several years later, Marten became superintendent of the district with more than 100,000 students, she brought the Raising A Reader partnership with her. “Their investment in this program helped expand literacy opportunities not just for children but for whole families,” Marten says. “The whole mission is so beautiful and so aligned with the promise of public education.”

So far, the results have been encouraging: After one year of partnering with Raising A Reader, 86 percent of families in the Mountain View School District, east of Los Angeles, reported that they had developed a routine for reading books with their child at home. And the time they spent reading at home increased by 50 percent. Similar outcomes have played out in other districts: Baldwin Park Unified, in the San Gabriel Valley, saw at-home reading rise from 46 percent to 96 percent; Ocean View Unified in Orange County went from 49 to 82 percent. At the Rialto School District, in San Bernardino County, the number of minutes students spent reading at home with parents doubled from 14.5 per week prior to Raising A Reader to 30.5 after one year.

Wins like that are particularly important today, as California public schools are faced with chronic funding gaps. Consider, despite the state’s high per capita income, it ranks 48th of all states in staff-to-student ratios, 41st in per-student spending, and 37th in percent of personal income spent on K–12 education. According to the 2018 California Children’s Report Card, produced by the nonprofit Ch1ldren Now, the state was given a D grade for overall academic outcomes of TK–12 students. Overall, only one-third of California students tested proficient in reading, math, and science. Those rates include huge disparities between students of different income level and race.

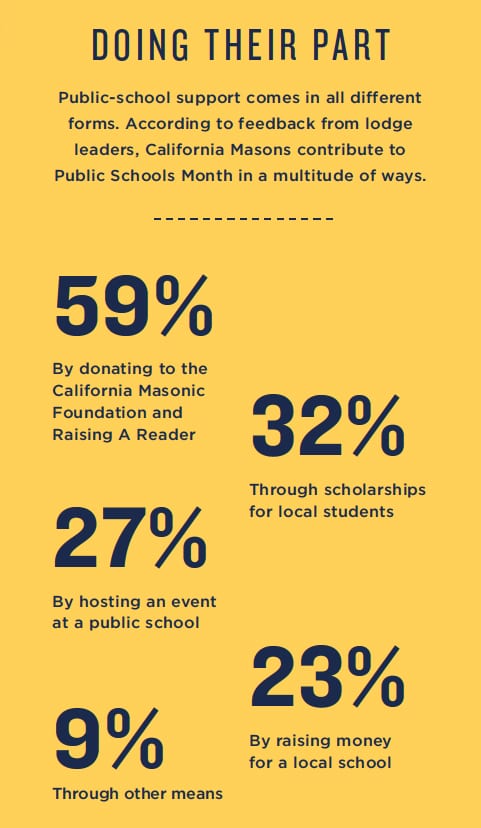

Of course, individual lodges have continued to do their part to support schools in their own communities in ways large and small. Although California public education hardly resembles the system that Grand Master Adams first fought to preserve, and the crises it faces now are of a different nature, opportunities remain for lodges to make a difference. Year in and year out, they do.

Of course, individual lodges have continued to do their part to support schools in their own communities in ways large and small. Although California public education hardly resembles the system that Grand Master Adams first fought to preserve, and the crises it faces now are of a different nature, opportunities remain for lodges to make a difference. Year in and year out, they do.

Mission No. 169, for instance, donates backpacks to incoming kindergartners—similar to a program at Washington No. 20 in Sacramento. Oakland Durant Rockridge No. 188 holds a yearly pancake breakfast to benefit Hillcrest Elementary School. S.W. Hackett No. 574 holds a district spelling bee and sponsors a Teacher of the Year prize, as does Liberty No. 299. Phoenix No. 144 members volunteer at a Raising A Reader book-distribution warehouse; Santa Monica-Palisades No. 307 partners with Scholastic Books to distribute materials to local elementary schools. Chula Vista No. 626, Glendale No. 368, and Coachella No. 476 hand out Masonic citizenship awards.

The list is practically endless.

Natoma No. 64, King David’s No. 209, Crow Canyon No. 551, and Visalia-Mineral King No. 128 all generously fund scholarships for graduating high schoolers. California No. 1 and Phoenix Rising No. 178 have adopted local elementary schools. Huntington Beach No. 380, Montebello-Whittier No. 323, and Solomon’s Staircase No. 357 recognize standout students with various awards.

Far from punch and cookies, these lodges have taken an active role in their local schools and demonstrated that Masonic support for public education is anything but a top-down directive. It’s part of lodge DNA. “One of my favorite things about the Masons is that they’re long-term supporters,” Marten says. “They aren’t fair-weather fans. Trends come and go, but the Masons are always there.”

Dierke has seen that in over a half-century in education—first as a teacher at Washington High School in San Francisco and later as principal of Visitation Valley Middle School, where in 2007 he was named the National Middle School Principal of the Year. “It all goes back to Jeffersonian thought: You have to have an educated populace in order to have a democracy,” he says. “Public schools have been the savior of our country, and I think Masons have bought into that. You can be a millionaire or a pauper, but at school you’re treated exactly the same.”

That’s something Masons can get behind.

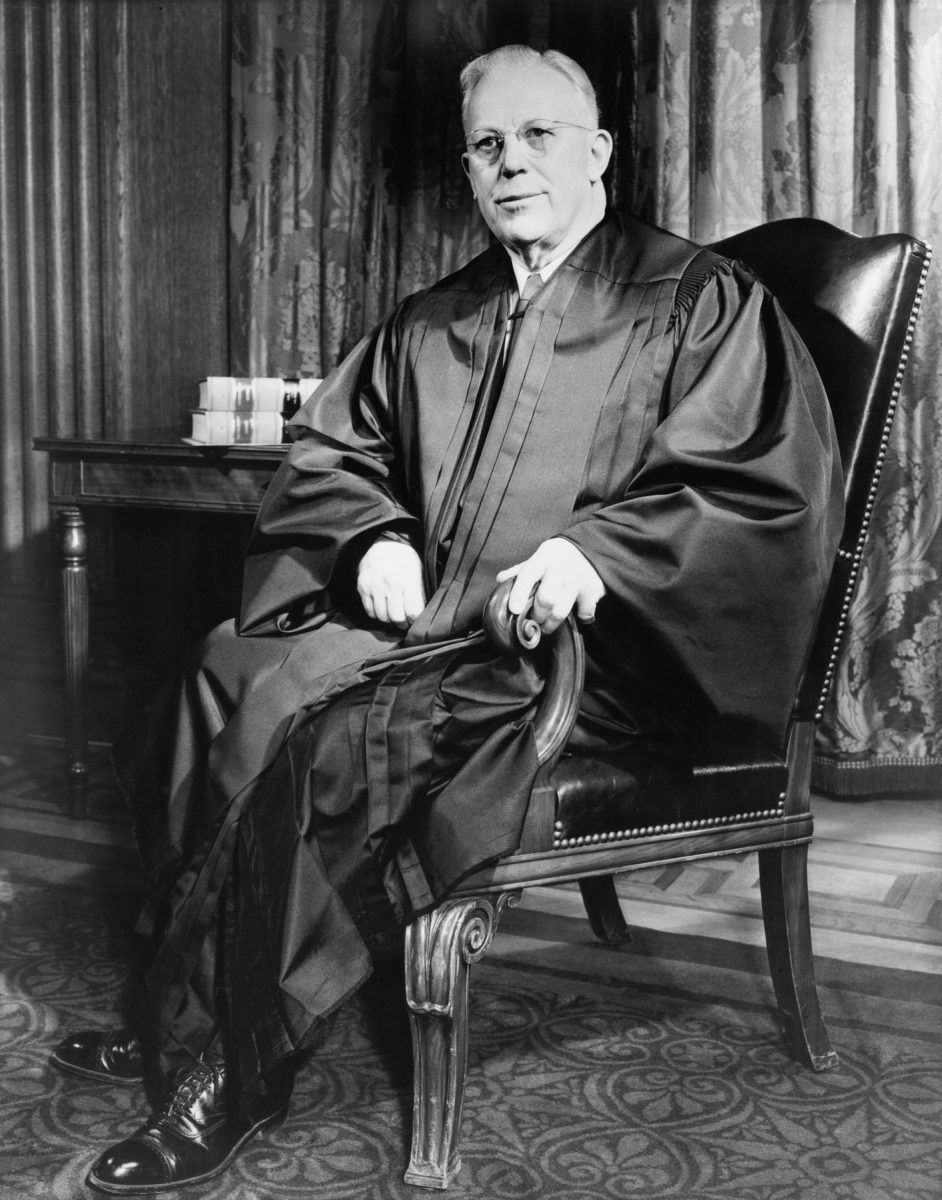

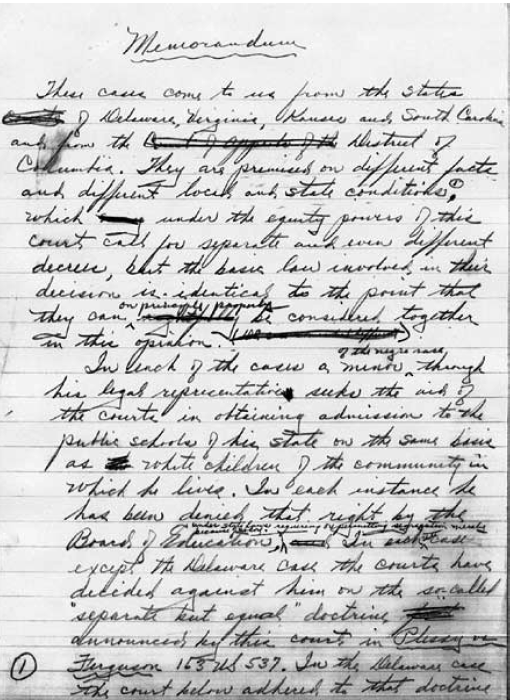

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka remains one of the most significant Supreme Court cases in the history of American education—and indeed of the country. As chief justice, Earl Warren delivered the unanimous opinion that effectively desegregated schools and represented a major turning point in the civil rights movement. A lifetime had prepared him for the moment: Nearly two decades earlier, as grand master of Masons in California, Warren, a member of Sequoia Lodge No. 349 in Oakland, expressed many of the same views in his address to the Annual Communication of 1936. At the time, he wrote, “I am convinced that the hope of the future lies in the education of our youth, not of some children but of all children—not according to so-called classes of society.”

Eighteen years later, presiding over his first case on the Supreme Court, he echoed that language: “Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it,” he wrote of public education, “is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”

His choice of words in both cases stands out. To the court, he referred to education as “the foundation of good citizenship,” and to his fellow Masons, “the foundation of a liberty-loving people—the greatest blessing this or any nation has ever had.”

Mostly, though, it’s the values that undergird those words that comes through in both texts. In addressing the Masons in 1936, Warren invoked the stonemason’s level. In the second degree, the level is described with the reminder, “For he who is placed on the lowest spoke of fortune’s wheel is entitled to our regard.” Warren wrote of public education, “It offers the strongest proof to the world that he who is on the lowest spoke of fortune’s wheel may be entitled to our regard.”

In a celebrated career that reached the pinnacle of American politics, Warren was always able to call on the lessons he’d learned—and taken to heart—back at lodge.

California Masonic Code prohibits the discussion of politics and religion in lodge. Why then, is the topic of public schools— as state-funded, taxpayer-supported endeavors—exempted from that rule?

The answer is twofold: The first concerns precedent. Masons have a long history of supporting public education in the United States, and the issue has been considered fair game. In the 1953 Proceedings, the issue is raised explicitly: “Statewide public schools’ welfare is a proper subject for discussion in lodges,” it reads. “Solicitation of individual donations for any statewide purpose concerning the protection or improvement of the public schools system may be made on lodge premises but not in a tiled lodge.”

The 1974 California Masonic Code expanded on that: “Statewide public schools welfare is a proper subject for discussion in lodges, as well as the subject of school bonds and school taxes; provided, however, that no action may be taken by any lodge to endorse, approve, or disapprove any candidate, bond, or tax issue.”

Advocating for public-schools-related measures has drawn criticism before. In 1993, the grand master argued against Proposition 174, the school-voucher initiative, writing, “Just because those with responsibilities for public education have in many places lost sight of what they are there to do, should we as Masons now abandon our public schools? No!”

The Public Schools Committee reiterated the fraternity’s stance in response to feedback to that position: “While the discussion of politics is prohibited in our lodges, public education, being the cornerstone of our freedoms, is not a matter of politics; it is a matter of our survival as a democracy.”

The head of Raising A Reader picks a few childhood favorites.

Like so many people of her generation, Michelle Torgerson loved Mister Rogers. And Sesame Street. To this day, the president and CEO of the national literacy nonprofit Raising A Reader has a special fondness for stories about neighborhoods. These days, Torgerson and her team are in the unique position of getting to share those kinds of stories with schoolkids across the country, as Raising A Reader provides age-appropriate books to children and their families from some of the lowest-performing classrooms. “A child is never too young to know that they play a special role in their community,” she says. “They are important to the ecosystem, even at a young age.”

Here, Torgerson shares a few of her all-time favorite children’s books—all of which are included in the Raising A Reader library.

—Justin Japitana

SAY HELLO

By Rachel Isadora

“This is a beautifully illustrated board book geared toward children three and under,” Torgerson says. “The book follows a young girl, Carmelita, her dog Manny, and her mother as they walk through their neighborhood and say hello to their neighbors, many of whom reply in different language. It has a simple message of kindness and friendship.”

LOVE IS

By Diane Adams

“This is an absolute favorite in our house. It takes on defining what it means to love by telling the story of a young girl and her pet duck. The story has great rhythm and rhyme and a heartwarming message about nurture and responsibility.”

LAST STOP ON MARKET STREET

By Matt de la Peña

“This book, which is beloved by many, including me, is set in San Francisco and is about a young boy and his grandmother who ride the bus through town and learn to appreciate the beauty in everyday things. I like that it’s set in a city, with a lot of great references for children who live in high-density areas—things like living in an apartment, taking the bus, and the unique sensory experience of city life.”

MY FRIENDS

By Taro Gomi

“This is a book (for readers three and under) about the things we learn from our friends. We follow a young child as she introduces the reader to her circle of friends, which includes animals, children, and even teachers. She shares with the reader what she’s learned from each of them. It has great themes about gratitude and inclusion.”

PHOTO CREDIT: Courtesy of the Henry W. Coil Library and Museum of Freemasonry

Grand Master John Trauner reflects on the historical precedent for Masonic support of public schools.

Members of the Public Schools Advisory Council reflect on the importance of public education to the fraternity.

The nonprofit American Advocacy Group executive on why charity is part of his Masonic DNA.