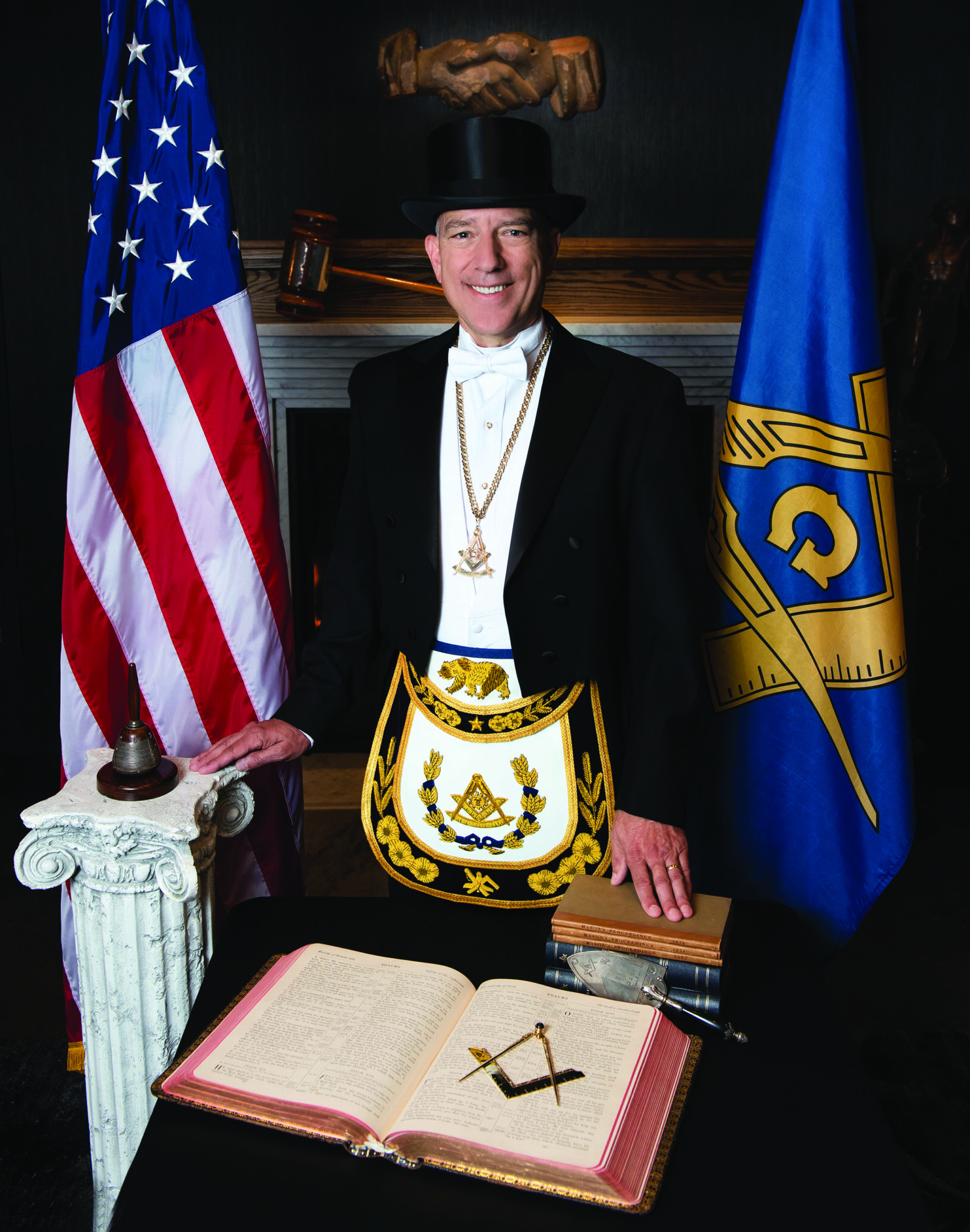

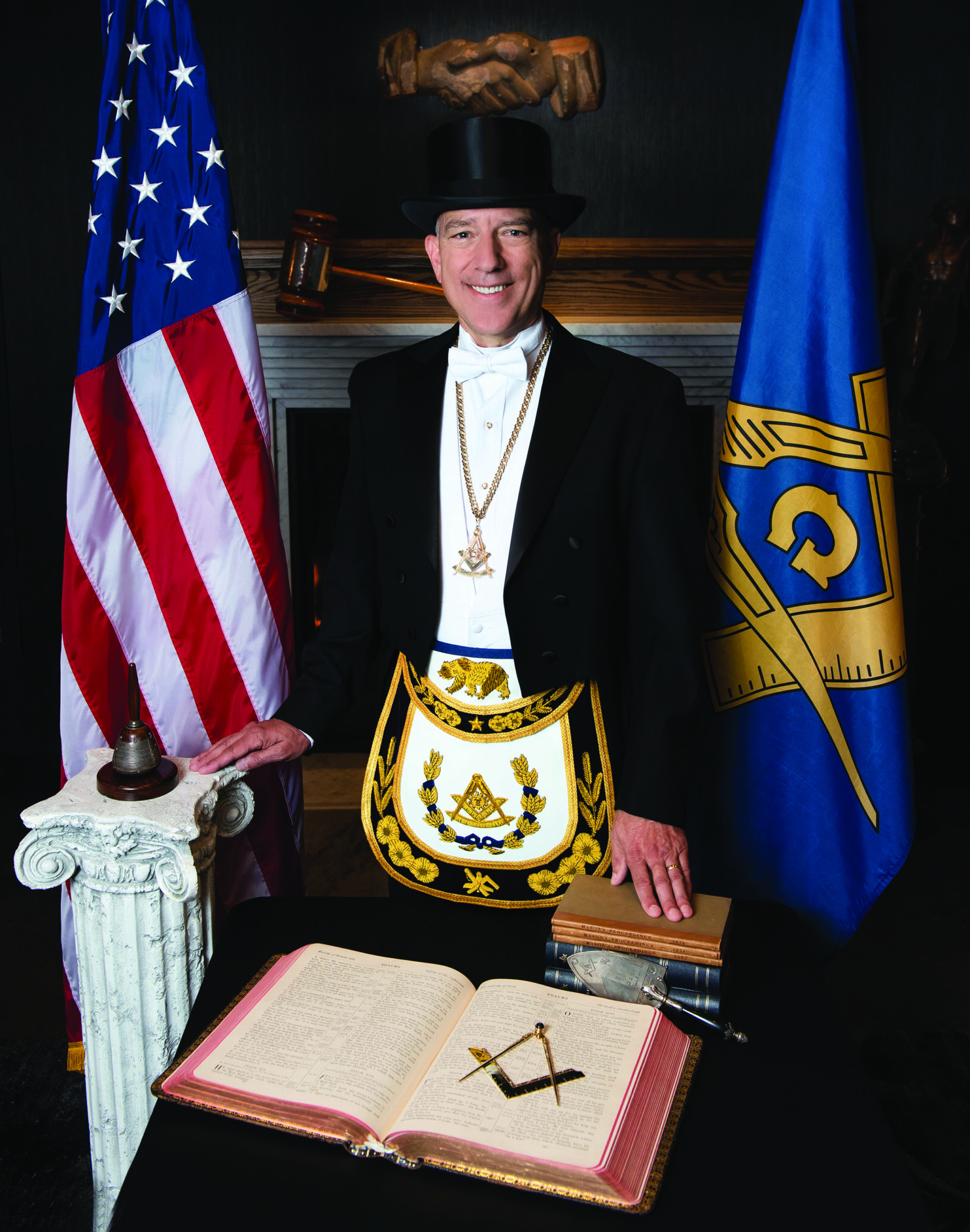

Grand Master G. Sean Metroka: What Really Matters

Grand Master G. Sean Metroka reflects on finding common ground in turbulent times, and how Freemasonry can give us a scaffolding for it.

By Brian Robin

One hundred and one years ago, the first plans were drawn up to form a lodge for Chinese American Masons in California. At the time, there were at least 20 members of Chinese ancestry living in the Bay Area, and the idea to band together into their own lodge was raised at the highest levels of the fraternity. However, rather than form a brand-new “ethnic lodge” (as the French La Parfaite Union № 17 had in 1852, the German-speaking Hermann № 127 had in 1858, and Loggia Speranza Italiana № 219 had in 1872), leaders including Grand Master William A. Sherman instead proposed a plan to affiliate Chinese members en masse with an existing lodge, Educator № 554. Once enough Chinese Masons had joined to fill the officers’ ranks, the plan was for the charter members of the group to withdraw from the lodge.

Given the time and place, it was a bold plan. From their arrival in the mid-19th century, Chinese immigrants in California, and particularly in San Francisco, experienced profound discrimination. That included having their testimony disallowed in court, enduring frequent police raids targeting low-paid laborers, and suffering the exclusion act that prohibited almost all immigration and naturalization for more than 50 years.

The plan for a Chinese lodge, as it turned out, was perhaps too far ahead of its time. The rules of Masonry have always stipulated that candidates cannot be denied membership on the basis of their race or religion, but the reality is that the fraternity has always reflected the world around it. (The first Hispanic lodge in California wasn’t formed until 1959, almost 40 years later; the first Filipino lodge came a year after that.) Unsurprisingly, then, when the 1922 Chinese plan was reviewed by Grand Lodge inspectors, “It met too much criticism and had to be abandoned,” according to John Whitsell’s history of the fraternity.

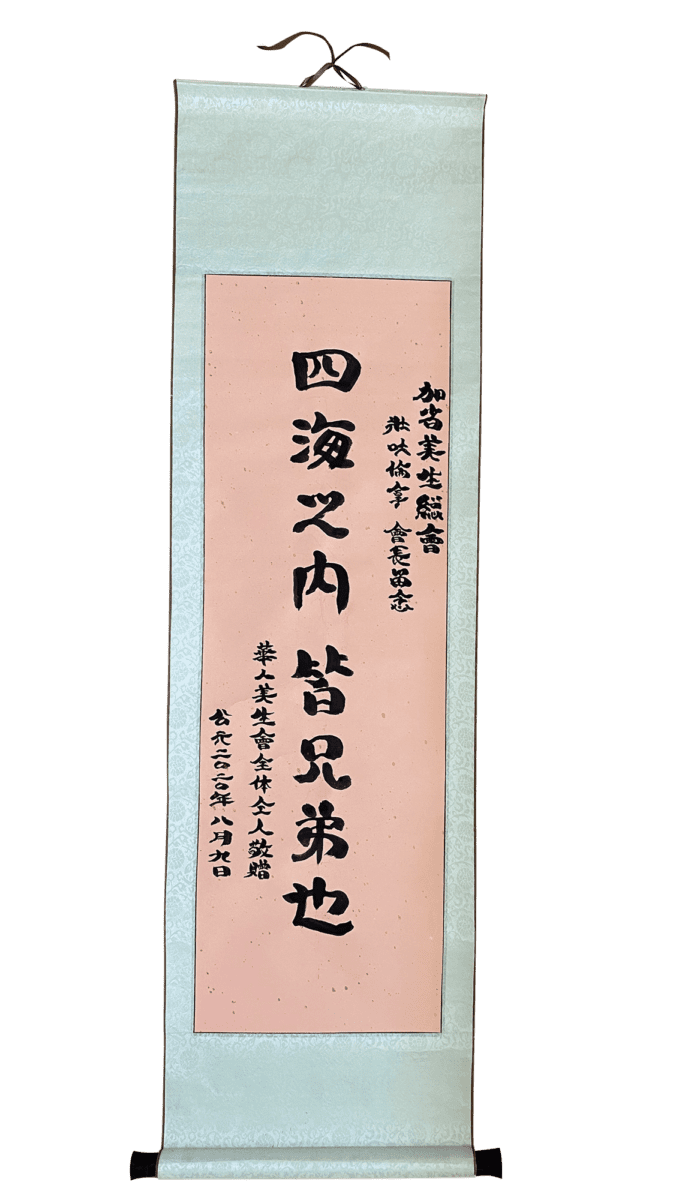

A century later, there still isn’t an explicitly Chinese lodge in California. In its place, though, another kind of fraternal home has emerged: the Chinese Acacia Club. Decades after the Educator Lodge matter seemed to close that door, another one opened. It began as many social organizations do: as a response to not having a place of one’s own—a chance to build your own house.

Today, the Chinese Acacia Club stands as a testament to the history and contributions of Chinese and Chinese American Masons in California, and also as a gathering place for members who remain part of a demographic minority within the fraternity. “It’s an extended family,” says Garrett Chan, a member of California № 1, the current senior grand warden of the Grand Lodge of California and an active member of the club. “I can call any one of our brothers to take care of my family. They’re always there to help and you can talk to them about anything—if you need advice, if you need a shoulder to cry on, if you need someone to bounce ideas off.”

The club was formed in 1946, initially as a special traveling team trained to confer degrees on fellow members of Chinese descent. The group held its first meeting at the Universal Café in San Francisco on April 12, 1946. It staged a rehearsal after dinner and, 10 days later, raised Wilbur D. Yee to the sublime degree of Master Mason at Justice № 547.

Soon, the club took on a more formal structure. On May 7, 1946, the club’s officers were elected and a constitution was drafted, with Dr. Chang Wah Lee chosen as its first president. A month later, the 30 charter members met at the Shanghai Low Café, where the stated purpose of the club was read as part of the bylaws: “To promote and foster a true and sincere Masonic spirit of good fellowship, of mutual helpfulness, of closer relationship among its members and the maintenance of a degree team to further exemplify the great ideals and precepts of Freemasonry.”

What wasn’t spelled out there—but has always been central to the group—was to provide a network of support for the relatively small cohort of Chinese Masons.

As a matter of fact, California and China do share some Masonic DNA. (Although, somewhat confusingly, members of the longstanding San Francisco Chinatown club known as the Chee Kung Tong are often referred to as Chinese Masons, although they have no connection with the fraternal order.) Before the 1930s, the few Masonic lodges to operate in China tended to be organized among American and European expats; in later years, a group of six Chinese lodges came under the jurisdiction of the Grand Lodge of the Philippines—which had received its own charter from the Grand Lodge of California. In 1943, a group called Fortitude Lodge, made up of American servicemen and Chinese nationals, received a dispensation from California to organize in Chungking, though it folded just two years later. In 1949, the former Philippine lodges reorganized in Shanghai as the Grand Lodge of China. That continues to operate today, although it has experienced periods of darkness and operated underground during the Cultural Revolution.

Stateside, the number of Chinese members has grown in California lodges. (Today, an estimated 9 percent of California members are of East Asian descent.) The Chinese Acacia Club has evolved, too. These days, it counts two past grand masters as current or former members: Leo B. Mark, grand master in 1987, and Frank Loui, in 2011. Chan, as a current Grand Lodge officer, could soon be the third. In 1985, like his father and brother before him, he was raised as a Mason by the club’s traveling degree team. “So many of the members when I was younger were like grandparents to me,” Chan says. “Sometimes there were things either in business or life that I needed someone to ask about, and there was always someone there.”

They’ve also made a point of being there for their neighbors. Since 1982, the club has given out yearly college scholarships to high school seniors—gifts that have grown to become the club’s main purpose and legacy. Along with excellent grades, Chan says recipients are chosen for their community service. “Even putting aside their scholastic achievements, they’re volunteering to help needy kids or needy elders. These kids are pouring out their souls to help others, and we want to make sure they are rewarded for their efforts.”

Service. Purpose. Legacy. Those values still define the Chinese Acacia Club. While the group has shrunk from a high of 350 members to today’s roster of about 50, little else about it has changed. Members still meet once a month at the Scottish Rite Valley in San Francisco, enjoy periodic social events, and pay a princely $12 a year in dues. “We haven’t raised that in a while,” says Loui with a chuckle.

While the meetings remain simple, “The real fun is what happens afterward,” he says—often a group meal at a Chinese restaurant. “That’s where the bonding occurs.”

Chan says that bonding is the key to the club’s existence—it’s what unlocked those doors so many years ago and has turned into a legacy of service. Says Loui, “We’ve been in existence 77 years and we’re still going. We’re still doing our part.”

PHOTOGRAPHY/ILLUSTRATIONS COURTESY OF:

Winni Wintermeyer

Chinese Acacia Club

Grand Master G. Sean Metroka reflects on finding common ground in turbulent times, and how Freemasonry can give us a scaffolding for it.

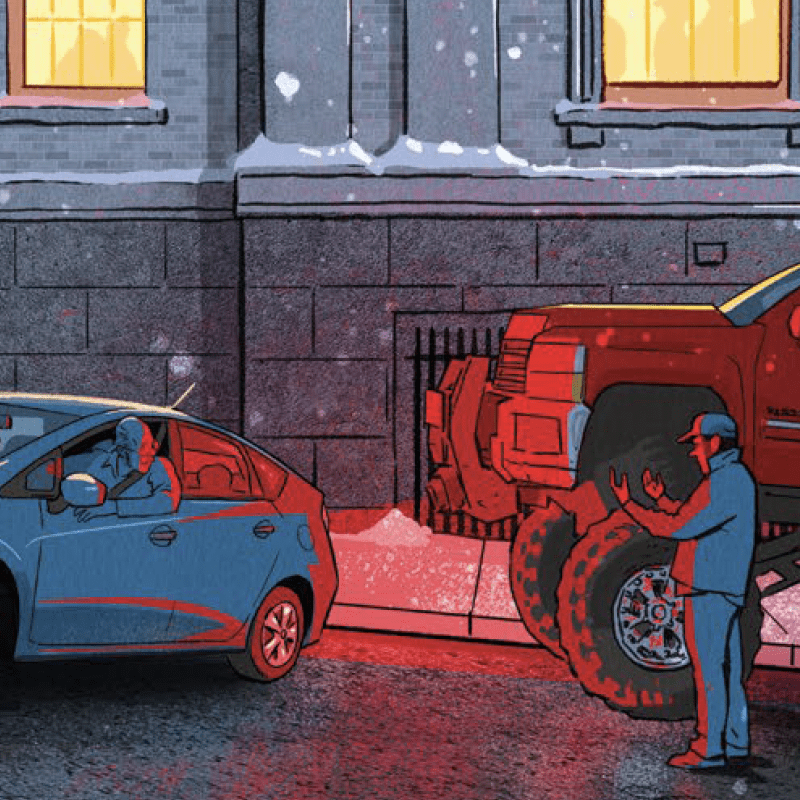

The political fights of daily life are conspicuously absent from the Masonic lodge. Can those lessons be practiced in the outside world?

A new gift from the Masons of California is helping San Diego kids go under the hood through high-tech education in growing fields.