A Conversation with ChatGPT About Freemasonry

What does ChatGPT have to say about Freemasonry? In the newest issue of California Freemason magazine, we asked the AI for its take.

By Ian A. Stewart

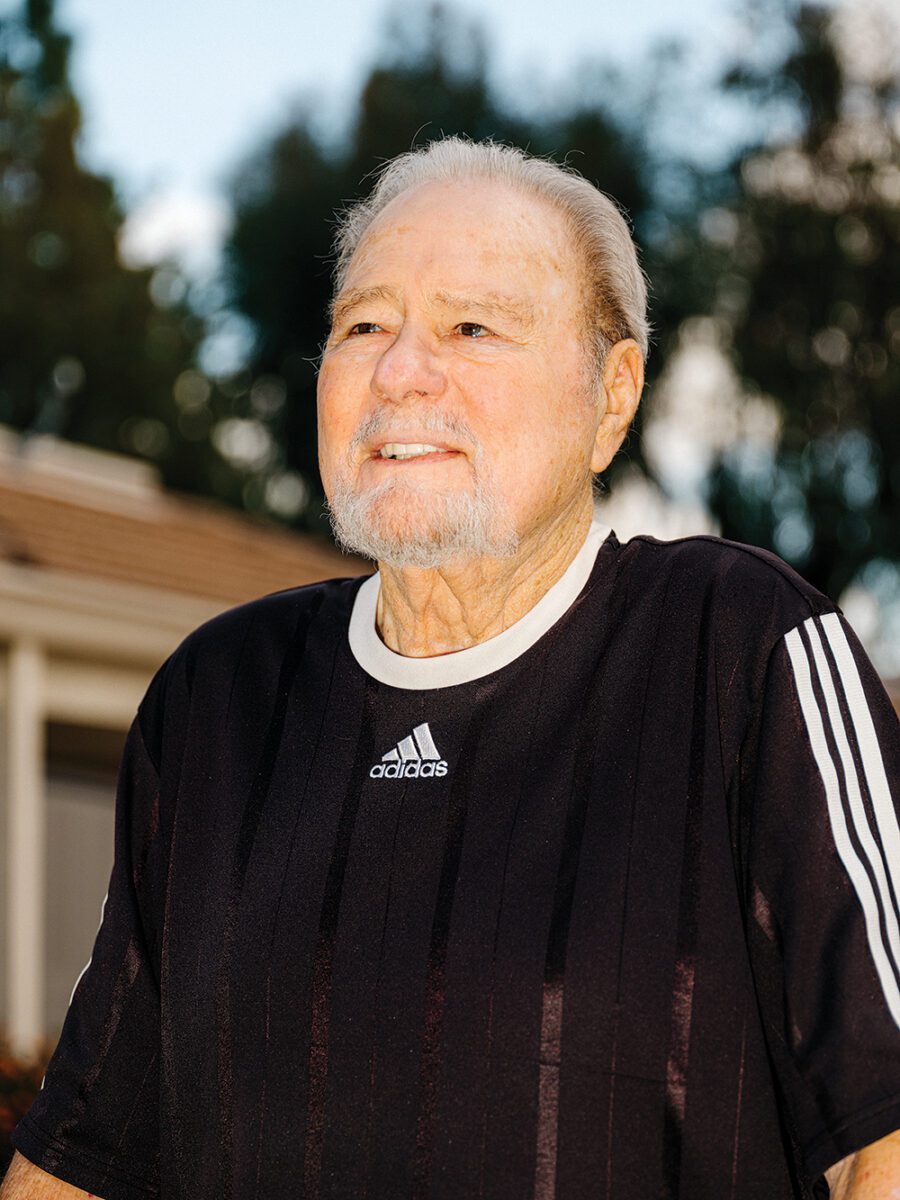

There are just a few last photos left for David Thompson to hang on his wall before he’ll declare that he’s fully bedded in to his new apartment at the Masonic Homes. But already, he’s got a nice gallery of pleasant old memories staring back at him. His new space may not be huge or luxurious, he says matter-of-factly, but it’s starting to feel like home.

A few weeks earlier, Thompson, 84, relocated from Downey to a new apartment at the Masonic Homes of California in Covina. The move happened quickly. From the first call for information to his move-in date took only a couple of months. Even the task of whittling down a lifetime’s worth of possessions and transporting the rest up to the Homes hadn’t caused too much trouble. But in another sense, the move was a long time coming.

For 15 years following his divorce, Thompson lived in a converted office space at the steel fabrication and pump-manufacturing plant he’d run for more 40 years. And a series of health issues were seriously taking their toll: a heart condition required surgery to replace an artery several years ago, and he had undergone a pair of eight-hour spinal fusion operations in his neck and lower back just 24 months apart. He’d been in and out of the hospital multiple times since. His hearing in one ear had gone, and his balance was precarious. He often worried about falling down. His son had moved into the converted office with him, sleeping on a couch in the secretary’s office in order to provide him with care. Neither of them viewed the arrangement as feasible in the long run. “My son’s got a business to run,” Thompson says. “It got to the point where [caring for me] was becoming a pain in the butt.”

So his son, also named David (but who often goes by J.R.), starting researching assisted-living facilities for his father. But the costs were astronomical. “I didn’t know how anyone can afford that,” he says.

Finally, a family friend suggested the Masonic Homes of California. Thompson was familiar with the organization from his time as master of his lodge, then called Belmont Shore № 716 (now Pacific Rim No. 567), back in the 1970s. He’d helped raise money for the Masonic Homes, but in fact had never visited the Covina campus. When he finally did, he was stunned at the size of it. “I thought, this is a lot better than where I’m living now,” he says. A few weeks later, he was finalizing paperwork to sign over to the organization a portion of his remaining assets, and a few days later, hanging pictures on the walls of his new apartment.

Almost at once upon moving into the Masonic Homes, he said, he felt a sense of relief. “Feeling like a burden to your family, having your kids put off things in their own life for you, that’s hard,” he says. “This lifted a burden off my whole family. “Right now, I just want to relax,” he says. “I worked all my life. I’m in the last few years of life, and now I’d like to just spend some time and figure out where I’m going next.”

For even the best-prepared, most grounded people, it can be hard to enter life’s final act. The idea of giving up their home, their possessions, and their sense of independence is a difficult one to make peace with. And so they don’t.

Instead, they struggle—with heart problems, or a bad back, or a sick relative. They struggle to get up their front steps, or to drive to the grocery store. They struggle to pay property taxes. Until finally there’s a crisis—an accident, a hospitalization, the death of a spouse. They reach that moment and—in the best-case scenario—begrudgingly accept the need to trade their independence for the assurance of care. They move into a nursing home.

To Sabrina Montes, though, that view is all wrong. “The entire framing is false,” she says. Montes is chief strategic officer of the Masonic Homes of California. For too long, she says, senior care has been seen as a place of last resort, where the elderly go when they’re no longer able to live independently. In reality, though, “You’re not trading in your independence,” she says. “You’re gaining it.”

Freed from the hassle of home repairs and laundry and cooking and running a million errands—all with a bad back and declining vision—the Masonic Homes allows residents the freedom to pursue the things that matter to them most in their golden years. That might be visiting with family, gardening, or traveling.

“We hear people say it constantly: ‘I wish I’d done this sooner,’” says Joseph Pritchard, the chief clinical officer of the Masonic Homes. “In the past, there was this idea that I’ve spent all my money, I have nowhere else to go, so it’s time to go the Masonic Homes. But when they get here, they realize it’s not a poorhouse. It’s a beautiful community.”

It’s a community that allows its residents to lead more fulfilled, happier retirements, Montes says. Getting people to understand that requires a mind-shift she’s on a mission to spread throughout the fraternity. “Moving to the Masonic Homes is really a wonderful opportunity for a new beginning,” she says. “That can be scary, but it’s also exciting.”

That was at least partially the case for Vernon Dandridge.

A former police officer with the LAPD and later a substitute teacher in Glendale, Dandridge dealt with health issues as a result of diabetes and kidney problems. Following the death of his wife, Dandridge, a past master of Atwater № 622 (now Atwater Larchmont Tila Pass № 614), says he struggled with his weight and nutrition. He also found it difficult to keep up with frequent doctor’s appointments, which required a friend or his daughter to drive him across town to. “I knew I couldn’t take care of myself properly,” he says.

And so, when his daughter remarried and moved out of the townhouse they’d been sharing, Dandridge decided to call the Masonic Homes.

“I felt like it was part of a normal progression of life,” says Dandridge, who was a district inspector and Assistant Grand Lecturer for several years and was keenly aware of the Masonic Homes. “It wasn’t like I was financially super hard up. I didn’t come here because I was destitute. I came because I wanted to live better.”

A year after moving onto the Covina campus, Dandridge says he’s been able to do just that. Now, he gets three healthy meals a day in the communal dining room and staff members help him manage his medication, remind him of dialysis treatments and doctors’ visits, and arrange transportation for him. “It’s much easier for me,” he says. “Living here is. a lifestyle that involves being able to do what I want, when I want. Or do nothing at all. I can kick back, relax, read a book, watch TV. I’m enjoying life again. “In my mind, moving in here is one of the smartest things I’ve ever done.”

As the new kid on the block, Thompson is still getting his bearings on campus. But like Dandridge, he’s thrived with such a robust support system in place around him. At least that’s what his son has seen.

“He’s doing fantastic,” the younger Thompson says. “One of the nicest things I’ve seen now is the physical therapy, which he’s doing every other day.” Before he moved into the Homes, Thompson says, his father never kept up with his PT—and was losing his mobility as a result. “He would have never had the energy for it while he was having to do laundry and all those other little tedious things. Now he can concentrate on getting more physically active. He’s getting to have more quality time for himself.”

Having that sense of purpose has helped the elder Thompson begin this next phase of life. Before he moved in, his son says, Thompson had “the standard reservations” about moving into care. “The biggest things didn’t have to do with the facility or the people. It was more of a pride thing.”

Just a few weeks in, though, he’s already seeing things differently.

“It’s a new chapter, and I’m learning to adapt with it,” he says. “But I’m learning a lot.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY:

Mathew Scott

What does ChatGPT have to say about Freemasonry? In the newest issue of California Freemason magazine, we asked the AI for its take.

Author and “manliness” expert Brett McKay explains how ritual helps us make sense of life’s progressions.

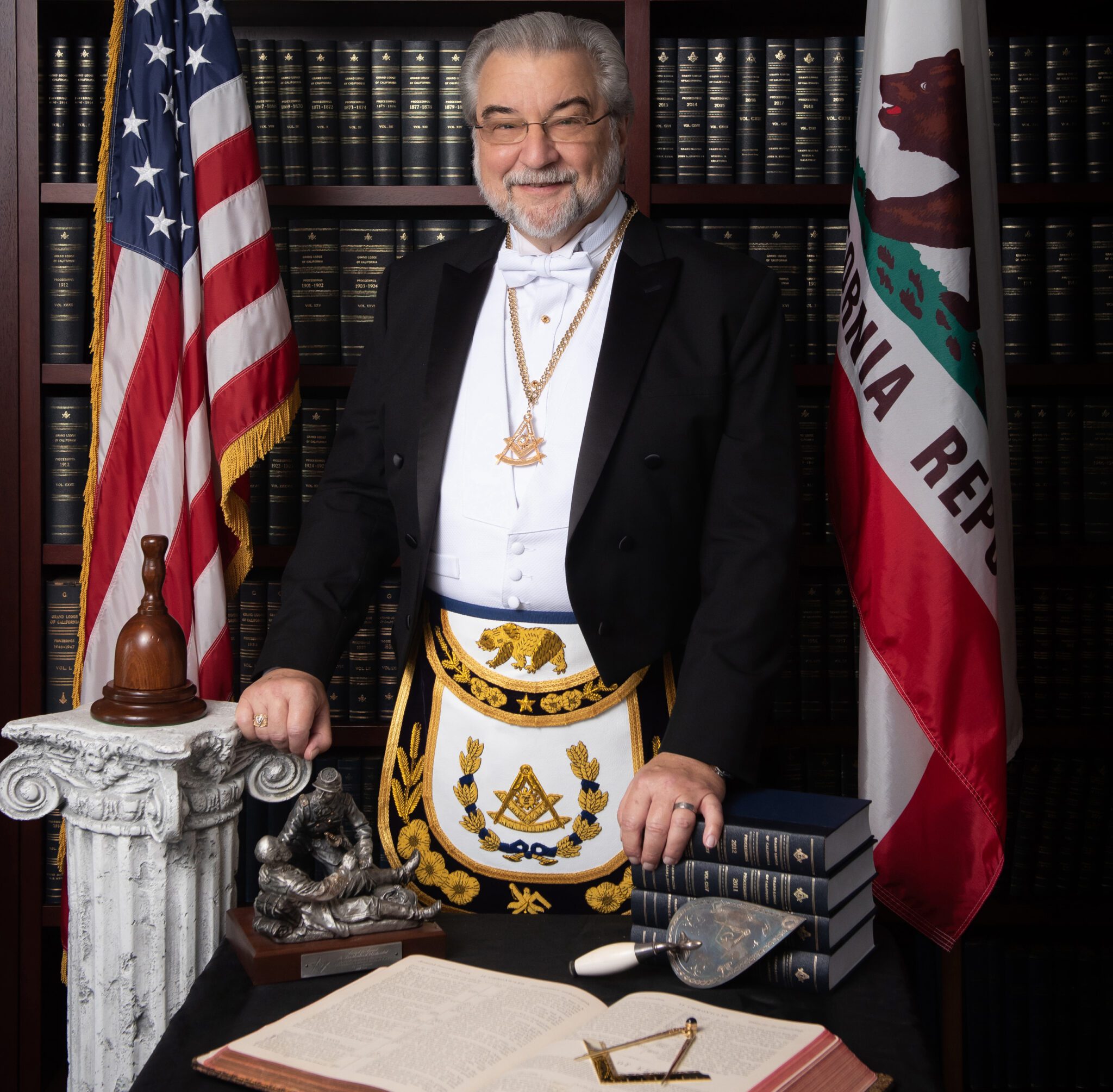

Grand Master of Masons of California Randall L. Brill explains how now’s the time for Freemasonry to begin again in California.