Grand Master Wilkins: A Grand Lodge for All

Grand Master Jeffery M. Wilkins reflects on the importance of our Grand Lodge temple—and its wonderful potential.

Not every artist is an inventor. But when it came to the massive light-filled multimedia mural that greets visitors at the California Masonic Memorial Temple on Nob Hill in San Francisco, Emile Norman’s mode of artmaking was so novel it needed a name.

Stretching practically the entire length of the temple foyer’s southern wall, Norman’s endomosaic is a stunning sight, one that for more than half a century has made an indelible impression on the thousands of visitors each year who come to the building. In scale and splendor, it’s one of San Francisco’s most impressive pieces of public art and the crowning achievement of a creative visionary. Gazing over the 48-by-38-foot work, which is chock-full of Masonic symbolism, the mind whirrs with questions. But perhaps what’s most interesting about the piece is how it came to be at all. How did a little-known Big Sur artist, working well outside the mainstream, with no formal training or any connection to Masonry, wind up creating something so integral to the home of California Freemasonry?

Ultimately, the story of the endomosaic is one of serendipity—but also of curiosity, artistic experimentation, and love.

Above:

Norman in his Big Sur studio with a panel destined for the CMMT mural. Courtesy of ENAF.

It may be that Emile Norman was destined to become an artist, but the circumstances of his childhood didn’t exactly encourage it. Born in 1918 and raised on a walnut farm in the San Gabriel Valley, he made his first sculpture at the age of 11 from a piece of found granite, ruining his father’s wood chisels in the process. “My mother kept heckling me that I should stop all that nonsense and learn an honest trade,” Norman, who died in 2009, recalled in the 2007 documentary Emile Norman: By His Own Design. “She didn’t know who I was. Never did.” But that background schooled him in other ways, and steeled his determination to succeed on his own terms.

But what really set Norman apart in his artistic career was his unlikely medium. According to the late artist’s nephew, Carl Malone, who worked alongside Norman in his later life, “He really had quite a love affair with plastics.” During World War II, when most metals went to military use, the nascent plastics industry grew as manufacturers looked for alternative materials. So while the Museum of Modern Art remained focused on traditional formats like oil on canvas, Norman was piercing cellulose acetate with a hot electric needle. A New York World-Telegram article from 1944 called 26-year-old Norman’s work with plastic “fascinating.” His great innovation, according to a New York Times review published that same year, was freeing plastic from its industrial and commercial uses and putting it to aesthetic ones.

Among his novel creations were fantastical headdresses (some of which appeared in the 1946 film Blue Skies) and decorative screens and boxes. Norman filed five patents dealing with the manipulation of plastics. “Every time I do a work of art, I learn something technically and artistically,” he said in the documentary. “I’m an experimenter.”

Although he was candid about his methods, Norman could also be very secretive—for instance, no one was allowed in his studio. He also hid much of his life from the outside world, including his sexual orientation. At a time when bar raids could end with men’s names and addresses in the newspaper, Norman closely guarded his attraction to men. That began to change when Norman met Brooks Clement, the man who’d be his partner for the next three decades. In 1946, they moved to Big Sur and began building the house that in some ways would stand as Norman’s greatest work of art.

In the documentary, Norman recalled clearing the land on Pfeiffer Ridge with glee: “That was the butchest part of my life. I loved running that bulldozer,” he said. While Norman made his art, Clement ran the Emile Norman Gallery in nearby Carmel, documented their work and research trips, and, according to newspapers of the time, “managed” Norman’s career.

Their custom-built home, with its expansive views of the Pacific, became a gathering place for friends, the starting point for hikes along the surrounding ridges, and the backdrop of their life. Tucked away from the wider world, they were free to build a life together, be open about their relationship, and enjoy the embrace of their neighbors. Beneath their living space was Norman’s studio, filled with tools, equipment, and jars of crushed glass, where he sometimes worked 18 hours a day. Over the years, his art included delicate wood-inlay panels he called Nature Poems, carved bas-reliefs, and graceful sculptures of animals created by combining wax, wood fragments, and epoxy. Precursors to the endomosaics appeared in Norman’s window displays at places like Bergdorf Goodman in New York, which sometimes included leaves and butterflies pressed between layers of plastic to create shoji-like screens. Until his death in 1973, Clement continued to assist Norman’s work; sometimes the couple signed their collaborative work “Clemile.” On the Masonic endomosaic, Clement’s name appears just under Norman’s.

Today, Norman’s work is in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Monterey Museum of Art, but the majority of his output is privately owned. Much of it never left their home. As Will Parrinello, who directed the Norman documentary, points out, “The house is itself a work of art, and it was designed to house his artwork.”

It wasn’t far from his Big Sur studio that Norman became forever linked to California Freemasonry. In 1954, he created his first endomosaic display for the Casa Munras Hotel in Monterey, depicting the history of the town. There it caught the eye of the modernist architect Albert F. Roller, who earlier that year had won the commission to design the California Masonic Memorial Temple. In 1956, Roller sought out Norman to develop a pair of show-stopping works for the temple. (In addition to the endomosaic, Norman created the large bas-relief frieze on the building’s northern face.) For David Wessel of Architectural Resources Group, who led a massive 2006 restoration of the endomosaic, part of what makes the piece special is its integration into the temple’s overall design. Says Wessel, “As a product of the plastics movement that had its genesis during World War II, it’s completely appropriate for a midcentury building. The materials, the design, and the placement in the building—everything.”

Norman had no special connection to Freemasonry. To familiarize himself, he dived into the history and symbolism of the fraternity. In 2006, he told California Freemason that he interviewed dozens of members and borrowed books about Masonry from the Grand Lodge to learn about its iconography. The finished work contains depictions of Masonic tools and symbols including the trowel (friendship), the plumb (uprightness), and the all-seeing eye (benevolence), all framing central figures representing the Masons’ contributions to California history. Norman would spend nearly 20 months working on the piece in his home studio. Executed panel by panel with the help of a homemade light table, the 45 sections, each weighing 250 pounds, were trucked up to San Francisco and put into storage until ready for installation.

Much of Norman’s other work was on a more human scale, and the endomosaic stands out for its sheer size. “I think the thing that motivated him the most was doing something he hadn’t done before,” Malone says of his uncle’s approach to the project. Norman’s process for the endomosaic differed from typical mosaic-making. Rather than apply bits of glass to an object’s surface and cement them with grout, he combined all sorts of materials and pressed them between two layers of clear acrylic. Among those used to color and shade the panels are glass, seashells, foliage, metals, thinly sliced vegetable matter, and soil collected by Masonic lodges in each of California’s 58 counties, as well as the Hawaiian Islands (then a part of the Grand Lodge of California).

The result, even when layered between flat planes, has an incredible tactile quality. Like a pointillist painter, Norman combined 180 hues of ground glass that mix optically to create graceful shading. The cohesion of the overall design is immediate. White and black outlines follow the logic of a single light source, the all-seeing eye at the top of the work.

Above:

Among the materials used to color and shade the endomosaic are glass, seashells, foliage, metals, thinly sliced vegetable matter, and soil. Here, jars of these materials line the walls of Emile Norman’s home studio in Big Sur, California. Photo by Stephen Schafer, courtesy of ENAF.

Despite the triumph of the endomosaic, which is seen and photographed by thousands of visitors each year, Emile Norman’s name has never been widely known beyond a small group of collectors. According to Parrinello, whose documentary is streaming on Kanopy, there was a moment in the early 1960s, when Norman was back east, that he could have pursued a career with a New York gallery. Instead, he opted to return to Big Sur to pursue his art on his own terms.

Before Norman died in 2009, he laid out plans for a trust to protect both his home and his art. But in 2020, bankruptcy proceedings forced Norman’s house onto the market, prompting local fears of demolition— an irreparable loss to the artistic heritage of Big Sur. Thankfully, the home, its artworks, and the 40 acres of land surrounding it were purchased by the newly formed Emile Norman Arts Foundation, funded by a silent benefactor. Heather Chappellet Lanier, Kim Stemler, and Heather Engen, the trio of Big Sur residents behind the foundation, are now working to bring Norman’s art to a wider audience.

In a home assembled over decades with love and care, the markers of Norman and Clement’s personal and professional accomplishments are finally secure. There are traces of their crowning achievement throughout the space: a scale model of the Masonic endomosaic, a life-size test panel mounted within a door, and dozens of glass jars full of soil from Masonic lodges. “It meant a lot to him, and he kept that part of his life there,” Parrinello says.

It was that dedication to his work that drew Parrinello to Norman. The filmmaker remembers their first meeting: “He said, ‘You know, no one’s ever going to give you permission to do what you want except for yourself. So what are you waiting for?’ ” Parrinello says. “That’s how he lived his life.”

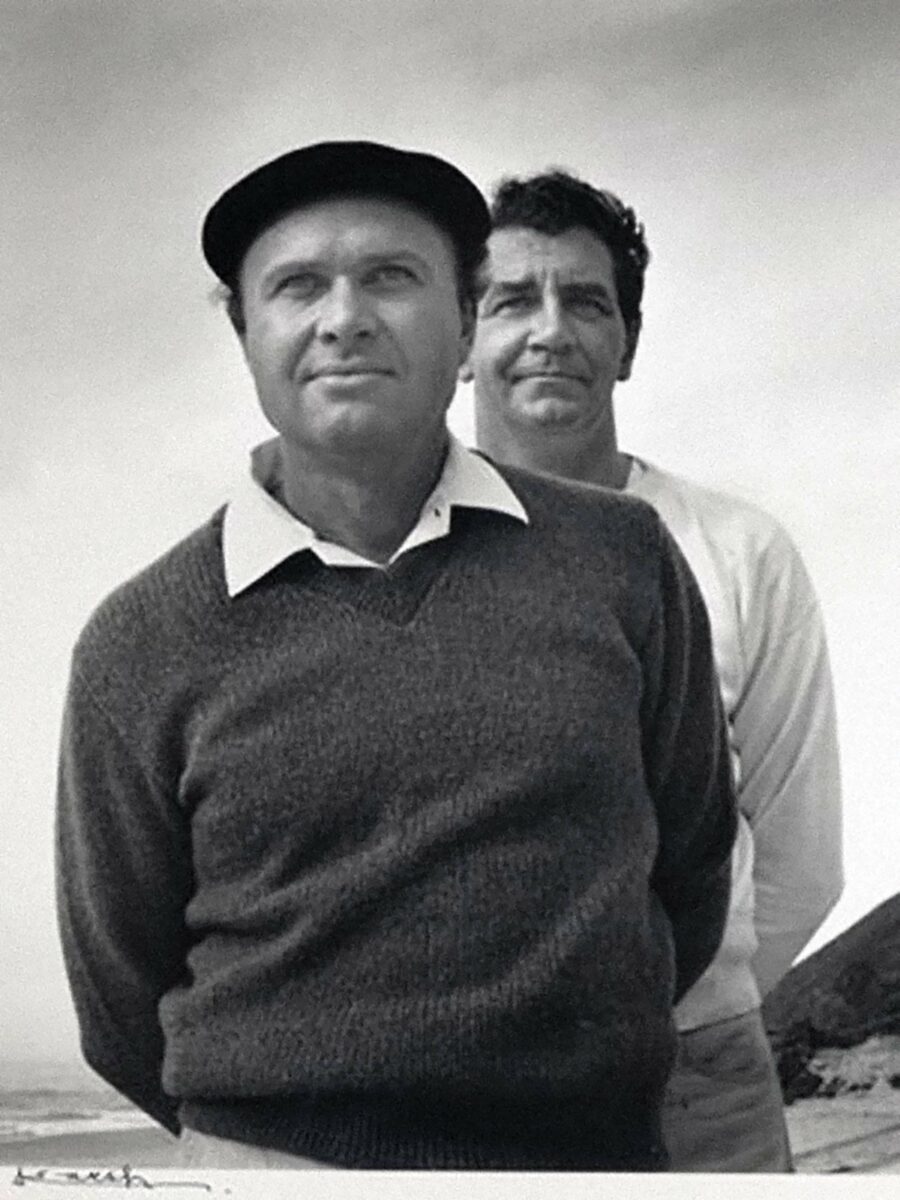

Above:

Emile Norman and Brooks Clement examine a carved marble slab in Italy, circa 1957, during research for his work on the endomosaic and bas relief frieze for the California Masonic Memorial Temple. Courtesy of ENAF.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY:

Yousuf Karsh

Courtesy of Emile Norman Arts Foundation

Liz Hafalia/Getty

Grand Master Jeffery M. Wilkins reflects on the importance of our Grand Lodge temple—and its wonderful potential.

California Masonic Memorial Temple chairman Mark Pressey has a special connection with the home of California Masonry.

The Siminoff Temple at the Masonic Homes of California has a history going back over a century.