For Rainbow Girls, a Century of Change—and Continuity

As the Masonic youth order Rainbow Girls celebrates its centennial, a look back on all that’s changed, and all that hasn’t.

The first thing you should know is that Freemasonry is a big deal in Cuba.

I was on a bus when I first began to notice it, somewhere on the road between Aguada de Pasajeros and Santa Clara. It was a hot, dusty day, and as the antique vehicle chugged along, I gazed out the window, watching a rolling landscape of yellowed grass and palm groves, unfinished buildings and the occasional flag-flying monument to the revolution. We passed through a village, its wide streets lined in the usual mélange of Soviet-era concrete and colorful, crumbling Spanish Colonial architecture. Suddenly, my eyes landed on one building that stood out from the rest, a burst of turquoise, red, and gold—more elaborate than anything else on the street. As the bus rattled past, I noticed the emblem carved in bold strokes above the front door: a square and compass, framed by a glorious golden starburst.

The sign immediately distinguished this as a Masonic lodge. Usually such places do little to announce their presence. In Western Europe, Masonic lodges tend to be more conservative affairs. They are grand buildings, very often, but discreet enough that their function doesn’t become apparent until you can make out their symbols and plaques. This Cuban lodge, on the other hand, was the most garish, colorful thing in town.

It was at that point I remembered I was traveling through a Communist state, and my brain did a somersault. Because as far as I knew, Freemasonry had been outlawed by virtually every Communist party of the 20th century. For example: The Grand Lodge of Yugoslavia was “put to sleep” from 1940 to 1990. In Bulgaria, Freemasonry was banned by the 1940 Law for the Defense of the Nation, and subsequently active and even past Freemasons were frequently accused of being agents of foreign intelligence services.

Freemasonry was outlawed in the Soviet Union, too, and while some of the leading Communist revolutionaries had been members of Masonic lodges, they denounced the craft after seizing power in Russia. The general consensus seemed to be that such a system was incompatible with the new mode of Marxist society. As I looked out the window of that humid, rattling bus, however, it seemed as though Cuba disagreed.

That roadside carnival of a lodge was no aberrancy, either, as I’d discover during the rest of my stay in Cuba. Now that my eyes were open, I began noticing them everywhere—collecting them, even. I spotted the Logia Luz del Sur and Logia Aurora del Bien in Trinidad, on the south coast of Cuba; Logia José Jacinto Milanés № 21 in Matanza; Logia Hermanos de la Guardia in Cifuentes; and Logia Asilo de la Virtud (the “asylum of virtue”) in Cienfuegos.

They dominated town squares; they burst in colorful formations of pillars and plaster facades from otherwise plain village streets. Far from outlawing Freemasonry, Cuba appeared to be celebrating it. So I decided to do some digging and find out why.

The fact is that Cuba is home to a flourishing Masonic community. In 2010, it was reported that the island had more than 300 Masonic lodges and more than 29,000 active members. The fraternity first appeared there in 1763 and grew as French Masons fled the Haitian Revolution of 1791.

The first part of this story is nothing peculiar. The former colonies of the Caribbean have long been a hotbed of Masonry. But the Grand Lodge of Cuba is remarkable in that it thrived under a Marxist-Leninist dictatorship. One of the popular (if unverified) theories for that is that Fidel Castro may have been a Mason.

When the revolutionaries landed on Cuba in 1956—the Castro brothers, Che Guevara, and the rest, all 82 of them squeezed onto a 12-berth yacht named Granma—the island was under the tyrannical rule of Fulgencio Batista. The story goes that Castro and his brother were hidden from Batista’s forces by a small Masonic lodge in the Sierra Maestra. It was from this remote lodge that Castro laid the foundation for his 26th of July Movement, which in 1959 would ultimately lead to the socialist revolution in Cuba.

Some say Castro himself was initiated as a Mason during that time. Others suggest that it was only Raúl Castro who joined, or some of the revolutionary fighters. Either way, the kindness and support allegedly given to Castro during those years by a remote Masonic community offered a popular theory for the tolerance Castro’s regime would later show toward Cuban Freemasonry.

It’s certainly a good story, although the truth might be simpler; after all, Cuba already owed a great debt to its Freemasons. During the island’s struggle for independence from Spain, many of Cuba’s leading revolutionaries were proud Masons, including Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, Antonia Maceo, and the famous poet, journalist, and philosopher José Martí. It would have been exceedingly difficult for the regime to separate the memory of Cuba’s national heroes from the ideas they had openly celebrated. “

Afro-Cuban faith and Freemasonry…both played a role in consensus-building after the revolution,” writes the folklorist E. C. Ballard. “The first was useful to gain support from the largely Afro- Cuban population of the island who remain poorly represented in the government. The second ensured the sympathy of the Latin American left.”

As a result, Freemasonry in Cuba remained legal, though it was monitored by the Office of Religious Affairs. Membership numbers rose after the fall of the Soviet Union and Castro’s government eased restrictions on the craft, allowing the opening of new lodges and even permitting Masons to participate in public ceremonies dressed in full regalia.

Some elements of Cuban Masonry are notable for their differences. In general, for instance, Masons’ dress code in Cuba tends to be fairly relaxed, and women are sometimes admitted to lodges. Ballard speculates that such adaptations are “welcomed generally in a society which formally eschews bias and discrimination of any kind.”

Today, more than a third of Cuba’s Freemasons are based in Havana, where the impressive Grand Lodge building dominates an entire city block, daubed in esoteric symbols. This is the nucleus of Cuban Freemasonry, the nerve center from which all 316 Cuban lodges are regulated; and after my week of road-tripping through the cities of the south, I was eager to pay it a visit.

Above:

Masonic lodges and monuments in Cuba are easy to spot—like the colorful Luz del Sur lodge. Photo by Darmon Richter.

Back in Havana, I spent a morning wandering the city’s main cemetery, Necrópolis Cristóbal Colón. Containing row upon row of polished marble, the necropolis was founded in 1876 by the Spanish. As I traversed the endless parade of bleached-white stone, I found a mass of esoteric epitaphs among the grave markers. Lodges gathered their dead together, wrought-iron fences separating the deceased into memorial plots according to Masonic custom. The symbols of the craft were easy to spot.

In the afternoon, I set out for the Grand Lodge of Cuba at 508 Avenida Salvador Allende, a towering 11-story structure that, before the appearance of a new wave of tourist hotels in the capital, was the second-tallest building on the island. (The avenue itself was named after the 30th president of Chile— a Marxist, Freemason, and good friend of Castro’s.)

I spotted the Gran Logia almost the moment I turned onto the avenue. I had cut through backstreets on my way there, under washing lines and spiderwebbed telephone cables, where children played baseball in the street. And then, suddenly, there it was. Pontiacs and Corvettes puttered up and down the avenue, while at the far end, rising clear of the colonial blocks and arches, a yellow titan broke the horizon. It was every bit as subtle as the village lodges I’d seen, 11 floors of budget Art Deco capped off with a globe, a square, and a compass.

Established in 1955, Havana’s Masonic headquarters contain the office of the grand secretary, a museum, a home for elderly Masons, and an extensive library (though, according to rumor, the Cuban government has since commandeered most of the floors for its own use). I got close—close enough to admire the zodiac clock set into the building’s facade—but despite my best efforts, I couldn’t get inside.

A gentleman in suit and glasses stood between the doors and greeted me with a quizzical smile. I’d been told the library was open to layfolk. I gestured past him, toward the interior of the building, and said “¿Por favor?” while flashing the best smile I could manage. I was answered with a motion of genteel refusal.

Not wanting an argument, I stepped away, only to run into a man who’d been watching the entire affair. The man was 60 perhaps, with a sun-weathered face and the wiry body of a farmworker. I’d noticed him as I arrived in the park, raking leaves while puffing on a cigar. “Hector,” he said with a mischievous smile, and shook my hand.

We exchanged pleasantries, and then I decided to swing for the fences. Was Fidel Castro a Freemason? I asked him. He laughed.

“Perhaps,” he said, blowing a cloud of smoke. “Who knows?”

“Hector,” I said, “are you a Mason?”

Hector puffed thoughtfully on his cigar for a moment, his head half lost in the clouds. “If I am not, I would tell you no,” he replied. “But if I am, I would also tell you no.” Then he laughed enigmatically, and I decided to leave it at that.

Note: Excerpted from the author’s original article.

Above:

The towering Grand Lodge of Cuba dominates the Avenida Salvador Allende in Cuba. Photo by Alamy.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Darmon Richter

Alamy

As the Masonic youth order Rainbow Girls celebrates its centennial, a look back on all that’s changed, and all that hasn’t.

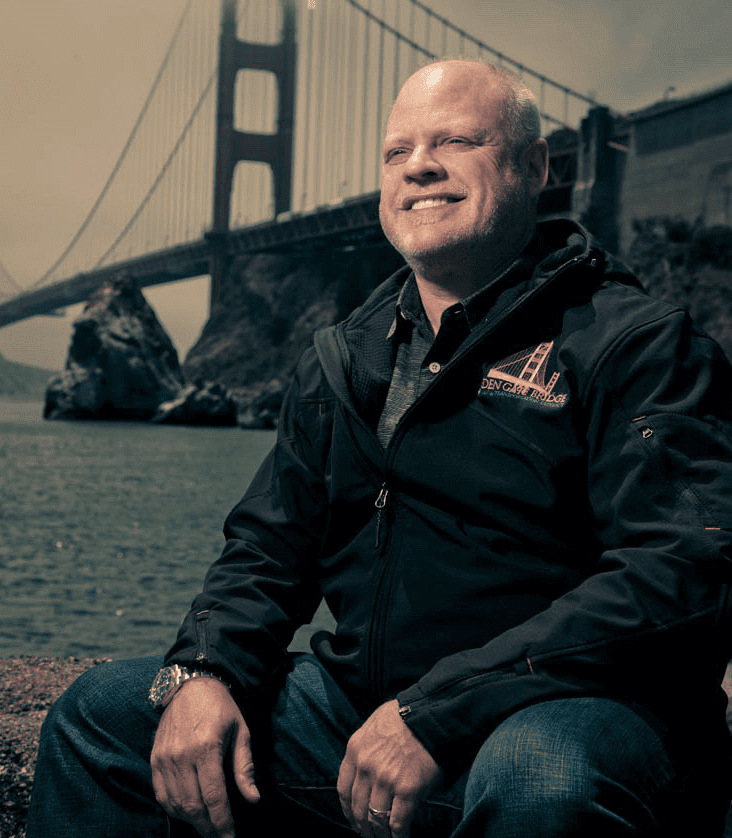

A bridge-building Bay Area Mason reflects on the importance of charity, giving back, and offering Masonic relief.

A history-spanning, forward-looking celebration of the fraternal and cultural connections between California and Mexican Freemasonry.