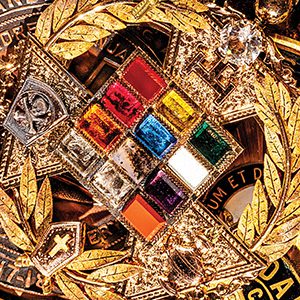

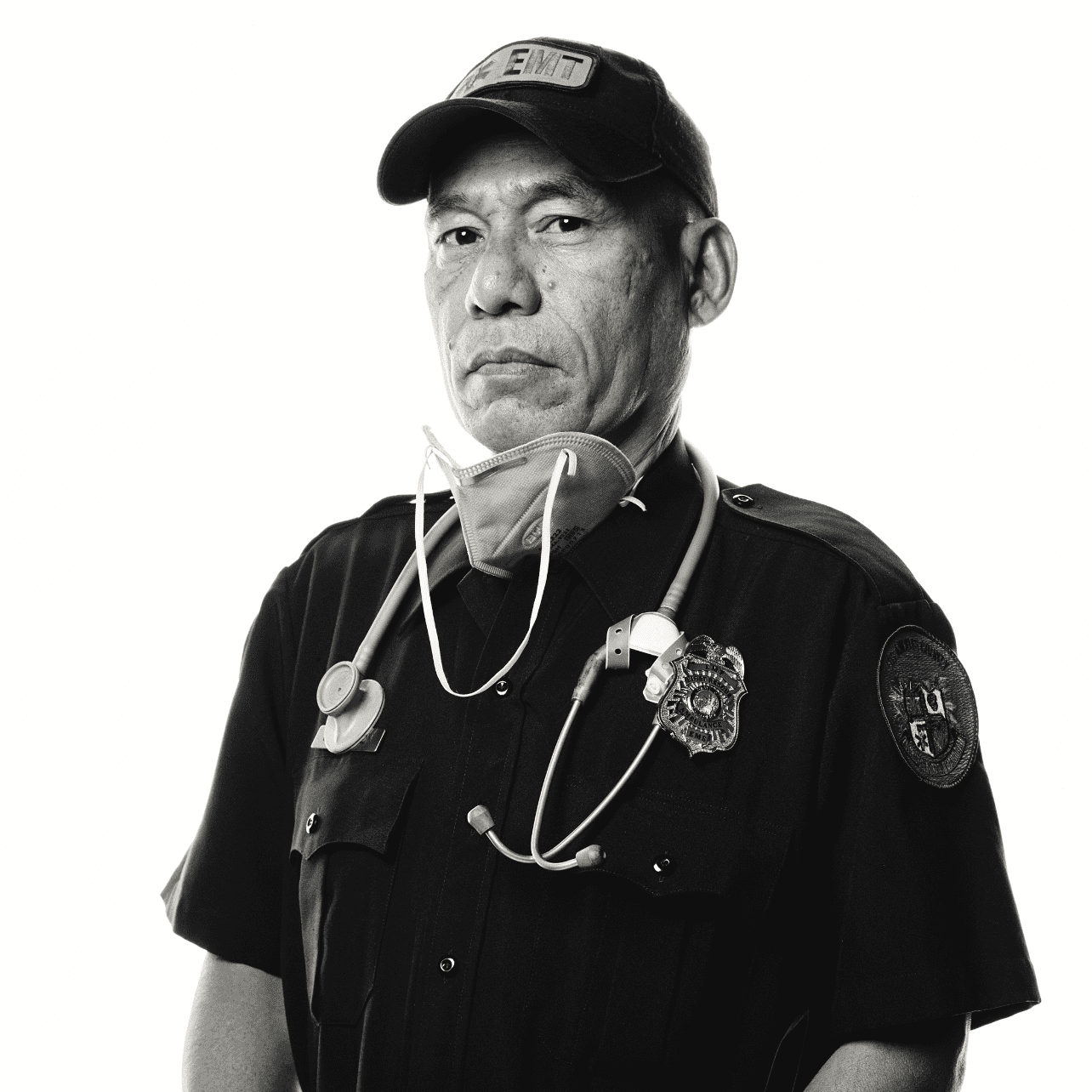

For Masonic Artifact Collectors, They’re Another Man’s Treasure

To some, collecting Masonic artifacts, rings, aprons, and jewelry isn’t just a hobby. It’s a craze.

Aquatic Park is one of the most picturesque vistas in all of San Francisco, a city of postcard views. A tiny, sandy cove ringed by Ghirardelli Square, Beach Street, and the historic Hyde Street Pier, the park is one of the most reliably sunny spots in town. Most weekend days, you’ll see a stream of swimmers, kayakers, and rowers pulling their way across its protected waters. Beyond them, sailboats navigate the choppy bay against the backdrop of the majestic Golden Gate Bridge.

But the charming, jewel box scene belies a more lurid chapter of the city’s history. It’s invisible to all but the most carefully trained eye. Yet clues of the city’s distant past are there in the seemingly mismatched stones that form the sweeping breakwater.

It wasn’t long ago that names could still be read on these stones. But with each wave that laps the seawall, the memory of how the municipal pier was born—as well as many other of the city’s large urban projects of the early 20th century—is further erased. These are the tombstones of Aquatic Park, dug up by workers clearing the city’s cemeteries a century ago and unceremoniously deposited around San Francisco.

They aren’t the only ones. Grave markers can be spotted by the jetty at the Golden Gate Yacht Club, at Ocean Beach, and at the base of the Golden Gate Bridge. Even a walking path in Buena Vista Park is lined with old tombstones, some still visible today. During major building renovations, Gold Rush–era caskets were found beneath the Asian Art Museum, the Legion of Honor, and countless private homes. The city is practically brimming with these morbid reminders from yesteryear.

Like so many other aspects of California history, Freemasonry plays a key role in the story.

At the turn of the last century, San Francisco was a city practically full of cemeteries—by one count, as many as 30 within the city’s seven-by-seven-mile square. There were graveyards for deceased Chinese, French, German, Italian, Greek, Native American, Japanese, Scottish, and Scandinavian people. There were cemeteries for Jewish, Catholic, and Chinese Christian parishioners, among many others. There were plots for orphans, seamen, firefighters, and members of the typographical union. But perhaps the most elaborate of them all was the 38-acre Masonic Cemetery on Lone Mountain.

The land for the Masonic Cemetery was purchased in 1854 on what is now the University of San Francisco’s grounds. It opened a decade later, eventually serving nearly 20,000 souls. Together with the nearby Odd Fellows Cemetery, Calvary Cemetery, and Laurel Hill Cemetery, they made up the “big four” graveyards of Lone Mountain.

Built at the height of the so-called “beautification of death” movement, which ushered in a much more theatrical approach to mortuary work, like ornate casket furnishings and elaborate monuments to the deceased, the Masonic was by some estimations the finest of them all. The San Francisco Morning Call newspaper in 1887 described it as “elaborately beautified in floral design, and contain[ing] many handsome monuments.”

The entrance to the park was marked by a large castellated tomb; other decorations included a white marble obelisk topped by a statue of Grief, and monuments to preeminent San Francisco Masons including the sugar magnate Adolph B. Spreckles and Munroe Ashbury, an early champion of Golden Gate Park and the namesake of Ashbury Street (of the famous Haight-Ashbury district). Other notable figures buried there included Etienne Guittard, the famous French-born chocolatier; Jacob Neff, the Gold Rush mining kingpin elected lieutenant governor in 1899; and the city’s most beloved eccentric, Emperor Norton I, a charter member of Occidental Lodge № 22.

An 1880s tourist guidebook went so far as to recommend the cemetery for sightseeing: “The broad, serpentine walks, the fountain playing in the center, the profusion of flowers, and the large number of handsome monuments make it well worth a visit.”

However, space for the dead began to interfere with space for the living in the growing city. So in 1901, mayor James Phelan banned any new burials or cremations within city limits, kicking off what would become a multi-decade campaign to eradicate the city’s profusion of graveyards.

Families of the deceased, incensed by the apparent sacrilege, did not give in without a fight. However, several factors worked against them. First was the urgent need for new housing in the cramped city. Second was a change in tastes, as the Victorian-era “garden-park cemeteries” like the Masonic began falling out of fashion. But perhaps most important was the 1906 earthquake, which badly damaged the city’s many cemeteries, including the Masonic. In the aftermath, the crumbling graveyards were seen as public eyesores and a threat to public health.

Heated litigation over the forced removal stretched on for years, ultimately reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. But major rulings in 1914 and then 1924 sealed the fate of most of San Francisco’s cemeteries. Seeing the writing on the wall, the San Francisco Masonic Cemetery Association, which managed the site, began negotiating a sale to St. Ignatius College, now the University of San Francisco.

Above:

The breakwater at Aquatic Park Cove, in San Francisco, is made up of discarded headstones taken from the city’s 19th century cemeteries. NPS/Alamy

The final death knell came in 1930, when the city officially rezoned the area of Lone Mountain, which formally allowed the boards of the big four cemeteries to sell off their land and reinter their dead elsewhere. As the moves began, one cemetery at a time, caskets were dug up and transported south to the sleepy town of Lawndale, now known as Colma, the so-called “city of souls.” Today, Colma is home to 18 cemeteries. Nearly 1.5 million people are buried there, 1,000 times its living population.

With the cemetery’s closure imminent, the San Francisco Masonic Cemetery Association raised funds to purchase land for a new resting place in Colma called Woodlawn Memorial Park. (In 1996, Woodlawn was sold to a private corporation, but remains the largest de facto Masonic cemetery in the Bay Area.) Most of the bodies originally buried at the San Francisco site were dug up and transported to Woodlawn, though a few wound up at nearby cemeteries including Olivet Memorial Park, Cypress Lawn, and Greenlawn Memorial Park just a few blocks away.

Many, however, were never removed at all—an exceedingly common occurrence citywide during the great reinterrment period. One study found that at Golden Gate Cemetery (now the site of the Legion of Honor and the Lincoln Park Golf Course), only about 1,000 bodies’ remains were ever actually removed, leaving an estimated 18,000 still in the ground. (A museum excavation in 1993 uncovered 800 of them.)

At the four Lone Mountain cemeteries, the herculean task of digging up the deceased was, understandably, challenging. One report described it as “chaotic and hasty.” While many caskets could be moved intact, others were in various states of decomposition, and only some of the remains were moved. Others were left “wholly untouched,” according to a 2011 archaeological survey conducted on behalf of the University of San Francisco.

In the end, relatively few of the deceased were ever provided with new individual grave markers. Of the 20,000 people buried at the Masonic Cemetery, about 5,000 remains were claimed by family members and reinterred in Colma, according to a fraternity report at the time. The rest—up to 15,000—were, like the rest of the city’s unclaimed, placed in mass graves, their tombstones left behind. Even Masonic dignitaries met that fate: Among those moved to an unmarked grave in the common plot was Jonathan Stevenson, the first grand master of California. It wasn’t until 1954 that he was reinterred in the California № 1 lodge plot at Cypress Lawn and a memorial plaque was erected in his memory.

Above:

A postcard lithograph from the late 1800s, depicting the Masonic Cemetery bounded by Masonic and Parker avenues and Turk and Fulton streets. Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

“The place of public history is vulnerable to the advance of urban progress,” wrote historian Tamara Venit-Shelton of the mass reburial efforts in the Journal of California History. There could hardly be a more apt visual metaphor than in the thousands of deserted tombstones left behind in the mass exhumation and reinterment of San Francisco’s dead. Families of the deceased were instructed to claim the headstones themselves, but few ever did. Eventually, workers from the city’s Department of Public Works collected the thousands of marble and granite stones for use as building materials. According to Shelton, those stones were used in construction projects all over the city, including the breakwaters at Aquatic Park and the municipal yacht harbor, and for paving roads in the North Beach neighborhood.

There are no records of which headstones were sent where. And with the passing of time, their markings have become harder and harder to decipher. But for many old-time members of the city’s rowing clubs, which use Aquatic Park as their headquarters, it was only a generation ago that swimmers passing close to the seawall could make out the names of the departed carved into the odd bit of rock. Perhaps in some protected nook or cranny, a Masonic square and compass survives.

It can be hard to reconcile the seemingly pitiless exhumation of the city’s deceased with the supposed finality of a casket laid to rest. But an appropriate metaphor can be drawn from Masonry, which teaches members that their work aims to build a temple in spirit. Even the grandest temple of stone can be destroyed, but no material is as long-lasting as memory.

So while the stones memorializing the Masons buried at Lone Mountain have long since vanished or been eroded by time and tide, their story lives on in other ways. The loveliness of Aquatic Park, protected from the harsh San Francisco Bay by the breakwater, certainly suggests as much. At Lone Mountain, their memory lives on, hiding in plain sight to every person who passes the old site as they walk or drive along what’s now known as Masonic Avenue.

Tony Gilbert is a writer and member of Golden Gate Speranza № 30, as well as a past board member of the South End Rowing Club. Ian A. Stewart is a writer and editor of California Freemason.

Above:

Ruined headstones at the former Masonic Cemetery in San Francisco in the wake of the 1906 earthquake.

TOP ILLUSTRATION BY

Anthony Freda

To some, collecting Masonic artifacts, rings, aprons, and jewelry isn’t just a hobby. It’s a craze.

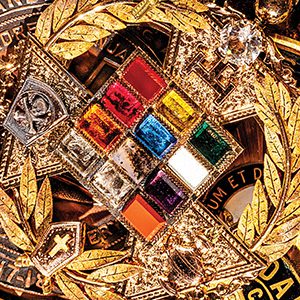

Freemasonry offers a framework to living a better life. That’s why it holds so many lessons for confronting death—and whatever comes next.

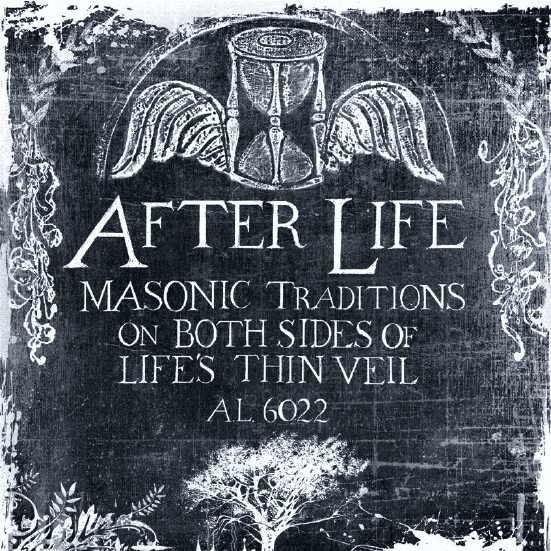

Meet three Masons with an intimate familiarity with death—and the other side.