HISTORY

Tales From a Masonic Pen

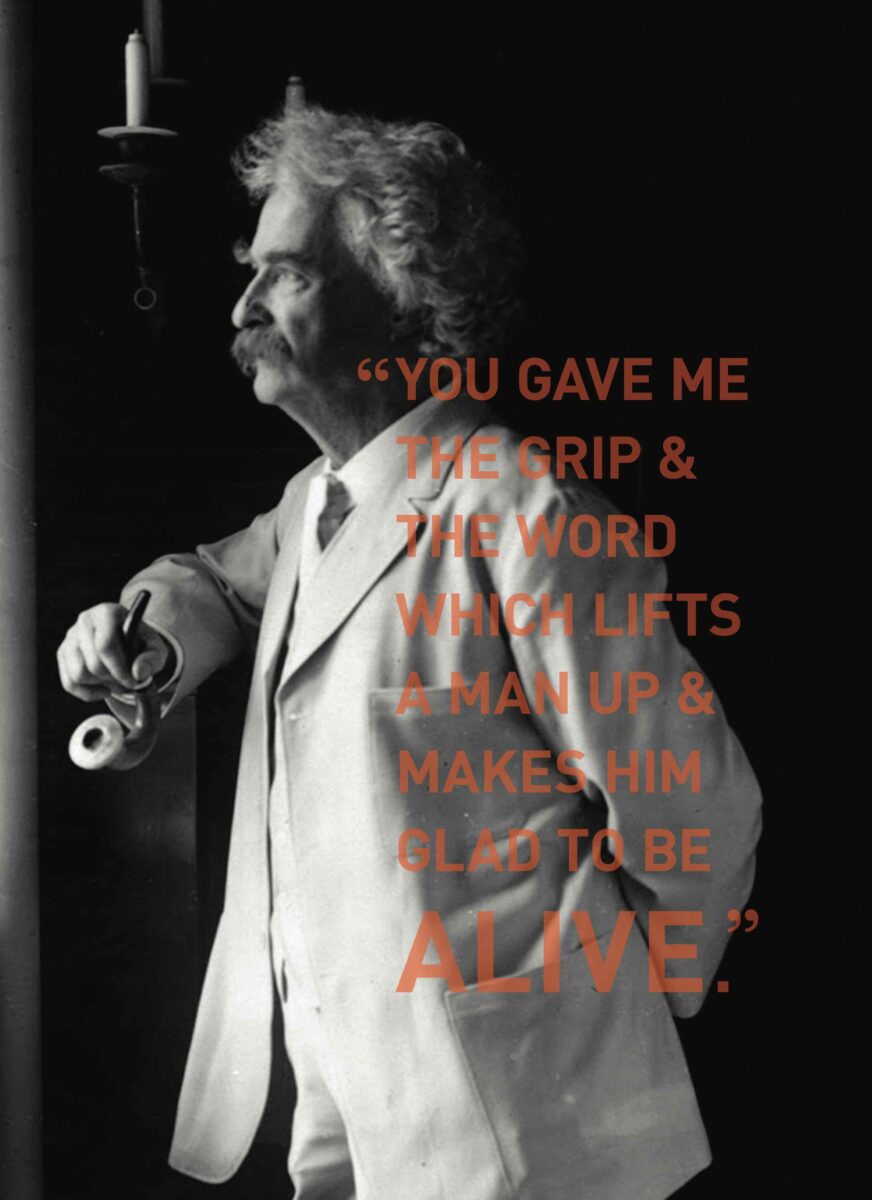

Discovering the fraternal Life of Mark Twain

By Heather Boerner

Below is the article from the December/January 2013 issue of California Freemason. Read the full issue here.

Mark Twain – born Samuel Langhorne Clemens – was the trickster storyteller of American letters, so it should be no surprise that he applied his particular brand of observation to the Masonry as well. Take, for instance, his description of a character in his 1897 “Tom Sawyer’s Conspiracy”:

“[H]e was Inside Sentinel of the Masons, and Outside Sentinel of the Odd Fellows, and a kind a head bung-starter or something of the Foes of the Flowing Bowl, and something or other to the Daughters of Rebecca, and something like it to the King’s Daughters, and Royal Grand Warden to the Knights of Morality, and Sublime Grand Marshal of the Good Templars, and there warn’t no fancy apron agoing but he had a sample, and no turnout but he was in the procession, with his banner or his sword, or toting a bible on a tray, and looking awful serious and responsible, and yet not getting a cent. A good man, he was, they don’t make no better.”

The idea of the 19th century man as a brother to many and a joiner of multiple fraternal organizations is not based on Twain’s own life. A Mason for a scant eight years – less, if you include a period in which his dues went unpaid – there is nonetheless evidence that the craft had an indelible influence on Twain.

Twain was born in 1835 in Missouri. The death of his father and his natural intellect sent him to work before his teens as a newspaper typesetter. Shortly thereafter, he was a columnist at his brother’s newspaper where he later became assistant editor and, when his brother was out of town, boldly whipped up a feud with another local paper.

Twain was born in 1835 in Missouri. The death of his father and his natural intellect sent him to work before his teens as a newspaper typesetter. Shortly thereafter, he was a columnist at his brother’s newspaper where he later became assistant editor and, when his brother was out of town, boldly whipped up a feud with another local paper.

Twain found homes throughout the United States, from St. Louis to New York, Philadelphia, small-town Iowa, and New Orleans. He worked many years as a newspaperman and typesetter before taking up the unlikely vocation of river pilot. Eventually, he’d also work as a miner, serve briefly in the Confederate Army, tour the Hawaiian Islands, and live abroad.

By the time Twain became an Entered Apprentice at Polar Star Lodge No. 79 in St. Louis, he’d already published his first story, “The Dandy Frightening the Squatter.” But just after he was raised to Master Mason in July 1861, he left Missouri and his lodge to join his brother in Nevada. Not long after, he continued his journalism career, working as the editor for a Nevada newspaper, as well as several others, sometimes under his own name and other times favoring pseudonyms. During his travels, Twain stopped paying his lodge dues and his Masonic membership was suspended.

But his association with Masonry was not at its end. In February 1865, Twain served as senior deacon at Bear Mountain Lodge No. 75 in California’s Gold Country.

Later that year, he published his first well-received short story, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” Using the keen observation of a journalist and the humor of a fiction writer, Twain soon found himself writing travelogues of his trips to Europe and around the West for magazines in New York, some of which were turned into books. Lecture tours followed.

Unfortunately, as Twain’s career blossomed, his participation in the fraternity waned. He demitted in 1869. But it appears that Masonry still remained on his mind.

In 1868, Twain traveled to Jerusalem and cut a branch from a cedar tree just outside the city walls. He had it made into a gavel, which he sent back to his lodge in St. Louis with this uncharacteristically serious note: “This mallet is a cedar, cut in the forest of Lebanon, whence Solomon obtained the timbers for the Temple.”

The following decade, Twain’s most famous works were published. “The Prince and The Pauper”; the “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”; and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” By this time, he’d been long married, and had a family.

In his later years, however, Twain had a run of bad luck. Bad investments left him struggling financially. His publishing house went under. His wife, Livy, and daughters, Susy and Jean, passed away. Twain’s mood, perhaps understandably, darkened – a change that was clearly reflected in his autobiographical writing.

And yet, in these moments of despair, Twain seemed to find solace in the concepts of Masonry. In 1900 – a decade before his death and many years after he demitted – Twain stood before the New York City Lotos Club, a club for writers of which Twain was a member, and spoke of the pain that had befallen him and the world.

“Seven years ago when I was old and worn and down, you gave me the grip and the word which lifts a man up and makes him glad to be alive,” he told the group. “I come back from my exile fresh and young and alive, ready to begin anew.”

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS:

Courtesy of Henry W. Coil Library & Museum of Freemasonry