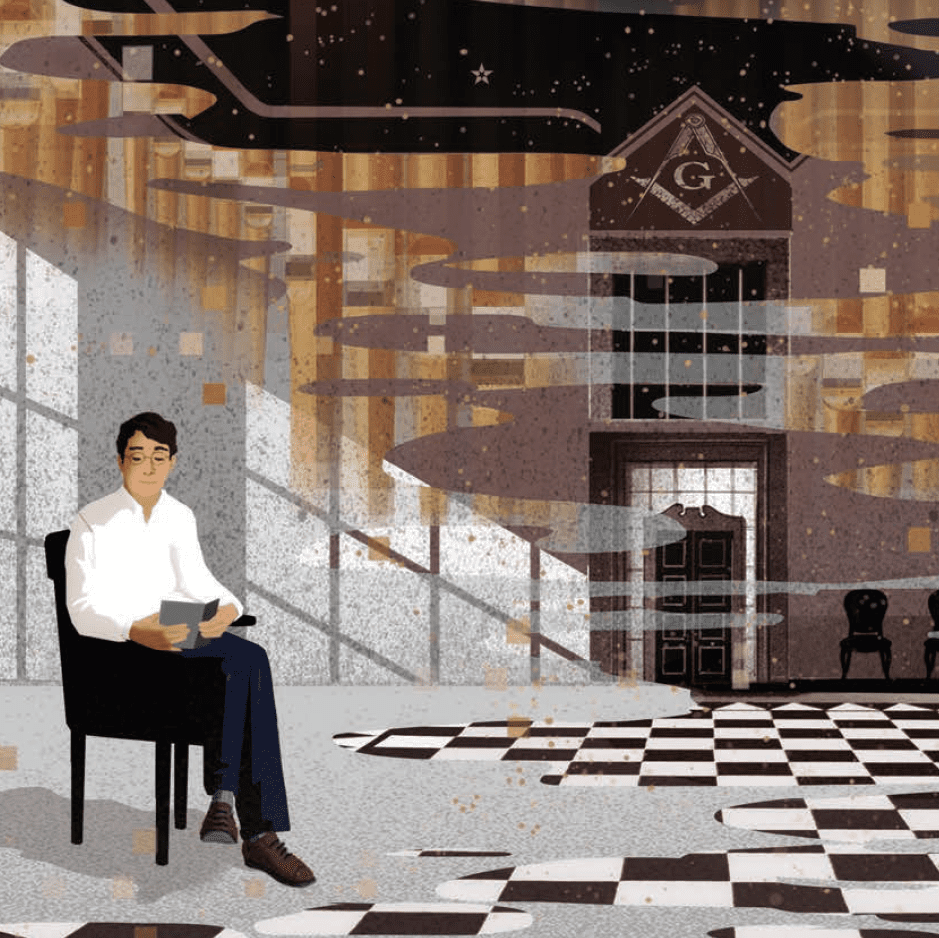

Executive Message: Sounds of Harmony

Grand Master Jeffery Wilkins explains how music deepens the magic of Masonry.

Photos by Willy Branlund. Text by Ian A. Stewart

There are your simple repairs, of course— cracks in the body, a broken bridge. But what Juan Soto really loves is a full-on violin restoration job. As a luthier, or string-instrument restorer, he says the best part of his job is taking a dusty old instrument—usually a violin, viola, or cello—that has been sitting in an attic for decades, pulling it apart, and then slowly and lovingly putting it back together again. “We don’t make much money on it, but I love to do those jobs,” Soto says. “It’s fulfilling to bring something to life and then see it again in a performance.”

Growing up in Guatemala City, Soto didn’t get his start as a musical protégé. Rather, he began as a carpenter and furniture maker. Years later, after moving to Los Angeles, he found work in a violin repair shop because of his ability to match varnishes—a key part of instrument restoration. In 2012, he pulled up stakes and moved to Las Vegas, where he now runs his own shop. In recent years, he’s become a specialist in mariachi instruments including the guitar, guitarrón, and vihuela.

Moving to the desert hasn’t stopped Soto from maintaining a connection to California Masonry. He is a past master of the former Tujunga Lodge No. 592, where he was given the Hiram Award, as well as a longtime inspector for District No. 533. In 2006, he helped lead a merger with Panamericana Lodge No. 513, which became just the second Spanish-language lodge in Southern California. He remains a candidate coach there and a member of the advisory committee, as well as an affiliate of Las Vegas’s Mount Moriah No. 39.

Moving to the desert hasn’t stopped Soto from maintaining a connection to California Masonry. He is a past master of the former Tujunga Lodge No. 592, where he was given the Hiram Award, as well as a longtime inspector for District No. 533. In 2006, he helped lead a merger with Panamericana Lodge No. 513, which became just the second Spanish-language lodge in Southern California. He remains a candidate coach there and a member of the advisory committee, as well as an affiliate of Las Vegas’s Mount Moriah No. 39.

As a master craftsman, Soto says that he appreciates the symbolism of the Masonic working tools. “Masonry helps you develop perseverance and patience,” he says. “That’s something you definitely need to do the work I do.”

When it came time to get serious about pursuing a career in the music business, Rafael Barajas was pragmatic. “I live in L.A.,” he says. “If you throw a rock anywhere, you’ll hit a guitarist. Maybe a better choice for me is to work on all those guitars.”

So it was that Barajas set out on a successful career as a custom guitar builder. Today he’s both the lead builder for Yamaha Guitar Development and owner of Barajas Custom Guitars, where he’s supplied instruments for axmen associated with several prominent acts, from J. Balvin and Jennifer Lopez to Julio Iglesias and the Smashing Pumpkins.

So it was that Barajas set out on a successful career as a custom guitar builder. Today he’s both the lead builder for Yamaha Guitar Development and owner of Barajas Custom Guitars, where he’s supplied instruments for axmen associated with several prominent acts, from J. Balvin and Jennifer Lopez to Julio Iglesias and the Smashing Pumpkins.

Building top-flight electric guitars requires a range of skills, making Barajas a rarity as a one-man shop. “Usually, guys specialize in something specific, like paint or electronic work,” he says. “But I do my own paint, I can work the [computer numerical control] machine and pin routers, wire the electronics, everything.” Then there are the soft skills, like working with temperamental artists and handling the marketing.

It’s in that last capacity, he says, that he’s benefitted from his membership in Freemasonry. Barajas’s grandfather, Gilberto Gamboa, was a member in Tijuana, where Barajas was raised. But it was an uncle in San Diego who inspired him to join Home No. 721. “Honestly, it was a way to make some new friends,” he says. “I knew that when you meet a Mason, you know he’s a good guy, you can trust him.”

It’s in that last capacity, he says, that he’s benefitted from his membership in Freemasonry. Barajas’s grandfather, Gilberto Gamboa, was a member in Tijuana, where Barajas was raised. But it was an uncle in San Diego who inspired him to join Home No. 721. “Honestly, it was a way to make some new friends,” he says. “I knew that when you meet a Mason, you know he’s a good guy, you can trust him.”

Occasionally, his two worlds overlap. Barajas recalls a recent conversation he had with the guitarist Michael Herring (stage name Fish), who has toured with the likes of Christina Aguilera and Prince. “He was at the shop, and he asked me who had the Masonic symbol on their car. I was like, That’s me,” Barajas says. “And he said, Wow, I just did my Fellow Craft degree at Burbank No. 406. So I told him when he has his Master Mason degree, I’ll be there. I guess we became a little more than friends that day.”

It might seem like transitioning from the role of corporate executive to that of a piano tuner would represent a total U-turn. But for Robert Casper, a past master of Gateway No. 339, the late-career switch wasn’t as out-of-left-field as it looks. “I was always pretty handy and interested in mechanical things, so that came pretty naturally to me,” he says.

Still, it was a considerable change for Casper, who’d owned an electronics manufacturing firm for years before getting into piano repairs. But approaching retirement, he figured he needed a new pastime—and piano tuning spoke to him. As his wife is a children’s piano instructor, he already had a built-in clientele.

Still, it was a considerable change for Casper, who’d owned an electronics manufacturing firm for years before getting into piano repairs. But approaching retirement, he figured he needed a new pastime—and piano tuning spoke to him. As his wife is a children’s piano instructor, he already had a built-in clientele.

So Casper immersed himself in piano tuning and repair courses and programs to learn the trade. He even joined the local piano-tuning guild—a sort of Masonic lodge for those in the trade. “We meet once a month and share our experiences and tricks and tools,” he says. “It’s a very sharing, helping group.”

With that support, Casper learned enough to tune, repair, and rebuild about every kind of piano there is—even some that aren’t technically pianos. Twice now, Casper has been asked to rebuild a harpsichord, the instrument’s diminutive, Bach-era predecessor, which uses internal picks rather than hammers to make its signature sound. “That was harder because I didn’t have any mentors. I had to do a lot of learning in different ways,” he says. Of the two instrunents, “I ended up buying both, and sold the first one to a movie studio.”

Somewhat more familiar, he’s rebuilt antique grand pianos from the 19th century manufacturers Chickering and Sons and Wm. Knabe & Co., instruments that can fetch more than $30,000 once restored. Not bad for a second career.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Willy Branlund

Grand Master Jeffery Wilkins explains how music deepens the magic of Masonry.

Why two grand lodge officers are on a quest to bring music into every Masonic lodge.