Lodge Profile: Looking Up at Morning Star No. 19

Things are looking up for Stockton’s Morning Star Masonic Lodge No. 19.

By Ian A. Stewart

When Bob Sachs first peered inside the vault in the basement of his lodge hall, he wasn’t totally sure what he was looking at. But he did know who he was looking at: There, wrapped in canvas, was a five-foot-tall oil painting of George Washington dressed in a Masonic apron.

It’s the kind of discovery that fans of Antiques Roadshow live for. For Sachs, a past master of King David’s Lodge No. 209 in San Luis Obispo, it was the beginning of what is now practically a full-time hobby. “I’ve become like a dog with a bone,” Sachs says with a laugh.

It’s a common story. In 2018, workers at the California Masonic Memorial Temple discovered a series of officer portraits and a quite-valuable antique lithograph of King Solomon’s temple in a crawl space. Appraisers determined that the paintings were made by D. T. Blakiston, an important 19th-century San Francisco artist. The lithograph was credited to John Senex, the 18th-century engraver of the frontispiece of James Anderson’s Constitutions of the Free-Masons.

For Sachs, the Washington painting—dated 1870, the year King David’s was founded—represented a window into the past. He asked an old friend, Jim Moore, a former director of the Albuquerque Museum of Art, to come see the piece. Moore recognized the inscription of Léon Trousset, a French-born painter of the American Southwest. Moore told Sachs that the painting was historically significant, though physically it was in bad shape. He began to research the painter and prepare notes.

Above:

Under ultraviolet lights, hidden imperfections are made visible in an antique portrait of George Washington belonging to King David’s Lodge No. 209.

Never a household name, Trousset nevertheless carved out a successful career as an itinerant painter in the late 19th century, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Jules Tavernier, founder of the Bohemian Club. Trousset moved often, painting views of California, Mexico, and Texas. His works are kept in several collections today, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Trousset’s style is his personal mixture of naïve and romantic,” wrote art historian Frederick Kluck.

The artist’s identity wasn’t the only interesting thing Sachs learned. Representatives at the George Washington Masonic Memorial in Virginia explained that very few original images of Washington in Masonic regalia exist, and urged him to have the painting professionally restored.

As ubiquitous as Washington’s image is today, they explained, few paintings of him were made during his lifetime. Most pictures of Washington are facsimiles of Gilbert Stuart’s famous Landsdowne portrait, the basis for his image on the dollar bill. That rendering was subsequently engraved, copied, and distributed hundreds of times. Sometimes it was embellished, as on the 19th-century engraving by A.B. Walter entitled Washington as a Mason, which gave him a Masonic collar, jewel, and apron.

Curiously, the San Luis Obispo painting appeared not to draw from any single direct source. And what of the apron? Moore speculated that its design might have local roots—perhaps it was modeled by an original member of the lodge. “If that could be determined, then this painting would carry yet another level of meaning,” Moore wrote.

Meanwhile, other lodge members pitched in. Past master Dave Chesebro was able to connect with descendents of Trousset’s, while another lodge member recalled finding a contract for the painting for $178, an extraordinary amount at the time. The bill was signed by Walter Murray, the first master of the lodge, whose brother Alexander owned a locally famous tavern.

Above:

Art restorer Scott Haskins carefully retouches the Washington portrait.

From those facts, combined with biographical details of Trousset’s life, a picture began to emerge of the painting’s origin. An article on Trousset by art historian Roy B. Brown in 2006 noted the artist’s affinity for hanging out in local taverns. “Since bars, saloons, and cantinas have always been popular places for people to congregate and dispose of their excess cash, it is not surprising that León Trousset saw them as fitting venues to sell his paintings,” Brown wrote.

Moore and Sachs reasoned that Trousset might have met Murray in his brother’s bar. There, they guessed, he’d offered or been asked to make a portrait of America’s most famous Mason.

With that basic sketch of the painting’s provenance, Sachs brought the matter up for a vote: Would the lodge be willing to pay to have it professionally restored? Resoundingly, members said yes. “The painting might not have as much value as we’re putting into it, but it was a gift to the fraternity, and it’s our job to keep it and take care of it,” Chesebro says.

So last fall, Sachs and past master Peter Champion carefully drove the painting to the laboratory of Scott Haskins, an art restorer in Santa Barbara. Haskins examined the painting and determined that it was in need of a cleaning to stop deteriorating. The work had also been torn near the bottom and was fraying at the edges. “All those things create a number of problems,” he says.

Not insurmountable problems, though: Haskins placed new lining on the back of the painting, undid an earlier botched repair job, and, under a microscope, fused the torn fibers of the canvas back together. Using chemical solvents, he was able to bring the original colors back to life. “This is a super important historical painting,” Haskins says. “It’s part of our national history.”

As he puts the final touches on the painting, the lodge is preparing to welcome it home. A ceremony is planned for September that will include its unveiling along with talks by Haskins, representatives of the Trousset estate, and Washington Masonic Memorial president Mark Taggert.

And while the book may be closed on this mystery, it’s not quite the end of Sachs’s quest. “There are nooks and crannies in our lodge that people haven’t looked at in years,” he says. “There’s supposed to be a Bible signed by William McKinley, but no one can find it. So it’s time to start digging around.”

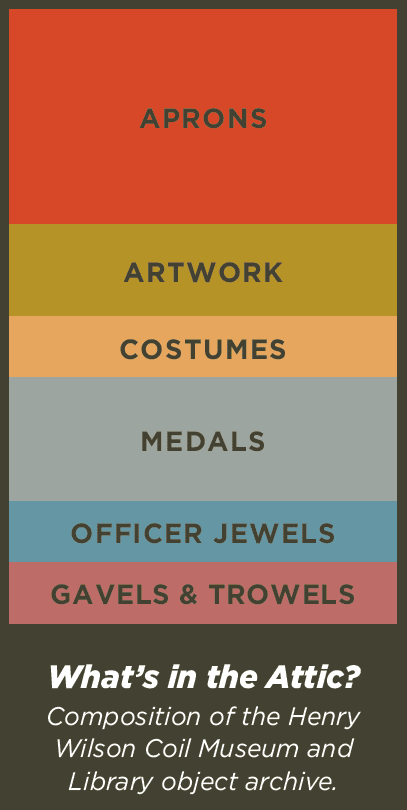

For many lodges, decades’ worth of paraphernalia can overwhelm even the most orderly secretary. Here, Joe Evans, collections manager for the Henry Wilson Coil Museum and Library, offers tips for managing your lodge’s material history.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Matthew Scott

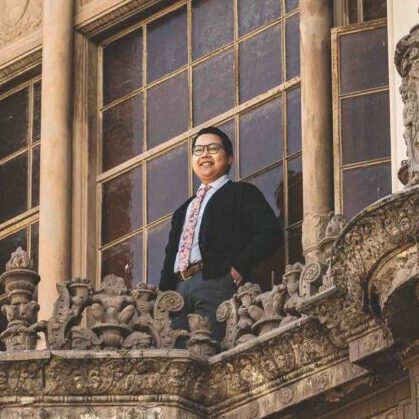

Things are looking up for Stockton’s Morning Star Masonic Lodge No. 19.

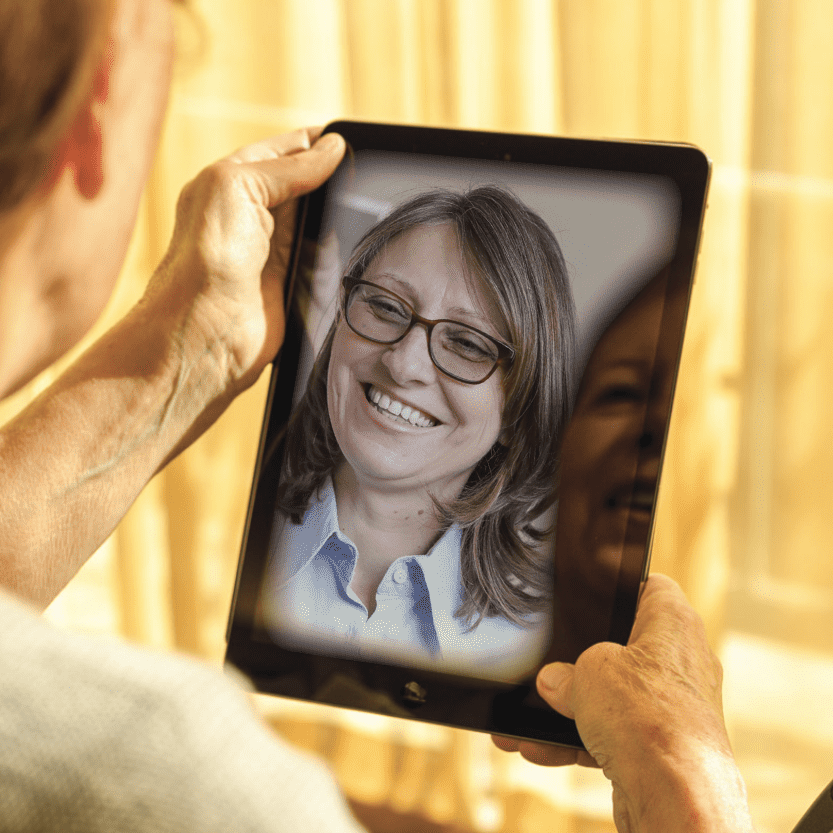

During the pandemic, MYCAF provided seniors at the Masonic Homes with vital connections.