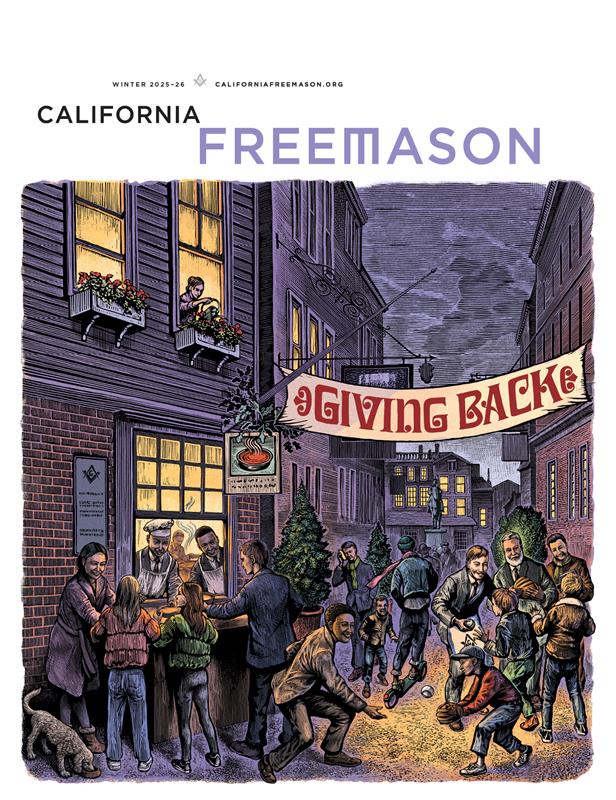

Cover Story

At Refreshment

Raising a glass to an important, if unofficial, Masonic custom.

By Brock Keeling

“You can say my Masonic career started over a beer,” begins Arthur Weiss, a fifth generation Freemason and the current grand master of the Grand Lodge of California. He’s recalling the first serious conversation he ever had about joining the fraternity. It was during a business trip to Louisiana, at a Ramada Inn hotel bar, that he learned about the community that would soon become a major part of his life. Weiss and two colleagues, both Masons, had just finished work for the day and sat down for a drink before dinner. “That’s when I decided to probe them for details about Freemasonry,” Weiss says. Other Masons have a similar story: Matthew McColm, a past master of Novus Veteris No. 864, met his two closest lodge friends over gin and tonics. And Justin Daza-Ritchie, a member of Liberal Arts No. 677, decided 20 years ago that he’d be a member for life while drinking martinis at the House of Prime Rib during the Annual Communication weekend in San Francisco.

For many, the most cherished parts of Masonry exist outside the formal boundaries of the craft— and often over a drink. Indeed, once lodge meetings are adjourned, a familiar custom ensues: Glasses clink. Mirth swells. The lodge is “at refreshment.”

That state encapsulates much of what Freemasonry is about: fraternity, camaraderie, and friendship, all of which point back to the core Masonic tenet of brotherly love. After a year during which that kind of close, interpersonal connection was sorely missed, it’s a reminder that Masonry is more than just monthly meetings and ritual practice. It’s raising a glass with a lifelong friend—or making a brand-new one. If the lodge room is where the connections of Freemasonry are formed, it’s often at the “afters” that those bonds are cemented.

That’s certainly been the case for McColm, a nine-year member of San Diego–based Novus Veteris Lodge No. 864. “Being at refreshment really goes beyond the walls of the lodge,” McColm says. Together with Mark Nielsen and Chris Radcliffe—the “three musketeers,” as they call themselves—the trio greet the at-refreshment hour with a customary G-and-T, a nod to Masonry’s British roots. Theirs is a friendship that extends beyond the lodge. “These are the guys I talked to before I proposed to my girlfriend,” he says. “It’s a special experience as an adult to find people you can relate to and forge a deep personal friendship with.”

Says Daza-Ritchie, “It’s a great way to be in a non-ritualized, non-stuffy setting with your fellow lodge members. It helped pull me into Masonry’s particular brand of friendship.”

In a million different ways, Masons and lodges develop their own unique cultures while at refreshment. More often than not, that involves hoisting a drink. And while drinking is not in any official way part of Freemasonry—and the craft explicitly prohibits it in many instances—it’s become an important tradition for many and a way to deepen the already strong ties between members.

From uncorking a fine bottle of wine at a black tie gala to downing a shot and a beer at the watering hole around the corner, Masonic refreshment takes many forms. For Peter Ackeret, it means heading over to Monk’s Cellar, a restaurant near Aquila Lodge No. 865 in Roseville, outside Sacramento. During pre-COVID times, Ackeret and his lodge brothers would decamp there after lodge meetings to break bread and offer toasts. At Saddleback- Laguna No. 672, members formed an unofficial club called Low 12 (a cheeky riff on High 12, a Masonic lunch group that meets at noon), which gathers after lodge meetings to keep the party going. The Downtown Masonic Lodge No. 859 adjourns to Invention, one of the oldest bars in Los Angeles, which just happens to be on the third floor of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, where the lodge meets. San Francisco’s Logos Lodge No. 861 has its own special punch recipe that members partake of following lodge business.

And then there are many examples of top-drawer dinners (with top-shelf drinks) that go above and beyond these casual après-lodge gatherings, like the blowout seven-course St. John the Baptist Feast held each summer at Conejo Valley No. 807. At McColm’s Novus Veteris, members hold a quarterly “convenus,” where they wear tux and tails and eat by candlelight. “It hearkens back to an older time—a bygone era of old Masons when they wore that sort of thing,” he says. Such hat-tips to the past help connect the Masons of today to the festive practices of yore. In fact, in 2014, Grand Lodge issued guidelines to help lodges “experience our heritage by temporarily returning to the days of old” by re-creating schematics from 18th century “table lodges.” In these early gatherings, members sat around a horseshoe-shaped table with the master at the head as they wined and dined. The meal would pause when the senior steward called the brothers to “labor,” to observe the degree work. During a break or at the degree’s conclusion, the meal would resume with the junior warden calling the lodge back to refreshment.

Another example of Masonry’s formal side can be seen in opulent festive boards like the one at Anchor Bell No. 868 in Los Angeles, where reveling members in black tie sing the lodge’s own sea shanty and drink rum punch. It’s also seen at Prometheus No. 851, whose version of a festive board is a white-tie event held at the University Club, a jaw-dropping two-story brick Victorian mansion atop San Francisco’s tony Nob Hill. As befits such a setting, the members of Prometheus take their postprandial in style, with single malts and bottles of Napa and Sonoma wine poured freely.

Just don’t call the Masons a drinking club. Since the brotherhood was officially formed in 1717, when a handful of lodges joined together as the Grand Lodge of England inside the Goose and Gridiron tavern in St. Paul’s churchyard, Masons have had a fraught relationship with alcohol. Even by the standards of early-18th-century London, those lodges were known for their fondness for drink. (A famous satirical engraving from 1736 by William Hogarth, a Freemason, depicts a debauched street scene featuring a pair of Masonic officers staggering out of a pub.) Right or wrong, a boozy reputation took hold.

As a result, the fraternity has since held a firm line on alcohol in the lodge.

In fact, drinking is prohibited at lodge meetings and in lodge rooms. Until 1989, California Masonic temples weren’t allowed to serve booze in their dining halls. Other stipulations remain: No lodge funds can be used to buy alcohol, though it can be bought and donated by a member. That attitude is reflected in the first Masonic cardinal virtue, temperance. The idea was to prevent an overserved member from breaking his solemn oath—you know, in vino veritas. Today, temperance is as much about respecting the sanctity of the lodge as about spilling the beans.

From the beginning, that meant toeing a narrow line, as early Masonic lodges frequently met inside pubs or taverns. Those early forebearers would conduct their meetings above the bar, and then later, after wrapping up business, retire downstairs for dinner and drinks. Like most lodge activities, these moments of gastronomic gaiety worked to build Masonic brotherhood—so long as it was kept within reason.

That responsibility traditionally has fallen on the junior warden, who is charged with maintaining order while the lodge is at refreshment, and who often organizes the purchase or donation of alcohol. Lodge-minute books from the 18th century are full of examples of fines levied by the junior warden against members who “forgot themselves” and took part in less-than-stellar behavior around the table. Nowadays such fines are forbidden. If a member does overindulge, the junior warden simply pulls him aside to let him know he’s cut off for the evening. Above all, the junior warden’s roll at refreshment isn’t that of a lodge’s Officer Krupke, but to make sure that social activity—and all it encompasses— moves along swimmingly.

That isn’t just a relic of Masonry’s tippling past. It’s also a gesture to those who don’t drink. For sober brothers or members who just don’t prefer it—Ackeret, for example, eschews booze during social gatherings, preferring iced tea with a squeeze of lemon—the storied halls of Freemasonry are welcome dry spots. (Similar to Alcoholics Anonymous, Freemasonry relies on fellowship to foster growth and has no political affiliation; in fact, both groups use the equilateral triangle as an important symbol.)

One place where the craft and the bottle do meet is in the custom of offering a toast—or, as is often the case, many toasts. In the out-of-print tome A Selection of Masonic Songs, published in 1975 and full of ancient salutes to drink, the brethren would sometimes sing, “Coming, coming, coming, sir, the waiter cries, with a bowl to drown our care.” Verbal tributes vary from lodge to lodge, and they run the emotional gamut, from earnest and profound to bawdy and bold. Take for example this one from the 18th century: “Charge, Brethren! Charge your glasses to the top / My toast forbids the spilling of a drop.”

At Oakland’s Academia Lodge No. 847, the monthly festive board—called the agape—is serious business. Held inside the swank library of the Oakland Scottish Rite building, members dress in white tie and gloves, with officers wearing the gauntlet of their station on their sleeve. The recitation of toasts from memory is a highlight of the evening, says past lodge master Paul Adams. At the cue of a master of ceremonies, the toast-giver slings his napkin over his shoulder and offers his salutation, followed by the thunderous crash of drained “firing glasses”—heavy shot glasses, essentially—being thumped on the table.

The act of toasting provides a way for the lodge to formally—and good-naturedly—honor members, friends, and founding fathers. “There can be a toast to the country, a toast to the grand master, and a toast to the master of the lodge,” says Weiss. “There’s also a toast to absent brethren, a toast to visiting brethren, and even a toast to the ladies.” At certain kinds of gatherings, these can add up. At Adams’ Academia Lodge, for instance, there are usually seven toasts. At Conejo Valley’s annual feast there are eight. “Our members know better than to put too much in their glass,” Adams says. “Because if you drink seven whiskey shots—it’s not good.”

So crucial is toasting to the Masonic experience that drinking vessels have become a part of many lodges’ lore. Some halls still possess ornate Masonic punch bowls, made of ceramic or pewter and embossed with Masonic symbols and emblems. Other lodges, like McColm’s Roseville group, use metal tankards, while the aforementioned Prometheus Lodge feast in San Francisco involves passing around a “tig”—a three-handed sterling silver loving cup, which each brother holds and then is made to answer a question posed by the master of ceremonies, intended to prompt deep self-reflection.

Many other lodges have special firing glasses, or cannons, used to punctuate a speech or toast.

For all the many, many rituals centered on these time-honored traditions, Masons point out that drinking itself plays only a supporting role in times of refreshment. Instead, it’s the one-on-one connection men experience at these lively moments of leisure that keeps the tradition alive. It affords members new and old a chance to enjoy the social side of Freemasonry while meeting each other on the level. Being at refreshment, according to Daza-Ritchie, shows that Freemasonry “isn’t all drudgery or old guys in suits, but interesting people who really enjoy one another’s company.”

Weiss, who has played emcee for Conejo Valley’s St. John’s Day Feast for most of the past 25 years, joined the Freemasons in part because he had relatives in it. “But what got me hooked, and kept me coming back for more, were the centuries of history and the character of the individuals I met along the way,” he says. Surely that’s worth raising a glass to.

PHOTOGRAPHY CREDIT:

Nader Khouri

Courtesy of the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum

More from this issue:

Pub Crawling Through History

A time-traveling, continent-hopping pub crawl of the fraternity’s most important watering holes.