"SOMETHING MODERN SOCIETY ISn'T FULFILLING": ESoteric Origins in Freemasonry

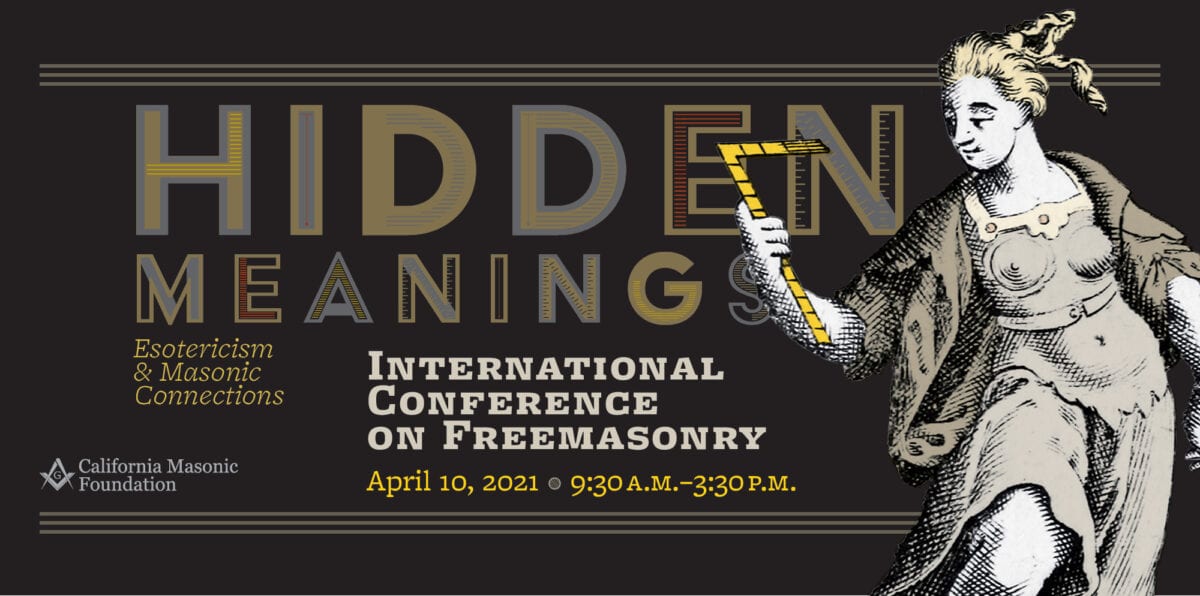

Ninth annual International Conference on Freemasonry at UCLA will explore the Masonic quest for secret knowledge.

By Ian Stewart

Susan Sommers jokes that as daughter of the Midwest, she was exposed to Masonry early. “Every rock you turned over, two or three Freemasons would pop out,” she says. That familiarity with the fraternity eventually came to influence her scholarly work as a historian of 18th century British politics—a field practically awash in members of fraternal orders. And despite what she knew about the strong connection members have with Masonry, Sommers was surprised by the lack of recognition historians had paid to those Masonic bonds. “It just doesn’t show up in the literature,” she says, “but we know that it’s the most important thing for understanding who these men were—who their friends were, what their priorities were.”

The result has been that Sommers has developed into one of the leading researchers on Masonic history—and for the past two years, organizer of the International Conference on Freemasonry, hosted by the Grand Lodge of California.

This year’s conference, being held April 18, is titled Hidden Meanings: Esotericism and Masonic Connections and centered around the eternal quest for secret knowledge that has for centuries held a special appeal for many members of the fraternity. Here, California Freemason speaks with Sommers, a professor of History at St. Vincent College in Pennsylvania and author of The Siblys of London: A Family on the Esoteric Fringes of Georgian England (2018, Oxford University Press) and many other books, about this year’s event.

California Freemason: This year’s conference is primarily concerned with esotericism. Has that always been the defining characteristic of Masonry—what stood it apart from other fraternal orders?

Susan Sommers: Esotericism isn’t something that appeals to all Masons and it never has been. But it’s certainly there and it’s a strong current running through the 18th century and on through the present. So on the one hand, we’re going to be looking at how that came to be and how various individuals experienced it; and on the other hand we have speakers like Ric Berman who say, ‘No, it just got invented and thrown in there because it was sexy.’

CFM: Your paper follows a doctor and Mason who was interested in what we’d call the occult. Is this part of the same interest that was so prevalent in turn-of-the-20th century Britain in people like Arthur Conan Doyle and William Butler Yeats?

S.S.: Yes, although they come a century later. It’s an early romantic impulse, the beginnings of that movement. These are people who said, ‘Newtonian science is all well and good, but it doesn’t speak to my soul.’ You can see the esoteric tradition in Freemasonry in the 18th century as a connection between the late Renaissance and their interests in the occult, or hidden knowledge—the whole Rosicrucian tradition. There’s this sense that there’s something modern society isn’t fulfilling.

CFM: Today, many people think about Masonry as a means for making friends, giving back to your community, and becoming a better man; others come for the secret-knowledge part. Has that always been the case?

S.S.: Yes, that’s not new. But if you don’t know about Masonic history, you wouldn’t know it’s not new. James Anderson, who wrote the first Book of Constitution in 1723, was also looking for the origins of the great religion of the world—the one religion he believed we all followed at one time. So he certainly was part of this school of thought that there’s ancient, valuable information we’ve lost and we need to regain.

CFM: What do you see as the benefits today in learning about the origins of this strain of thought?

S.S.: There’s always been this temptation to see those on the other side as being mistaken about the nature of the organization—that they don’t understand what it really means to be a Mason. I think it strengthens the fraternity to recognize that if history makes something legitimate, then both aspects of the fraternity—the fraternal part and the esoteric part—are legitimate. We can see people being interested in charity and sociability, and people interested in lost or hidden knowledge all the way back to the beginning. Whenever that was.

Register now for the International Conference on Freemasonry at UCLA.