Member Profile: Seb Badoyan

From Beirut to the San Gabriel Valley, Seb Badoyan has made a point of giving back to others.

By Nancy Stearns Theiss, PhD

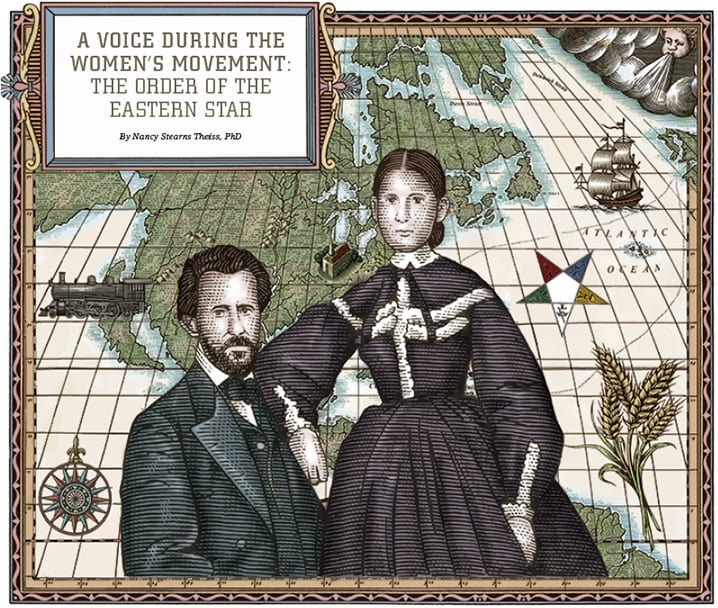

The years leading up to 1851, when Rob Morris penned the degrees for the Order of the Eastern Star (OES), were a pivotal time for women’s rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was organizing the first women’s rights convention in July 1848, and produced the Declaration of Sentiments. The opening of the American frontier provided new land and resources for exploitation and profit, and the railroad and steamboats began distributing goods far and wide. As manufactured goods started to supplant handmade and homespun items, women were afforded some “leisure time,” once a foreign concept, particularly for women in rural and frontier areas. Women were also involved in anti-slavery groups and abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass, supported women’s rights. And although both movements gained momentum and support, their issues were not the same and required different directions.

Throughout his formative years, Morris was sympathetic to women and their contributions to society. He witnessed his own mother’s hard work in raising a family without support when she separated from Morris’ father. (She remarried in later years.) His mother valued education and made sure her children, Rob, Charlotte, and John were educated.

As a young man of 18, Morris left his Taunton, Massachusetts home to explore and experience the new American frontier. He taught at an academy near Memphis, and was inducted into Freemasonry at Gathright Lodge No. 33 in Oxford, Mississippi, on March 5, 1846. This was to become a milestone in his life that changed his career and interests. He quit his teaching job and started selling magazine and newspaper subscriptions across Mississippi and Tennessee, as well as giving lectures on Freemasonry at churches and lodges.

Morris’s vision for the Order of the Eastern Star allowed, in a conservative fashion, for women to belong to an organization with traditional and respected history, while giving them a voice.

As he learned more about Masonry, Morris saw the introduction of women into Masonic organizations as a way to improve it. Morris had visited many Masonic lodges and found that often they were in disrepair and members were not adhering closely to Masonic rituals. He thought women would help “clean up” lodges and bring a higher standard of protocol. In addition, Freemasons “inspire philanthropy” and Morris felt women were more empathetic than men to the causes of widows and destitute children.

Perhaps the most important part of Morris’s vision for the Eastern Star was not just to strengthen lodges, but to broaden the opportunities for women in the workforce, as he stated:

And there is another practical result of the Eastern Star movement, the credit of which I am in no wise inclined to give to others; this is the broader opening that is offered to females for self-support. The deadly needle, the unwomanly washtub, the unwholesome country school, the sinew-wearying kitchen, are not now the only fields on which women, old and young, who are wrestling with the perplexities of human life, can win bread. Thousands and tens of thousands of places, cleanly, womanly, easy, and fairly profitable, have been opened to them since the story of the “Five Heroines of the Eastern Star” was first disseminated in 1850. In almost every post office and courthouse throughout the lands—in a great number of banks and libraries—at the desk of cashiers of mercantile houses—behind counters—but the catalogue need not be extended. Long as it is, it is daily lengthening, and every year the salaries of women are brought more nearly to those of men, as it is found they are equally accurate and expert in business, and that the defalcations, forgeries, and general rascalities with which our morning papers are defiled are commonly the work of men, rarely of women. (Jean M’Kee Kenaston, 1917)

And while Morris was by no means the first to introduce adoptive Masonry for women, he may well have been one of the most successful. The influence of female masonry and various degrees that had been established before Morris’ development of the Eastern Star Degrees certainly influenced Morris, but the manner and style is “distinctly original” and from Morris’ hand. According to his biographer, Dr. Thomas R. Austin in A Well Spent Life (1876):

“One thing is known to all readers of Masonic literature in America: that numerous degrees in which both sexes are admitted were in use among us long before Dr. Morris’ day. The Heroine of Jericho, The Secret Monitor, The Masons Daughter, The Good Samaritan, The Ark and Dove, and others. Dr. Morris merely used his privilege as a Masonic teacher to invent and put into use other degrees of the same class but far superior in merit”.

The OES gave women a platform of visibility at a time when women had little opportunity in business, government, and education. It embodied the power of women as a force to make positive changes in their lives specifically, and for women generally.

Morris was intuitive for the times and his efforts reflected the major initiatives of the objectives of the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments. Morris’s vision for the Order of the Eastern Star allowed, in a conservative fashion, for women to belong to an organization with traditional and respected history, while giving them a voice. Women could use the local Masonic lodge to socialize, organize, and provide charity for the community outside of their church and home; a great asset particularly in more isolated, rural areas. The OES also connected women to the larger framework of a Masonic fraternity that had already established itself within a national and international network.

On May 4, 1851, Rob wrote his wife Charlotte from Trenton, Tennessee in Gibson County. In this letter, he mentioned that he conferred degrees on more than 50 ladies and would do the same for her when he returned home. Of course, Morris’s enthusiasm for the Order of the Eastern Star was met with resistance by those who felt women had no place in Masonry and he was often dubbed “The Petticoat Mason.” Morris stated: “Letters were written to me, some signed, some anonymous, warning me that I was periling my own Masonic connections in the advocacy of this scheme.” But these threats were of no avail.

The Order of the Eastern Star was the first membership organization in the United States that gave women a voice on a national scale. This was an extraordinary accomplishment given the distance separating the frontier communities from the more populated areas in the United States. The OES gave women a platform of visibility at a time when women had little opportunity in business, government, and education. It embodied the power of women as a force to make positive changes in their lives specifically, and for women generally. It stood as a beacon for women to get involved locally as well as nationally and internationally to improve society.

Nancy Stearns Theiss, PhD. grew up in LaGrange, not far from the Morris home. She is the executive director of the Oldham County Historical Society. Her book “A Place in the Lodge: Dr. Rob Morris, Freemasonry and the Order of the Eastern Star” [2018] is available from Westphalia Press.

PHOTO CREDIT: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd and Almay Stock Photo

From Beirut to the San Gabriel Valley, Seb Badoyan has made a point of giving back to others.

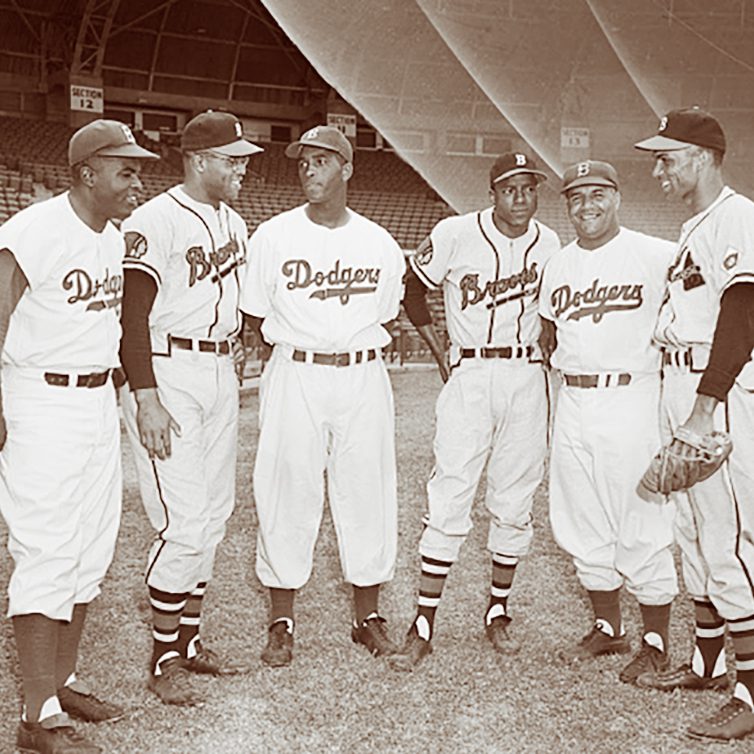

A new exhibition in San Diego spotlights Negro League pioneers, thanks to a gift from the Masons of California.

At the Masonic Family Park in Washington State, a Masonic campsite is a respite for the fraternal sojourner.