STRIKING GOLD

Up and down California’s Gold Country, lodges are tapping into a unique history to chart their way into the future.

By Ian A. Stewart

Jon Waller didn’t know much about the old Masonic lodge hall in Grass Valley when he and his wife relocated to the area from Vallejo in 2018. But he was curious.

Like a growing number of Bay Area professionals, Waller, an information technology worker, moved to the Sierra foothills in search of space, quiet, and scenery. “In the evenings, we can sit out and watch the stars,” he explains from his home in Browns Valley. “I love this area, the rustic outlook. I wanted to get away from the day-to-day grind of city living.”

The move also presented Waller with an opportunity to investigate Masonry, which he’d always harbored a curiosity about but had never acted on. What better way to integrate himself into a new community than to meet members at lodge. Making friends and getting to know his new neighbors might help him establish a foothold in the region, a connection to his new town. He petitioned to join the lodge in Grass Valley, about 20 miles away, met several members, and soon received his first degree. He also started to learn about the history of Madison Lodge No. 23, which was founded in 1851, part of the first wave of Gold Rush–era lodges chartered through the Grand Lodge of California. Portraits of lodge masters going back decades illuminated an unbroken history that stretched to the very founding of the state of California. “I started to appreciate the lineage of that,” Waller says. “To imagine the stories that have gone on here. It opens your mind to the history. It opens up your imagination.”

Before long, Waller began to understand that he’d tapped into more than just a group of friendly neighbors.

A Profound Connection

“This community is very tied to its history, very proud of it,” says Sean Metroka, master of Nevada No. 13 in Nevada City. The lodge was first chartered in 1850, making it the eighth-oldest still-operating lodge in the state. “For us, it’s really important to be able to say that we were here when it started—that our members were leaders in this community when it started and continue to be even today.”

With John E. Trauner, a second-generation member of Madison Lodge No. 23, now installed as grand master of California, the attention of the fraternity has turned to the Gold Country, where small-town and rural lodges with histories more than a century and a half old are hoping to tap into what in many cases is a regional revival spurred by people like Waller. From Sierra City in the north to Mariposa in the south along Highway 49, the so-called Golden Chain Highway, these small lodges are adapting to changing demographics and, in some cases, existential challenges. As they seek a path forward, Trauner is committed to shining a light on the special place these lodges hold within the fraternity.

In order to look toward the future, however, it’s instructive to first look to the past. Indeed, the history of the Gold Rush and the founding of the Grand Lodge are practically inseparable. The incredible flood of miners—vast numbers of whom were Masons from other states, many carrying charters from places like Wisconsin and Maryland and all points between—led to the almost overnight founding of scores of ad hoc lodges from the Sierra to San Francisco. In fact, of the first 101 lodges chartered by the Grand Lodge of California between 1850 and 1856, an astonishing 54 were situated in Sacramento and the counties making up the 150-mile Mother Lode vein. For decades, lodges in Nevada City and Grass Valley competed with San Francisco’s California Lodge No. 1 for the title of the largest in the state. That frenzy of Masonic activity produced countless politicians, businessmen, and leaders who helped shape the state of California: Nine of the 48 delegates to sign the state constitution were Masons. So too were Gold Country industrialists like James Graham Fair, the railroad tycoon and former member of Nevada No. 13; Griffith J. Griffith, of Penryhn No. 258, for whom Los Angeles’ famous park is named; and Albert Gladding, president of the Gladding McBean tile company and a member of Gold Hill No. 32.

“This community is very tied to its history, very proud of it.”

—Sean Metroka

Master, Nevada No. 13

Many of those early Masonic outposts went under as quickly as they’d popped up. By one count, 60 percent of the Gold Rush lodges had shuttered or been consolidated by the time of the Civil War. These live on in Masonic history as little more than curiosities, in places with names like Chinese Camp (Lodge No. 62), Michigan City (No. 47), Wisconsin Hill (No. 74), and Don Pedro’s Bar (No. 82). But a great many pressed on, carrying with them the artifacts, history, and stories collected over a century and a half.

These lodges are deeply rooted in place, and they offer a direct lineage back to the founders of the state and the pioneer spirit that animated them. As these communities have changed over time, so too have the lodges that call them home. Mining officially went under in the 1950s, and timber—the Gold Country’s other main industry—has slowed to a crawl over the past 20 years. In their place, tourism has become the region’s main economic driver, and in recent years a flurry of restaurants, hotels, and outdoor sporting enterprises catering to weekenders have reshaped towns up and down Highway 49. As the area once again finds itself in the midst of change, so do its lodges.

A Golden Opportunity

Grass Valley today is in many ways hardly recognizable. While the covered sidewalks and Gold Rush aesthetics of the town are straight out of the 1850s, the downtown is practically abuzz with tasting rooms, art galleries, and trendy boutiques. It’s the same story in places like Nevada City, Sutter Creek, and Sonora. In each case, an influx of new faces, many decamping from the Bay Area or Los Angeles, have discovered the small-town charms and comfort that brought so many people to the foothills in the first place.

While it isn’t quite a second gold rush, this flood of new energy presents an incredible potential for Masonic revival in Gold Country. As more and more people look to the country appeal of the Sierra foothills, the Masonic lodge is well positioned to offer these newcomers a profound connection to the local community, history, and a path to self-discovery.

It’s a story that’s already playing out in lodges like Auburn’s Eureka No. 16. There, Master Rick Hodkin explains, members have made a point of welcoming initiates and prospects, many of whom are new to the area or who commute for work to Sacramento, with opportunities for fellowship—whether through a brewery night or a tour of the lodge hall. The result has been a surge in interest, especially with younger members. Even among those without deep roots in the area, questions invariably turn to local history—something Gold Country lodges offer in spades. “Whenever we do tours, we show people the lodge minutes from 1851, show them the original Bible, the original furniture,” Hodkin says. “We have the portraits of our founding members”—people like Lisbon Applegate, namesake of the township just outside Auburn. “These people really shaped our area.”

For those newly arrived in town, the ability to tap into a community with roots going so far back is a powerful force. It’s also something worth preserving. “What these old lodges give us is a connection to that past,” Metroka says. “If these disappear one by one, we lose that connection.”

Laying the Groundwork

Of course, maintaining vibrant lodges, each with its own ever-changing character, in towns that have grown and contracted over time has not always been easy. Gold Country Masons have endured more than their fair share of fires, dissolutions, and consolidations over the years, and they often held out with just a few dozen members on their rolls. Still, many members travel an hour or more to attend meetings in remote towns like Sierra City, Knight’s Ferry, and Colfax.

That’s why ensuring the continued viability of Gold Country lodges requires not only new arrivals to the region, but also reactivating those already within the fraternity. That’s the idea behind a two-pronged strategy Grand Master Trauner is implementing, aimed at supporting Gold Country lodges in 2020 and beyond.

The first initiative is a program of restoration whereby suspended members can be welcomed back into the fraternity. In all, there are close to 40,000 members statewide suspended for nonpayment of dues. Outreach efforts have shown that in the great majority of cases, members who drift away from the fraternity do so for trivial reasons—a change of address, a missed payment, or simply the demands of a busy schedule. These tend to be members who still feel strongly about the fraternity and would likely rejoin if barriers to reentry were removed.

Under Trauner’s strategy, lodges would have the option of inviting suspended members back into the fold in good standing for a simple $100 flat fee. Similar efforts within the Scottish Rite and Shrine were able to restore some 10 percent of suspended members; even a fraction of that would have an enormous impact on the state fraternity, particularly in the Gold Country, where newly restored members would inject much-needed fresh blood, ideas, and leadership potential.

The second arm of the plan is the creation of a sister-lodge program that would pair rural lodges with an urban sibling in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, or San Diego. Although the sibling arrangement would be a nonbinding resolution, the aim is to cultivate a shared exchange of ideas and inspiration. Lodges could travel to visit one another, help confer degrees, and attend special events and celebrations, all the while exchanging valuable information and best practices related to fundraising, community service, and member outreach. In addition, renovations are planned in 2020 to the historic Quitman Lodge Hall, inside Malakoff Diggings State Park in North Bloomfield. The circa-1880s facsimile hall includes period-appropriate furnishings and decorations, and together with the historic Columbia Masonic Hall outside Sonora represents two stunning and historically fascinating locations for California lodges to hold special degrees and events in.

Lastly, the 2020 annual symposium held in San Francisco and Long Beach will be dedicated to Masons of the Mother Lode—a unique opportunity to introduce the history of the region to a statewide audience.

Freemasonry is and will continue to be an integral feature of community life in the Gold Country in the years to come. By supporting its lodges today, the fraternity is helping position them to carry the tradition forward for future generations.

The Answer Is Within

Gold Country lodges are, in many ways, unlike those anywhere else in the state. Beyond the unique portals to history they offer, the foothills lodges are perhaps more closely connected to the character of their communities than any others. Oftentimes, a visitor can spot it immediately: At Drytown No. 174, in Plymouth, members show up to lodge in their take on “Drytown formalwear”—Stetson hat, black leather vest, and cowboy boots. At Oak Summit No. 112, members created past master’s jewels out of gold dust they mined themselves. In Hornitos, members pay tribute to a square-dance-loving past master by wearing western-style neckties and dress shirts. “The lodges around here,” Argonaut No. 8 Master Steve Rhoades says before trailing off with a laugh, “they’re eccentric.”

And yet that’s precisely what draws members to them— and why they represent such an important part of the state fraternity. For lodges to grow and thrive doesn’t require turning away from their rustic allure; they need only welcome new faces and ideas. That’s the common theme that emerges among the Gold Country’s most successful lodges. “I like to stress that yes, we have a clique in our lodge,” says Bill Brewer, longtime secretary of Drytown No. 174 and a 50-year Mason. “The difference is that here, there’s only one clique, and everybody belongs to it.”

That’s a refrain that echoes what others across the fraternity say is the key to developing a rich and evolving lodge life. “The second I walked in, it felt like home,” says Hodkin of Eureka No. 16, which he joined in 2014. “That’s the number one thing people tell us about our lodge—that it’s welcoming.”

Metroka, master of Nevada No. 13, points out that of the three officers being installed at his lodge this year, two are affiliates who only recently moved to town. Embracing new members has been important to restocking the leadership line. “The thing we seem to be hitting on that keeps us strong is our friendliness,” he says. “We welcome people when they show up, and we encourage them to show up.”

Waller has felt that at Madison No. 23. “I was a little apprehensive at first, a little out of my element,” he says.

“That's the number one thing people tell us about our lodge—that it's welcoming

—Rick Hodkin

Master, Eureka No. 16

“We’d only recently moved up and were just barely getting to know the few folks around our town. And then to go to into a lodge and try to fit in and become a member?”

His fears were assuaged almost instantly. “The thing that struck me was their openness,” he says. “They took me in with open arms and told me to stick with the process. Once I was there, it was like, yeah, these are good guys. They care about you. This is only the beginning, but I can already see friendships growing and getting deeper.”

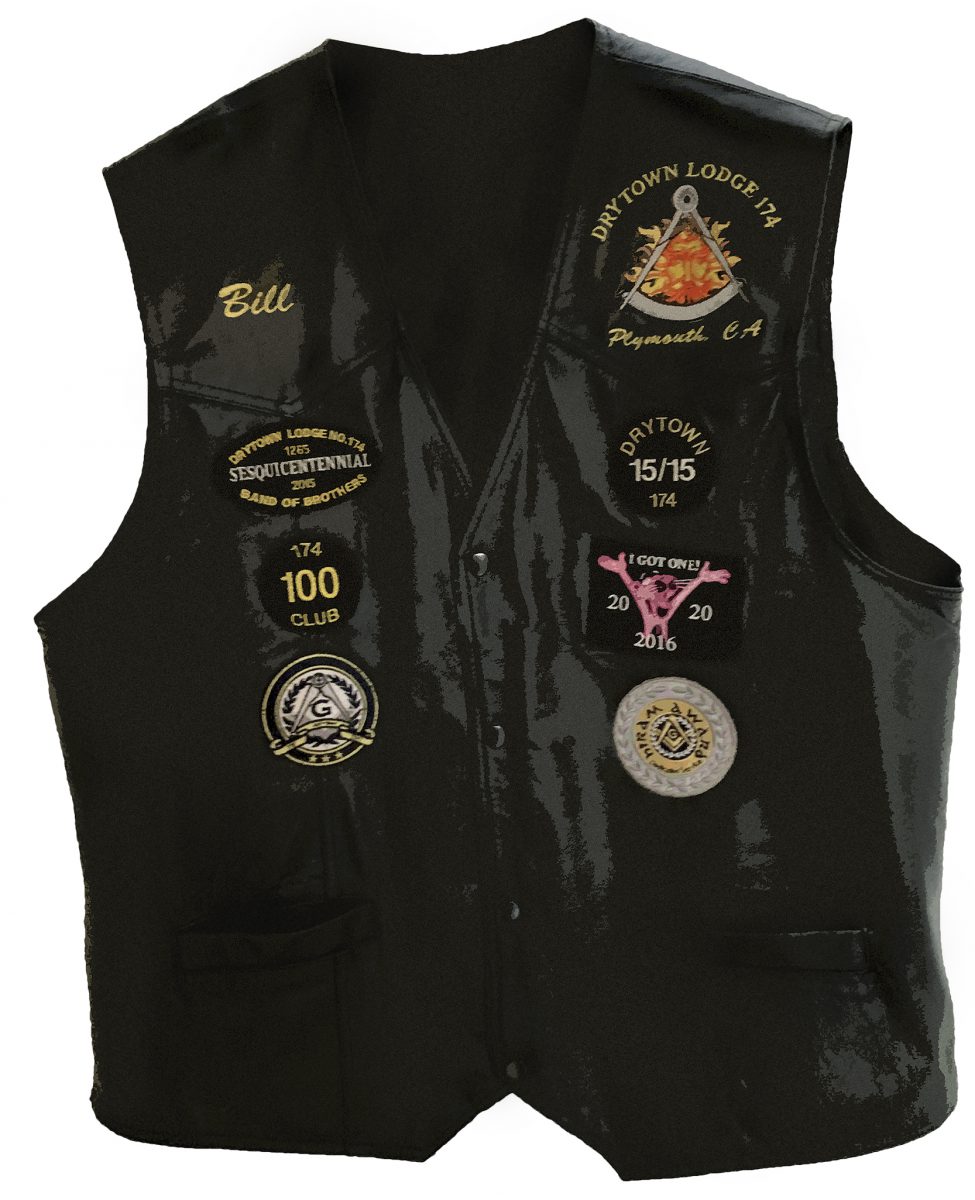

BADGES OF HONOR

Past Master Bill Brewer is designing a new patch. It’ll be red, shaped like a cowboy hat, and it’ll help pay for a dining room renovation. At Drytown Lodge No. 174 in Plymouth, that’s not so strange, because for every fundraising drive or anniversary celebration, there tends to be a new patch, to be worn with pride on members’ black leather vests. Here, Brewer gives us the story behind his ever-growing collection.

Second from top left going down:

- Drytown No. 174 celebrated its sesquicentennial in 2015, an event commemorated with a patch reading “Band of Brothers.” Drytown is one of the few Gold Country lodges never to have consolidated with another lodge, although nearby Tyro No. 73 surrendered its charter in 1859.

- The 100 Club patch acknowledges members who donated $100 or more to a fundraising drive held in 2014. Ever generous, in both 2014 and 2015, Drytown No. 174 was recognized by Grand Lodge for 100 percent officer giving.

- Another anniversary patch, this one commemorating 300 years of Freemasonry worldwide, celebrated in 2017.

- The “15/15” patch was thought up in 2015 by Past Master Dusty Deryck with a goal of adding 15 new members to the rolls. Membership in the lodge jumped from 39 in 2014 to 71 by the end of 2016.

- “I Got One!” exclaims the Pink Panther above the numbers 20/20, the current membership drive which aims to add 20 new members to the lodge by 2020.

- Finally, the Hiram Award, which Brewer received in 2015 for his long service to the lodge.

Oldies But Goodies

It’s been more than 150 years, but many of the first wave of Gold Rush–era lodges along Highway 49 are still going strong. Here, a slightly-more-than-sesquicentennial update on California’s oldest mining-town Masons.

Argonaut No. 8

Then: A product of the first Annual Communication of the Grand Lodge of California in 1850, Lodge No. 8—then known as Tuolumne Lodge—produced two early grand masters: Charles Radcliff (1853) and William Wilson Traylor (1879).

Now: A series of consolidations, most recently with Ophir-Bear Mountain No. 33 in 2016, means that as of this summer, Argonaut No. 8 alternates meetings between the circa-1874 Masonic Temple in Sonora and the 1902 Masonic Hall in Murphys.

Nevada No. 13

Then: Among the original lodges granted charters in California, Nevada No. 13 during the late 19th century jockeyed with California Lodge No. 1 as the biggest in the state—up until the demise of the mining industry in the mid-20th century.

Now: One of the most civically engaged lodges in the state, Nevada No. 13 sponsors Nevada City’s annual Constitution Day Parade each September, the largest such celebration in the west.

Eureka No. 16

Then: Originally granted a dispensation in May 1851 near Michigan Bluff, by the fall of that year diggings dried and the camp went bust. Members pulled up stakes and relocated west to Auburn, where Eureka received its charter in 1852.

Now: As of a few years ago, Eureka now follows many customs of traditional observance lodges including weekly ritual meetings, reciting long-form proficiency lectures, and instituting a six-month minimum for new applications—the result of which has been a surge in interest in the craft.

Mountain Range No. 18

Then: Downieville’s Mountain Shade Lodge No. 18 was home base for William “Bull” Meek, the legendary stagecoach driver and Wells Fargo agent of the Sierra Nevada.

Now: Having absorbed Gravel Range Lodge No. 59 and Forest Lodge No. 66, the consolidated Mountain Range No. 18 has steadily migrated south, first from Downieville to Camptonville, and then, in 2016, to Nevada City, where the daylight lodge shares space with Nevada No. 13.

Madison No. 23

Then: For many years around the turn of the century, Madison was the largest of Nevada County’s chartered lodges, which at that point numbered 13. But it wasn’t until 1926 that it produced its first grand master, George Louis Jones, who also served as a justice of the Superior Court of Nevada County.

Now: Nearly a century later, Madison is producing its second grand master in John E. Trauner, of Rough and Ready, who like his predecessor has a background in criminal justice—in Trauner’s case, as undersheriff of Nevada County.

PHOTO CREDIT:

Gordon Lazzarone

California Office of Historic Preservation

Colby Barrett

Bill Brewer

Alvis Hendley

Ian A. Stewart

Library of Congress

Nevada City Chamber of Commerce

Alvis Hendley

Visit El Dorado

More from this issue:

The Sun, the Moon, and the Master

Lunar imagery has long shined in the Masonic lodge room, literally and symbolically.