Playing a Vintage Masonic Board Game

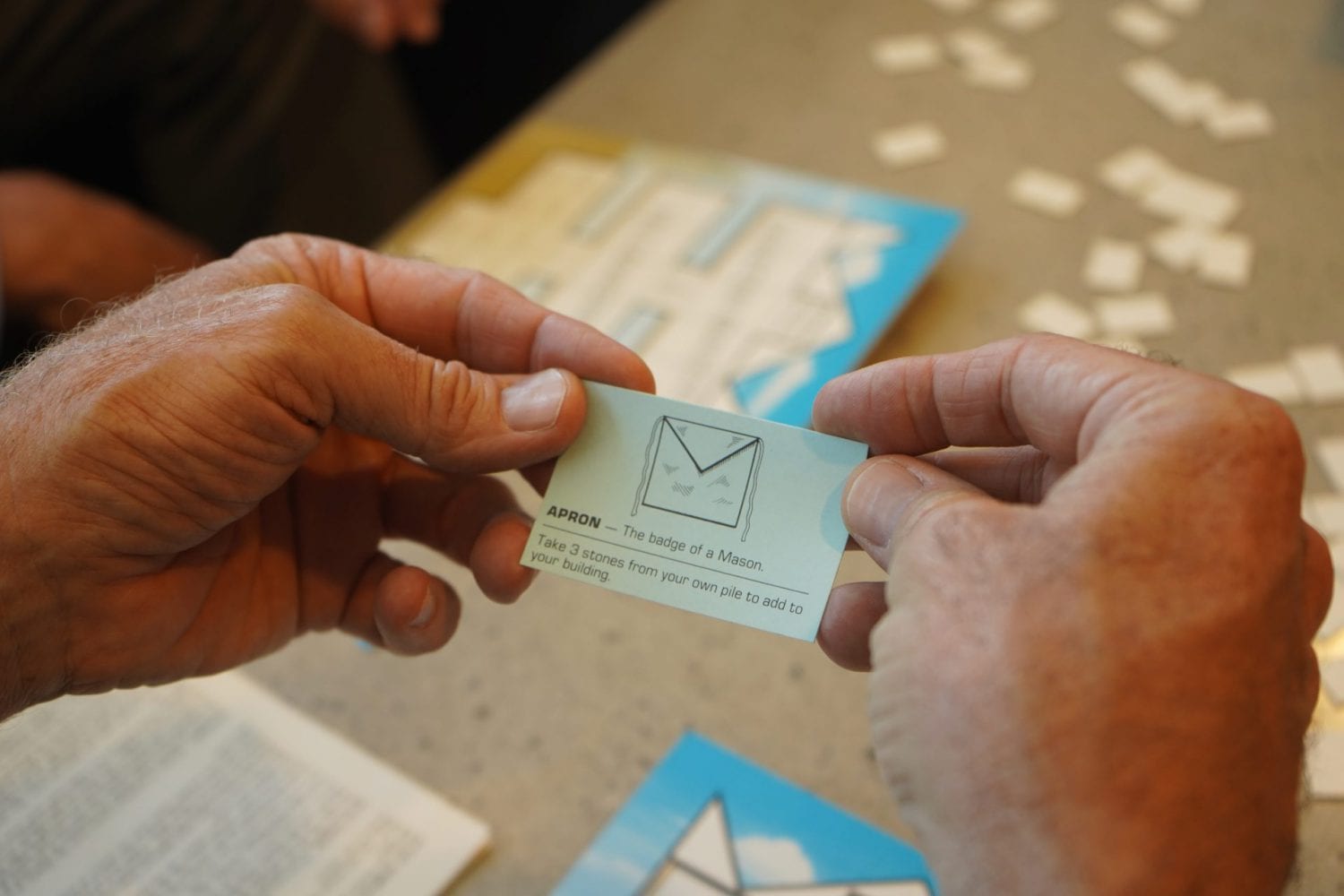

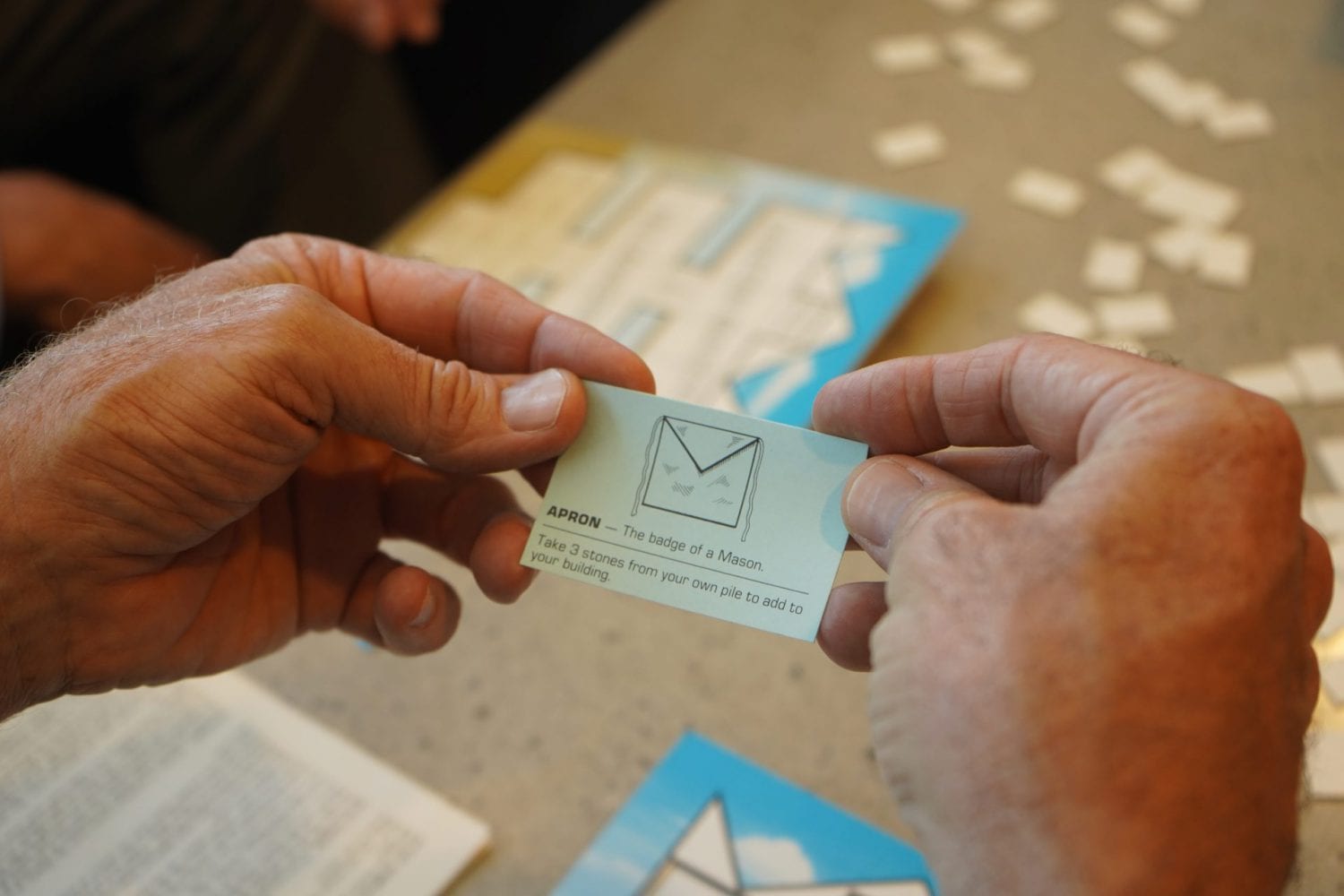

Reviewing the 40-year-old Masonic-inspired board game “BUILD.” Can Freemasonry stand up to the Monopoly treatment?

By John L. Cooper III, Past Grand Master

There’s a curious and in many cases beautiful relic in many of our lodge closets that some members have begun pulling out lately and dusting off: wall charts.

Wall charts have a long and colorful history within the craft, and one that only lately is being revived in California. Once used to help guide and illustrate degree lectures, these symbolic guides were at one time banned by Grand Lodge for revealing too much about the secret degrees. That prohibition, thankfully, is now in the past, and interest in these historic artifacts is rising throughout the state. (For more on Logos Lodge No. 861 and their handmade floor carpet, see The Do-It-Yourself Lodge.)

As Masonic degrees developed during the first part of the 18th century, it became a custom for a past master of the lodge to deliver a lecture on the symbolism of the degree. These talks were given extemporaneously, although it’s likely that the speaker used a memorized or written outline. Over time, those outlines were standardized into the narrative lectures we use today.

The wall charts grew out of those earliest outlines. Degrees in those days were often conducted in a dining room at an inn, with tables arranged in a horseshoe, leaving a space in the center of the room for a lecturer to deliver his talk. The tiler would draw a sketch on the floor with black charcoal and white chalk, and sometimes fill in those outlines with a fine powdered clay. (These days, one of our lectures makes a reference to “chalk, charcoal, and clay.”) At the end of the lecture, these secrets were preserved by having an apprentice use a mop to obliterate the drawings.

Over time, lodges found a way to preserve these sketches: by drawing on the underside of the tops of tables in the lodge. These “trestleboards,” as they were called, could be reused and hidden between meetings. Freemasons still use the term “trestleboard,” but nowadays it refers to the lodge publication.

From there, floor cloths and eventually wall charts were born. Rather than drawing on a wooden tabletop, the symbols were painted on a piece of cloth—a carpet—and placed on the ground in the place of the old tiler’s sketches. These floor cloths, many of which were quite beautiful, were sometimes hung on walls during the degree ceremony. Others painted the symbols onto wooden panels, called tracing boards.

Today, that history is still in evidence in California, as we continue to use a floor cloth in the Fellow Craft degree. Many lodges still have wall charts descended from the original floor cloths that were at one time hung on the wall of the lodge.

Elsewhere, this heritage remains strong. European lodges continue to use tracing boards in their ritual, and some of them are quite beautiful, particularly the so-called Harris Boards designed by British artist John Harris in the early 19th century.

The wall chart, however, is a peculiarly American artifact. While they were originally hand-painted, by the early 19th century they were being sold by commercial fraternal supply houses, and thus became standardized. Because it was expensive to print a wall chart in color, most of them were black and white. Candidates had to sit near enough to these charts to see the symbols. In fact, we still follow the practice of a candidate being seated near the front of the lodge for lectures.

There was a further development of these wall charts in America which did not happen in Europe. At the end of the 19th century, these symbols started being painted onto glass slides and projected onto a wall using a kerosene lantern. Most of these slides were hand-colored, and some lodges still have a collection of these slides. They were eventually superseded by 35-millimeter slides and electric projectors, and later laptops and digital projectors.

Such wall charts harken back to the early days of the fraternity, when lectures were given from memory and the sketches served as a way of explaining important Masonic symbology. Today they are reminders of our heritage, and give particular meaning to the idea that a picture is worth a thousand words.

Reviewing the 40-year-old Masonic-inspired board game “BUILD.” Can Freemasonry stand up to the Monopoly treatment?

A stunning new exhibition explores the symbolism behind hand-crafted Masonic folk art.

Musician Nate Smith of Table Mountain Masonic Lodge No. 124 in Paradise, California, turns loss into inspiration—and a fresh start.