Feeling the Sun On Their Skin

From BBQs to fun-runs, brothers share their best #MasonsOutdoors snaps.

By Emily Brady

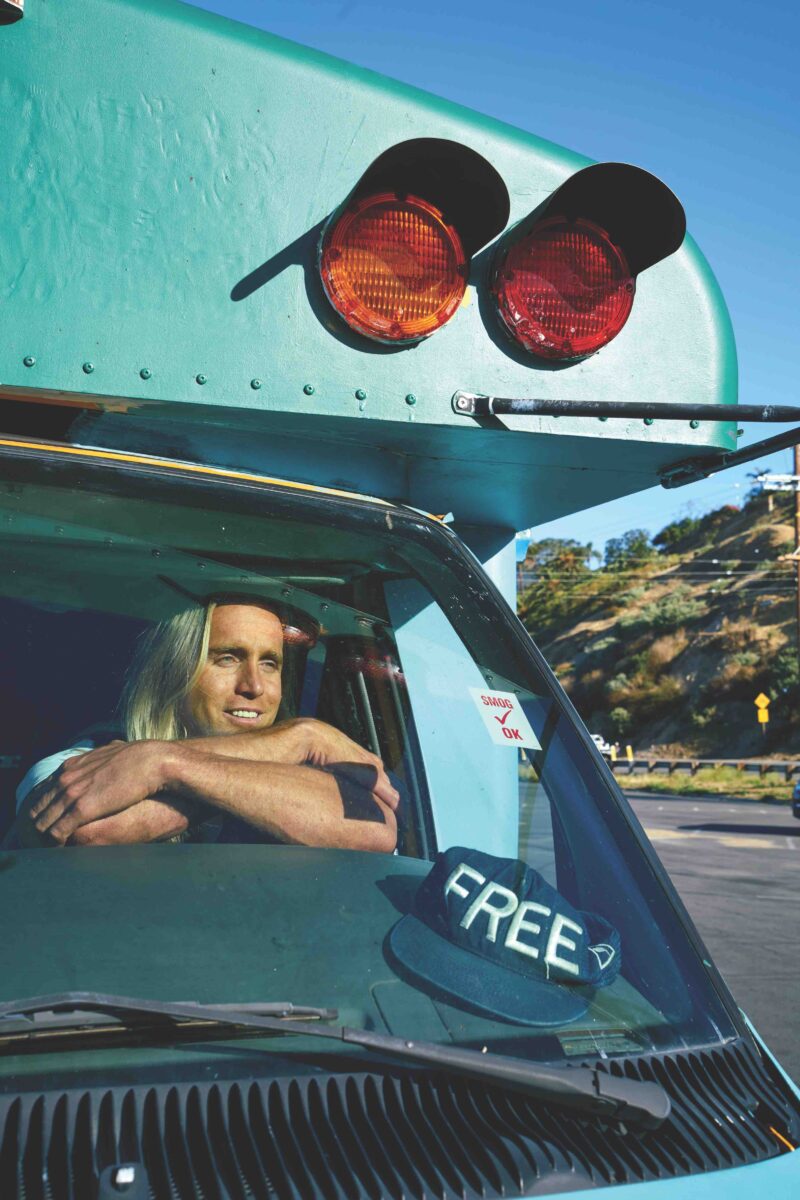

If you were to drive along the Pacific Coast Highway one day earlier this spring, you might have noticed an unusual ride parked at Zuma Beach in Malibu. With its green roof, blue front, orange bumper, and mismatched side paneling, its custom paint job is hard to miss.

The vehicle belongs to Matthew Rogers Harrison, a 37-year-old surfer and past Senior Deacon at Liberal Arts Lodge No. 677 in Los Angeles. In a previous life, the 2004 Ford Econoline 350 was a little yellow school bus. But when Harrison bought it in 2017, he had other plans for it. That involved stripping it down and turning it into something new: A “skoolie,” a sort of DIY-camper van hacked together from the remnants of an old school bus.

Harrison’s eye-catching skoolie is part of a larger trend, and one that’s been around at least since Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters toured the country in the psychedelic school bus they named Further—a journey chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. These days, however, these retrofits tend to be less counterculture and more Instagram-optimized. Those with a knack for craftsmanship or with deep pockets can install solar panels, hardwood flooring, and all kinds of additional amenities to go off the grid. In Harrison’s case, friends suggested building a high-end Hollywood tour bus or making it into a creative studio. But he had a vision: a surf caddie.

Harrison was inspired by books he read in his youth—road trip classics like On the Road and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. “I wanted to be able to explore the beaches and the Pacific Coast Highway and get into surfing more,” he says. It took him about two months to find the perfect van, but he eventually settled on one he spotted at a used truck dealership in Long Beach for $7,000 and got to work transforming it. He ripped out the seats and flooring, installed a subfloor and new hardwood vinyl flooring, kitchen cabinets, and a platform bed. Working with friends, Harrison also installed solar panels on the roof and a solar-powered generator.

By July 4, 2018, the bus—christened Almost There—was ready for its maiden voyage to the beach. And before long Harrison was pulling up at some of Southern California’s legendary breaks, from La Jolla and Moonlight State Beach to Surf Rider in Malibu, Lower Trestles in Orange County, Santa Monica State Beach, and Staircase Beach in Ventura. “A lot of people wanted to stop and talk about the bus,” he says.

As his love of surfing has grown, Harrison says he’s found parallels between being in the water—by its nature a meditative, contemplative pursuit—and the self-examination he finds in Masonry. Surfing is also a common interest among fellow members, many of whom have suggested new breaks and places to explore. Surfing, he says, is “a natural high that affects me in a very positive way and allows me to bring that energy into my life. It’s the same type of energy I feel after connecting with brothers.”

The next step, Harrison says, is marrying his twin passions: hitting the waves with his Masonic brothers. “I can’t say it enough: Everything starts to become right-sized when I’m out there in the ocean,” he says. “When there’s a common bond between people like surfing, it allows them to connect with each other and trudge forward together with higher vibrations.”

PHOTO CREDIT: Paul Smith

From BBQs to fun-runs, brothers share their best #MasonsOutdoors snaps.

Bill Prentiss learned an important lesson in business: The greatest gift is in paying it forward.

A 100-mile footrace is all in a day’s work for one ultramarathon running Mason.