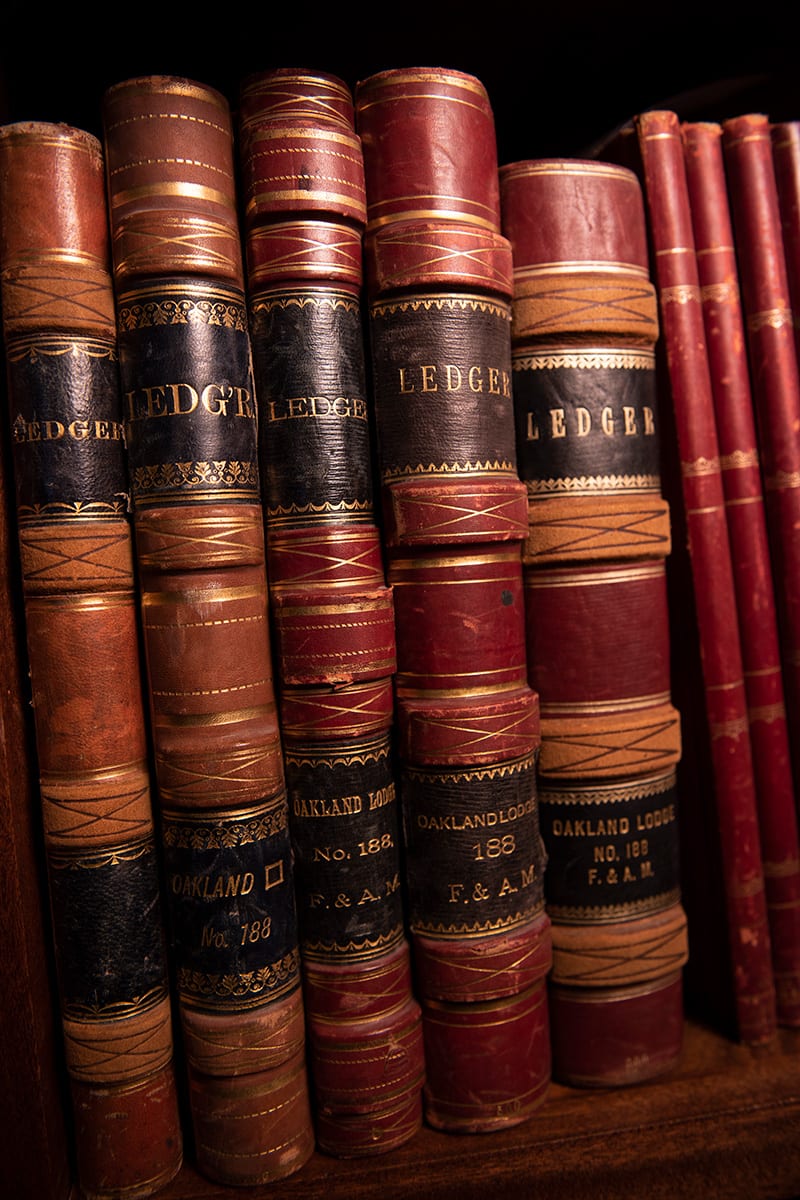

Tips For Managing Masonic Records

Lodges accumulate a mountain of records over the years, in the form of papers, books, artifacts, and photos. The sheer volume can get overwhelming.

Use these guidelines and tools to get rid of the clutter, and to take proper care of your lodge’s important records.